Critical Literature Pedagogy: teaching canonical literature for critical literacy Robert Petrone

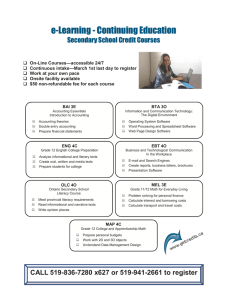

advertisement

Critical Literature Pedagogy: teaching canonical literature for critical literacy Authors: Carlin Borsheim-Black, Michael Macaluso, & Robert Petrone This is a postprint of an article that originally appeared in Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy on August 16, 2014. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy Borsheim‐Black, Carlin, Michael Macaluso, and Robert Petrone. "Critical Literature Pedagogy." Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 58, no. 2 (2014): 123-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jaal.323 Made available through Montana State University’s ScholarWorks scholarworks.montana.edu Critical Literature Pedagogy: teaching canonical literature for critical literacy Carlin Borsheim-Black: English Language and Literature, Central Maichigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan, USA Michael Macaluso: Curriculum, Intstruction, and Teacher Education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA Robert Petrone: English Education, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA This article introduces a Critical Literacy Pedagogy (CLP), a pedagogical framework for merging goals of critical literacy with canonical literature instruction. For one reason or another, certain texts (e.g., The Great Gatsby , To Kill a Mockingbird ) have become staples of the secondary literacy classroom and constitute what we refer to as the “high school canon”. Although this group of texts evolves over time and some texts are not taught in certain contexts, this corpus of literature prevails as dominant (Applebee, 1993 ; Stallworth & Gibbons, 2012 ). Oftentimes, these canonical texts perpetuate ideologies that are also dominant—about Whiteness, masculinity, heterosexuality, Christianity, and physical and mental ability, for example. Furthermore, familiar approaches to literature instruction, such as New Criticism and Reader Response, typically leave these dominant ideologies unexamined and unquestioned, thereby potentially perpetuating ideologies that privilege some and marginalize others. Critical literacy, by contrast, aims to draw attention to implicit ideologies of texts and textual practices by examining issues of power, normativity, and representation, as well as facilitating opportunities for equityoriented sociopolitical action (e.g., Comber & Simpson, 2001 ; Morrell, 2009 ; Luke, 2000 ). In addi- Critical literacy, by contrast, aims to draw attention to implicit ideologies of texts and textual practices by examining issues of power, normativity, and representation, as well as facilitating opportunities for equity- oriented sociopolitical action (e.g., Comber & Simpson,2001;Morrell,2009;Lukenaddi-tion to equipping students with skills and strategies for traditional textual analysis and production, a critical literacy approach also teaches students to read and write against texts: to identify and understand that language and texts are not neutral and always ideological. Therefore, critical literacies consist not only of academic literacies associated with reading and writing texts for traditional purposes but also practices associated with reading and writing tional curricula in school and dominant popular culture, multimedia, and other texts students encounter outside of school. Critical literacy has roots in critical social theory of the Frankfurt School (Habermas, 1975 ), which might be described as a broad, interdisciplinary, neoMarxist approach to criticism and critique of society with a commitment to social change. Critical social theory posits that all knowledge is constructed and ideological; therefore, questioning representation and normativity is part of working toward social transformation. This notion of critical social theory is distinct from critical literary theories typically associated with the study of literature, especially at the university level, such as feminist theory, deconstructionism, or post- colonial theory, while these two versions of “critical theory” grow out of different intellectual traditions, we see specific critical literary theories overlapping with and contributing to the broader notion of critical social theory undergirding this project. As such, critical literacy promotes textual engagement that emphasizes consuming (reading, listening, viewing), producing (writing, speaking, designing), and distributing texts for real- life purposes and audiences. As Luke ( 2000 ) explains, critical literacy “focuses on teaching and learning how texts work, understanding and re- mediating what texts attempt to do in the world and to people, and moving students toward active position- takings with texts to critique and reconstruct the social fields in which they live and work” (p. 453). Many critical literacy educators have developed curricula to challenge students to critique and rewrite dominant discourses, texts, and practices as they continue to develop traditional literacies (e.g., Janks, et al., 2013 ; McLaughlin and DeVoogd, 2004 ; Vasquez et al., 2013 ). Morrell ( 2004 ) describes curricula that teach traditional academic literacies related to the research paper (e.g., developing research topics) as students work to produce real texts to affect social change. Others have used media texts to teach traditional literacies (e.g., rhetorical analysis) in addition to exploring how such texts perpetuate and/or critique ideas of race, gender, and other social categories (e.g., Beach, 2006 ; Marshall & Sensoy, 2011 ). Simmons (2010), in addition to the elements