International Public Policy Review

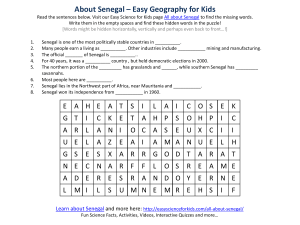

advertisement