From the sixth floor to the Copper Dome : The... by Bradley Dean Snow

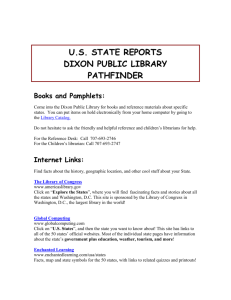

advertisement