of fiction, teaches The Hunger Games by connecting it to contemporary social issues like hunger and forced labor. While these examples demonstrate exciting possibilities for critical literacy instruction, there is a surprising lack of scholarship geared towards the application of critical literacy to the teaching of canonical literature specifically. Yet, we contend that it is precisely because certain texts have become canonized—upheld as having particular literary merit or cultural value—that they offer the apposite opportunity to engage students in critical literacy. A critical literacy approach to canonical literature interrupts dominant ideologies that are so often taken for granted, promoting inquiry rooted in questions such as: What and whose stories do(n’ t) these canonized texts tell? What assumptions do these texts, and by extension, secondary literature curricula, make about dominant cultural values and ideologies? Questions like these can provide the basis upon which canonical texts can be used to interrogate broader cultural assumptions, issues, and practices. While these and related questions formed the ba-sis of our own instruction of canonical literature as secondary literacy educators, we each struggled teaching with the tensions bound in the pairing of canonical literature and critical literacy because we lacked a systematic approach for merging the two. However, over time, we built on our initial attempts through reflection on our own practice, scholarly inquiry, and research into the practice of other literacy teachers (e.g., Borsheim- Black, 2012 ; Petrone & Borsheim, 2008 ; Petrone & Bullard, 2012 ; Macaluso, 2013 ). Based on this collective work, we have devel-oped a pedagogical framework—what we refer to as Critical Literature Pedagogy —to teach for the goals of critical literacy within the context of canonical literature. Critical Literature Pedagogy Critical Literature Pedagogy (CLP) weaves together two stances: reading with and against a text. Reading with a text includes familiar approaches of comprehending storylines, analyzing literary de-vices, making personal connections, understanding historical contexts, and developing thematic inter-pretations. Typically, however, literature instruc-tion stops at this stance, which, while sufficient for most traditional standards and assessments, does not call into question ideologies of texts—those values or beliefs that help to frame and form the text and our reading and teaching of it. In addition to reading with a canonical text, CLP asks students to read against it to examine how it is embedded in and shaped by ideologies. Drawing on theoretical and pedagogical traditions of critical literacy, reading againstcanonical literature challenges students to consider not only what is written in the text but also what is not written that still accounts for the way the story works, the characters function, and how readers come to know and understand the world. Thus, reading against canonical literature means reading between the lines to expose and interrupt embedded, dominant narratives, power dynamics, and perceived normalcy espoused by and hidden in the text, including its inclusion in school curricula. For example, reading against a text might include examining the norms of the historical context in which it was written or how the text has come to be canonized in secondary curricula. Hence, reading against a text is meant to help students question how and why their own beliefs, values, and assumptions are formed. Thus, CLP brings with and against stances to the following dimensions of literary study: Canonicity Contexts Literary Elements Reader Assessments While we have delineated distinct dimensions, it is important to note that these categories overlap and are constitutive with one another. For example, the category “Canonicity”—which asks students to call into question the ideologies of literacy curriculum by interrogating how and why particular texts are perpetuated as canonical and others are not—will necessarily tie in with the category “Contexts,” which recommends the use of counterstories for illuminat-ing how canonical novels often perpetuate normative power dynamics. We offer these dimensions as dis-crete entities to provide accessible entry points, not as a prescriptive guide that would constrain interpreta-tive possibilities. Moreover, although we contrast reading against and with texts, we do not actually see these two ways of reading as dichotomous. We understand reading with texts as subsumed by reading againsttexts whereby the relationship between these ways of reading text are reciprocal—learning to read withmightbe seen as necessary to being able to read against them. Also, in our own experiences, we have seen that deep thinking and engagement related to reading against texts for critical literacies lead to stronger skills related to reading with texts for academic literacies. The chart below overviews these dimensions and how they function across both with and againststances. This chart, designed for use by both teachers and students, is meant as an entry into these ideas and not meant to be exhaustive. To illustrate each dimension, we ground our explanations in examples from John Steinbeck ’ s Of Mice and Men , which prevails as one of the most commonly taught texts in secondary literacy classrooms (Applebee, 1993 ; Stotsky, 2010). Canonicity As previously discussed, secondary literature curriculum continues to be dominated by a particular group of texts. The cultural and literary value of these texts—as well as their inclusion in literature curricula—is often taken for granted. Reading witha text related to canonicity