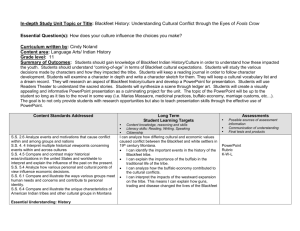

As long as the grass grows and the waters flow :... by Thedis Berthelson Crowe

advertisement