Document 13550472

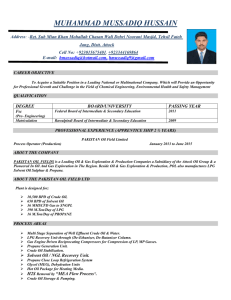

advertisement