assumes that students should read a particular text precisely because it is among the most frequently taught texts. From this stance, students typically explore questions such as: Which books are in “the canon”? Why might this book be considered canonical? (See Table 1 .) Reading withSteinbeck’sOf Mice and Men [OMAM] , for example, students might explore that it is one of the most frequently taught titles, that Steinbeck was awarded Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes, and that two film versions of OMAMexist. This with exploration of the text reinforces its place in the canon, establishes a sense of the text ’ s inherent value, and perpetuates the ideology of curriculum. Readingagainst a text ’ s canonicity challenges this taken- for- grantedness by asking students to take the canon as an object of examination, much like, for example, James Loewen (2007) advocates history teachers teach students to interrogate the ideologies of history textbooks. By taking this approach, students engage in authentic disciplinary questions, and the curriculum becomes not a static entity to be under-stood, appreciated, or simply regurgitated but rather an active process of meaning making and “conversa-tion” (Applebee, 1996). Questions such as the following can be used as starting points for questioning canonicity (see also Table 1): TABLE 1 Questions to Guide Critical Literature Pedagogy Dimension of Literary Study “With” “Against” Key Ideas from CLP Canonicity Consider the merit of the book. • What is a/the canon? • What titles are included in “the canon”? • What do literary critics say about the value of this title/ author? • What awards has this title and/ or author received? • Why is it important we read this book? Challenge the text’s prominence. • What are unintended consequences of a/the canon? What does it reflect about cultural values? • What debates surround this book? • What factors contribute to a text being considered canonical? Who decides what is canonical? • What other texts written within the same historical context are not included in the curriculum? • Who benefits or gets marginalized from the inclusion of this novel? • Should we read this book? • No text is ideologically neutral. • Canonical novels—by virtue of being canonical— reinforce cultural values that should be examined and questioned. • Literary canons have historically privileged some voices and marginalized others. • How we read books matters just as much as what books are taught. Contexts Identify the book’s contexts. • What major historical movements or events took place when this book was written/takes place? • What are the familiar “stories” of this historical period? • How does the novel reflect these familiar stories? • How does the novel reflect the author’s life experiences? Identify counterstories from the book’s contexts. • How does this text perpetuate and/or subvert dominant understandings of its historical context? • What version of the historical period does this book tell? What are other versions? • How would the story be different if someone of a different race, gender, or ethnicity wrote it? • Many canonical novels reinforce dominant narratives of history. • Some canonical novels interrupt dominant narratives. • Literary canons have typically privileged White and male voices; counterstories can make dominant ideologies visible. Literary Elements Identify literary elements. • What are the major plot points of the story? • What are the major symbols of this book? • Major themes? • How are the characters developed? • How do the literary elements contribute to the theme or universality of the text? Consider embedded values or ideologies the text reproduces. • Are characters from historically marginalized populations complex or stereotypical? • Whose story is emphasized or valorized? Portrayed as a victim or hero? • How do the plot and themes support or challenge normative ways of thinking about topics being portrayed (e.g., American Dream)? How do these themes support certain belief systems, or ideas of “normal” or universal? • How do the symbols reflect particular cultural knowledge? What would someone need to know in order to understand the symbols used? • Canonical novels often represent individuals from marginalized populations as flat or “token.” • Characters from marginalized populations often play a secondary role in the plot of a novel, in support of a culturally dominant main character and hero. • Themes of canonical novels often reinforce dominant ideologies about topics like class, achievement, sexual orientation, etc. TABLE 1 Continued Dimension of Literary Study “With” “Against” Key Ideas from CLP Reader Connect text to personal experiences. • How do I relate to characters or themes on a personal level? • How does my (lack of) connection shape my reading of this novel? Consider perspectives other than your own or consider your own perspectives in a new way to examine power and privilege. • How does my identity (e.g., ability, sexual orientation, age, religion) shape my reading? • Do I relate more with characters in power or with marginalized characters? How might this positionality shape my reading of the text? • Just “relating” can undermine attempts to engage students with power and difference. • Readers from culturally dominant backgrounds often struggle to identify and question dominant ideologies because they often remain invisible to individuals in privileged positions. Assessments Standard literary analyses. • What analyses or literary criticism have been written about this book? How might I write about my interpretation of the text in relation to them? • How might I write a Reader Response, New Critical, or New Historical interpretation of this novel? Opportunities to create and distribute texts that critique normativity for real audiences.\ • How can the ideas and information developed in reading with and against canonical texts be used to inform, persuade others about oppression and injustice, particularly in my local contexts (e.g., school)? • How can I affect change based upon my critical learning? • Connect critical understandings of issues in canonical novels to similar issues relevant to other contexts. • Transfer the critical literacies used to analyze canonical novels to analyze other texts (e.g., popular culture, media). • What factors contribute to a text being con-sidered “canonical”? Who decides what is canonical? • How did this particular book become a canonical title in school curriculum? • What other books might replace or augment this book? Who benefits or gets marginalized from the inclusion of this novel? These questions are designed to demystify the canon, highlighting that what is in/excluded from the canon ought to be the subject of continuous debate. Thus, reading against canonicity emphasizes that decisions about literature selection are not politically neutral; they are made based on myriad factors, including curricular goals, personal tastes, available resources, and tradition. Considering canonicity from this stance reveals that no text is “sacred.” CLP encourages students to consider not only what literature is selected, but also what literature is not selected. That which is left out—as much as that which is left in—teaches lessons about which stories matter and what “quality” literature looks like. As students question canonicity, they might examine what other works are(n ’ t) required in their school ’ s curriculum, asking: Whose stories are most often told and whose are not? Students might also be asked to research what other texts from similar timeframes or cultural groups are unknown within their curriculum. Similarly, students can examine which texts by particular authors are canonized while others by the same authors go untaught. Readingagainst the canonicity of OMAM,teach-ers might ask why this novel was selected as opposed to others. Why not read Steinbeck ’ s other novels, especially considering many of them offer far- more scathing critiques? Or, why OMAM and not Michael Gold ’sJews Without Money or Richard Wright s’ Uncle Tom’s Children, both of which were published in the same historical context and address similar issues? This line of questioning might cultivate conversations around OMAM’s placement on the American Library Association’s list of most frequently banned titles, in addition to being one of the most frequently taught novels. How is this paradox possible? Reading against OMAM’s canonicity engages students in denaturalizing and calling into question the very curriculum they are being asked to study. Contexts Common approaches to teaching literature take into consideration historical and biographical contexts. Reading with a text in this dimension often entails asking questions such as: How does the novel reflect what was happening during the time the book is set or written? How does the novel reflect the author’s life experiences? (See also Table 1.) A typical reading with OMAM in this dimension includes considering the historical context in terms of the Great Depression. Teachers sometimes invite students to read an informational article or do online research on the Great Depression and Steinbeck’s life and may connect Steinbeck’s experiences spending time in migrant camps with his focus on migrant workers. Reading against contexts means considering what else might have been happening at the time in which the novel was written or takes place. It might also mean looking at how the text speaks with or against dominant values of the time. Both of these notions press against what might be taken as normal from the text’s contexts. Some questions that work towards this goal include (see also Table 1): • To what extent does the author contribute to counterculture movements or reinforce dominant ideologies of the time? • How might the author’s own background encourage particular interpretations of the text? How would the story be different if someone of a different background wrote it? “Literacy educators might consider how OMAM—and the secondary literature canon—contributes to heteronormativity.” To answer these questions, students need to explore not only dominant understandings of these historical contexts but also alternative, non-dominant histories, as represented, for example, by historians like Howard Zinn (1980). In some ways, this work of considering various historical contexts echoes the against approach toward canonicity, where students interrogate the recognition of texts. Helping students detect dominant ideologies can be difficult because they are written into the very fabric of our society. One way of making dominant perspectives more visible is by juxtaposing them with contrasting perspectives, or “counterstories,” which foreground voices of people from nondominant positions to challenge normative ideologies by telling a different side of the story (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001). To locate counterstories, teachers might include texts written by writers, musicians, activists, artists, or politicians who were active at that time and who represent historically marginalized perspectives. To read against contexts in a unit on OMAM, students might consider African American perspectives on the Great Depression. For example, Langston Hughes’ poem, “Let America Be America to Me,” provides a critique of the American Dream from an African American man’s perspective. Published in 1935, the poem, like OMAM, comments on social class and the myth of the American Dream; however, it opens up opportunities to consider race and power in ways OMAM does not. Of course, Langston Hughes does not represent “the” perspective of people of color; literacy educators might also include other texts about the experiences of African Americans during the Depression era, as well as integrate Mexican American, Native American, or Asian American voices. Similarly, to offer counterstories to the dominant male perspective, students could read works by or about women of the era, such as Jane Addams, Marian Anderson, Eleanor Roosevelt, Zora Neale Hurston, Mary McLeod Bethune, or Dorothea Lange. Literacy educators could take the reading of OMAM as an opportunity to consider how the text constructs dominant views about sexual orientation. Literacy educators might consider how OMAM— and the secondary literature canon—contributes to heteronormativity, the assumption that straight people are “normal” or superior to people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) (cf. Blackburn & Smith, 2010). They might also think about ways to incorporate counterstories of the Great Depression that represent perspectives of individuals who identified as LGBTQ. To do so would emphasize the typical silencing of LGBTQ voices during this era and consider how the omission of LGBTQ voices in the high school literary canon, including OMAM, contribute to the notion of heteronormativity. Examining counterstories illuminates the fact that OMAM, written by a White, straight, middleclass, English-speaking, able-bodied male author tells one version of the story of the Great Depression. Using counterstories to read against contexts, then, CLP asks students to go beyond exploring how texts merely reflect historical contexts; instead, it asks students to interrogate how a particular text contributes to the construction of dominant ideologies by marginalizing non-dominant perspectives. Literary Elements Traditional approaches to literary analysis are often informed by New Criticism, which values a close reading with attention to literary devices including character, plot, symbol, and theme. We equate this approach to reading with a canonical text; in fact, we may go so far as describing it as a canonical reading of a canonical text—exemplified by any SparkNotes guide to any canonical novel. From this perspective, a typical character analysis of OMAM would identify George as the protagonist and explore how the novel’s conflicts affect his development over the course of the novel. An analysis of theme would likely include an exploration of friendship and/or the American Dream, and, in terms of symbolism, an analysis might include examining how the death of Candy’s dog mirrors themes of life on the ranch and foreshadows subsequent events. (See also Table 1.) CLP values reading with literary elements in these ways; however, CLP also emphasizes reading against them to explore how the text sends messages about how the world works. Consider these questions when reading against literary elements (see also Table 1): • Character: Are characters from historically marginalized populations rich and complex or flat and stereotypical? Whose story is emphasized or valorized? Portrayed as a victim or hero? • Plot and Theme: How do the plot and themes support or challenge normative ways of thinking about topics being portrayed (e.g., American Dream)? What role have the themes of this text played in supporting a certain belief system or what might be considered “normal”? • Symbolism: How do symbols reflect particular cultural knowledge? What would someone need to know in order to best understand the various symbols used throughout the text? These questions encourage students to complicate seemingly natural messages the text conveys by calling into question the very aspects of literary analysis we so often take for granted. OMAM provides rich opportunities for reading against the text in terms of characters. Feminist readings of the novel highlight Steinbeck’s negative portrayal of female characters, including Curley’s wife. Additionally, we see opportunities for students to consider the perspective of Crooks, the sole African American character in the novel. Although it can be argued that Steinbeck’s portrayal of Crooks is sympathetic and critiques racial segregation at the time, students might consider the authenticity of Steinbeck’s portrayal. Is Crooks’ character full, round, and dynamic, or is he a token, a stereotype? What would the story be if told from his perspective? These questions could help make students more aware of how canonical novels often marginalize African American characters (cf. Morrison, 1992). And what about Lennie as a character with a cognitive impairment? Or Candy as a character with a physical disability? Students might consider the figurative language Steinbeck uses to describe characters with disabilities. Do loaded words convey negative messages about disabilities? What role do these characters play in the plot of the novel—are they dependent, the subject of others’ pity, always “the problem”? (Myers & Bersani, 2008/2009). Students might also consider Steinbeck’s representation of disabilities and whether those representations are realistic and/or respectful, as well as how Steinbeck’s representation of cognitive and physical impairments constructs attitudes about people with disabilities or about ableism more generally. Regarding theme, students could explore the ideologies inherent in the very idea of the American Dream. What function does having such a national “dream” serve? How does it assign responsibility for success and failure in U.S. culture? In other words, rather than simply having students identify and connect with how their own “American Dream” aligns with George and Lennie’s, analysis encourages them to explore the very idea and consequences of the “American Dream.” In this scenario, students might consider where their ideas about success and the American Dream come from and how the idea of “American Dream” is constructed. In these ways, students are asked to use their exploration of the novel’s themes as a way to better understand how texts reinforce and/or subvert ideologies. Reader Reader Response approaches acknowledge that a text does not have objective, inherent meaning, but that meaning is negotiated in a reader’s transaction with the text. One of the hallmarks of Reader Response approaches involves students making personal connections to the novel. In reading with of OMAM, students are often asked to connect with themes of the American Dream or friendship through prompts like, “Describe a friendship that has been important to you,” or “What’s a ‘dream’ you have for your future?” Finding connections helps students access prior knowledge and gain entry into a text. Though helpful in many ways, these connections often do not stretch students beyond what is familiar or ask them to examine ideologies of texts. In fact, in some cases, depending on students’ identities, stretching too far to make these personal connections may actually undermine efforts to engage students critically with ideas of power and difference. For example, Appleman (2000) illustrates limitations of a Reader Response approach with an example of a student responding to Toni Morrison’s Beloved by saying, “I felt alienated by how their family interacted. I had no basis on which to relate or empathize” (p. 45). Perhaps instead of considering how he did or did not relate to Beloved, this reader could have more productively considered what the novel had to teach him about a perspective other than his own, or perhaps emphasizing how he did not relate to this slave could help him reflect on his own life differently. In other words, relying too heavily on Reader Response can overemphasize the importance “Being ‘critical’ means...also acknowledging how one is privileged.” of “relating” to a book at the expense of examining power and difference. Therefore, in addition to helping students read with a text by making personal connections when fitting, CLP also encourages students to look for opportunities, when appropriate, to read against their own personal connections, to consider how aspects of their own identities—especially their own positions of power and privilege—factor into their experiences with a novel. Some questions in this dimension include (see also Table 1): • How does my identity in terms of race, class, gender, ability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, language, or religion shape my reading of this text? • How do(n’t) I relate with characters in power or with marginalized characters in this novel? How might this positionality shape my reading of the text? Of course, the teaching context—including the student body, school, and community—will factor into teachers’ considerations of these questions and issues. If reading OMAM in a middle-to-upper class teaching context, for example, students might be asked to consider how their social class positions factor into their reading of Steinbeck’s novel. How is their own experience quite different from that of George and Lennie? What does Steinbeck’s commentary on the American Dream have to teach them about their own (and others’) social class position, ideas of meritocracy? What might focusing on the ways they cannot relate to George and Lennie have to teach them about their own power and privilege? Critical literacy often looks for ways to empower students to overcome oppression. When appropriate, teachers could merge a critical literacy approach together with Reader Response to consider, for example, “How are my students reflected in the canonical text we are reading? Do my students experience similar kinds of oppression as that explored in the novel? How does this text help them to understand and/or overcome oppression they face in their daily lives?” At the same time, however, being “critical” means not only learning how one is oppressed but also acknowledging how one is privileged. Overall, questions in this dimension are designed to encourage students to consider perspectives other than their own—and to consider their own perspectives in critical ways. This approach, then, has the potential to make students more aware of power and privilege generally, and the ways they do and do not experience them in their own lives. Assessments Studying canonical literature often results in a summative assessment in which students write literary analysis papers. These types of assessments reflect reading with canonical literature to the extent that they contribute to the normalcy and neutrality of canonical literature curriculum and standards. Students might be asked, for example, to focus their interpretive papers on characterization, symbolism, or thematic analyses. For instance, for OMAM, typical assessments include analytical essays examining the idea of setting or discussing the significance of the book’s title and recurring images and symbols. In some instances, students are asked to argue whether George should be prosecuted for killing Lennie. An against stance toward literature assessment encourages teachers to design assignments that position students as agents of change by setting up opportunities for them to transfer their critical reading of a canonical text to some type of social action. In this way, CLP asks students to engage literary texts for both academic and “real-life” purposes—emphasizing the value their analyses have beyond the classroom. The following questions can be used as first steps in shifting the overarching purpose and assessments for studying canonical literature (see also Table 1): • How can the ideas developed in reading with and against canonical texts be used to inform, persuade, or incite others about oppression and injustice (or whatever particular issues arose within the text studied)? • How might interpretations of canonical texts be used to understand, draw attention to, and interrupt dominant and problematic perspectives in local and contemporary contexts, including the school and community? These and similarly oriented questions provide a broader exigency for studying literature and help answer the age-old question, “Why do we have to do this?” Pushing students to see why and how canonical literature can mean for contemporary, local, and global worlds they live in helps provide students with purpose for the work we ask them to do in literacy classrooms. Thus, these questions encourage students to become critical protégés by producing texts for real audiences and purposes in their own contexts. This dimension of CLP engages students in writing brochures, websites, editorials, public service announcements, research reports, speeches, and other authentic texts to be distributed for sociopolitical critique and transformation. Related to the first dimension discussed (“Canonicity”), for instance, students might, based on their research, propose an alternative reading list for the school’s literacy curriculum to the English Department, administration, or school board. A CLP “assessment” for OMAM might ask students to package what they learned during their reading of the novel and transfer that to their critique of the construction of men, women, ability, class, heteronormativity, or the American Dream in their schools or local communities through their creation and distribution of a range of texts. For example, when Borsheim-Black taught OMAM, she used the novel as an opportunity to teach students to apply different “lenses” (Appleman, 2000) not only to representations of marginalized populations within the novel, but also to the study of a wide range of contemporary texts, such as Disney films, songs, and children’s toys (Petrone & Borsheim, 2008). From their analysis of OMAM, then, students were asked to transfer their analytical tools to media and cultural texts—including those that existed within their schools and communities. How, for example, was race represented within school curricula? How was gender constructed within the school through sports? In terms of social action, the students were asked to write up these analyses for real purposes and audiences. In these ways, OMAM provided a way for students to re-read and re-write their actual worlds—including the very walls of their schools—from a critical perspective. In general, teachers and students could collaborate to design assignments by asking questions like, “How does the novel contribute to my understanding of what is considered normal or expected of me?” Or, “After a critical consideration of the themes in OMAM, what do I want others to know?” Final Considerations We lay out several dimensions of the CLP framework to offer a systematic approach for merging critical literacies and canonical literature. This is not to say that teachers should feel obligated to include every dimension every time or to address them as linear. It is our intention that teachers utilize dimensions that seem most pertinent to particular teaching contexts and texts. While CLP is an approach for the teacher, it is also, ideally, a framework for students to apply the stances of reading both with and against texts. As students become more independent, we could envision offering students Table 1—or adaptations of it—as a handout and letting them guide their own critical reading of texts. As we have found in our own teaching of canonical literature for critical literacy, reading against canonical texts can sometimes leave students feeling unsettled as they begin to question ideas they have always held to be true, fixed, or normal. Indeed, CLP is designed to create this dissonance. As a result, students sometimes demonstrate resistance to the critical process. This resistance, however, can be a sign of learning and engagement with critical perspectives (Petrone & Bullard, 2012). We encourage Take Action STEPS FOR IMMEDIATE IMPLEMENTATION 1. Gauge students’ criticality through a diagnostic assessment or anticipation guide, participate in a preliminary discussion, or read a short text that begins to explore relevant themes or questions connected to a critical framework. 2. Model reading a short text or picture book where you “think aloud” around some of the questions (and your initial responses) posed on the CLP chart. 3. Brainstorm texts that students have studied in previous literacy classes, asking: What stories might these texts collectively tell? What perspectives have been privileged/marginalized? 4. Introduce the CLP chart and assumptions that undergird its questions. Practice exploring questions by breaking students into groups to tackle different dimensions around some common text (e.g., Disney movie, social media website, short documentary). 5. Move forward with group study of a certain text, focusing at first on a couple dimensions but leaving room for student input around all dimensions detailed on the chart. teachers to take advantage of these growing pains as pedagogical opportunities by asking themselves and their students: Why might I be feeling resistance, anger, sadness, or disillusionment during or after critically reading this text? Finally, our consideration of canonical literature is not an endorsement for the maintenance of traditional literature curriculum. We continue to advocate that curriculum be revised to include texts by a more diverse representation of authors. However, we also endorse reading against canonical novels to make visible dominant ideologies, narratives, and assumptions that are embedded in the literature curriculum. We recognize the power canonical novels hold to reaffirm cultural capital. Because of this power—and precisely because these texts are such pillars of secondary classrooms—they need to be subjected to a critical eye. By reading against canonical literature, students might begin to see “canonical” messages around them and become more aware of the influence these messages could—as opposed to would or should—have on them. References Applebee, A.N. (1993). Literature in the secondary school: Studies of curriculum and instruction in the United States. Urbana, IL : NCTE. Applebee, A.N. (1996). Curriculum as conversation: Transforming traditions of teaching and learning. Chicago, IL : University of Chicago Press. Appleman , D. (2009 ). Critical encounters with high school English: Teaching literary theory to adolescents (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Beach, R. (2006). Teachingmedialiteracy.com: A web-linked guide to resources and activities. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Blackburn, M., & Smith, J.M. (2010). Moving beyond the inclusion of LGBTQ-themed literature in English language arts classrooms: Interrogating heteronormativity and exploring intersectionality. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(8), 625– 634. Borsheim-Black, C. (2012). Not as multicultural as I’ d like: White English teachers’ uses of literature for multicultural education in predominantly White contexts. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Comber, B., & Simpson, A. (2001). (Eds.) Negotiating critical literacies in classrooms. Mahwah, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press. Habermas , J. (1975). Legitimation crisis. London, England : Beacon Press. Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreira, A., Granville, S., & Newfield, D. (2013). Doing critical literacy: Texts and activities for students and teachers. London, England: Routledge. Luke, A. (2000). Critical literacy in Australia: A matter of context and standpoint. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43(5), 448 – 461. Macaluso, M. (2013, April). Canonical conundrum: Exploring canonization with secondary English teachers. Paper presented at AERA Convention, San Francisco, CA. Marshall, E., & Özlem, S. (2011). Rethinking popular culture and media. Milwaukee, WI : Rethinking Schools. McLaughlin, M., & DeVoogd, G.L. (2004). Critical literacy: Enhancing students’ comprehension of text. New York, NY: Scholastic. Morrell, E. (2009). Critical research and the future of literacy education. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (2), 96 –104. Morrell, E. (2004). Becoming critical researchers: Literacy and empowerment for urban youth. New York, NY: Peter Lang. Morrison , T. (1992). Playing in the dark: Whiteness and the literary imagination. Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press. Myers, C., & Bersani, H. (2008/2009). Ten quick ways to analyze children’s books for ableism. Rethinking Schools, 23 (2), 1–5. Petrone, R., & Borsheim, C. (2008). “It just seems to be more intelligent”: Critical literacy in high school English. In (Ed.) L. Wallowitz. Critical literacy as resistance: Teaching for social justice across the secondary curriculum. New York, NY: Peter Lang. Petrone, R., & Bullard, L. (2012). Reluctantly recognizing resistance: An analysis of representations of critical literacy. English Journal, 102 (2), 122–128. Simmons, A.M. (2012). Class on fire: Using The Hunger Games trilogy to encourage social action. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56 (1), 22–34. Stallworth, J.B., & Gibbons, L. (2012). What ’s on the list … now? A survey of book-length works taught in secondary schools. English Leadership Quarterly, 34 (3), 2–3. Stotsky, S. (2010 ). Literary study in grades 9, 10, 11: A national sur vey. Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers. Vasquez, V.M., Stacie, L., Tate, S.L., & Harste, J.C. (Eds.) (2013). Negotiating critical literacies with teachers: Theoretical foundations and pedagogical resources for pre-service and in-service contexts. London, England: Routledge. Zinn, H. (1999). A people’s history of the United States: 1492present. New York, NY: HarperCollins. More to Explore CONNECTED CONTENT-BASED RESOURCES ✓ Berhman, E. H. ( 2006 ). Teaching about language, power, and text: A review of classroom practices that support critical literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49 ( 6 ), 490 – 498. ✓ Morrell, E. ( 2007). Critical literacy and urban youth: Pedagogies of access, dissent, and liberation. London, England : Routledge. ✓ Murray, M., & Collins, G. ( 2011, November 18). Exploring diversity through children’s literature: Supporting students in becoming critically literate. Retrieved April 12, 2014 from http://quest-criticalliteracy.wikispaces.com/ ✓ Pandya, J., & Avila, J. (Eds.) ( 2013 ). Moving critical literacies forward. London, England : Routledge. ✓ Stevens, L.P., & Bean, T.W. ( 2007). Critical literacy: Context, research, and practice in the K-12 classroom. Thousand Oakes, CA : Sage.