NEW LABOUR, NEW AID? A QUANTITATIVE EXAMINATION OF THE DEPARTMENT FOR

advertisement

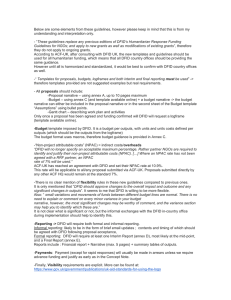

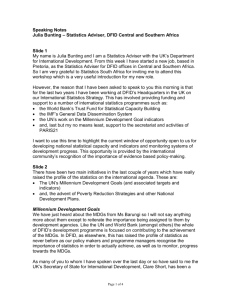

NEW LABOUR, NEW AID? A QUANTITATIVE EXAMINATION OF THE DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Alan Webster ABSTRACT International aid policy under New Labour has been widely praised as one of the world’s most progressive but it has not yet been subject to critical, quantitative review. This paper addresses that gap, comparing aid policy in the eight years before and after 1997. It concludes that New Labour has pursued a policy that has seen significantly larger sums directed at the countries in most need, and in the form most effective for development. The paper also argues that British aid has been transformed into a more purely altruistic policy, with the removal of economic conditions that had typified it in the past. Finally, this research argues that there has been a revolution in the character of British aid as New Labour has gradually moved towards initiating genuine partnerships with developing countries in contrast to the subjugation of old. In short, the paper concludes that British aid has undergone a dramatic and positive change in the last decade making it largely deserving of the admiration it has received. Keywords: International Development, Aid Policy, New Labour, DFID INTRODUCTION The New Labour government that came to power in 1997 did so pledging a comprehensive and sweeping reform of policies after eighteen years of “failed” Conservative rule.1 British overseas aid was not to be excluded as its manifesto claimed a Labour government would “attach much higher priority to combating global poverty and underdevelopment” and to reinstate the party’s tradition, since 1964, of creating a separate ministry responsible for overseeing this matter. In the ten years since this new Department for International Development (DFID) was established, British aid policy has been lauded as “a model for other rich countries.”2 Despite more than a half century of Western overseas aid programmes, the United Labour Party, New Labour: Because Britain Deserves Better (Labour Party: London, 1997): 3. O. Barder, “Reforming Development Assistance: Lessons from the UK Experience,” Centre for Global Development Working Papers 70 (2005): 3. 1 2 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 Nations estimates that today more than one billion people still remain in abject poverty.3 If developed countries are truly committed to assisting the development of the world’s poorest nations, then it is vital that the apparently successful policies embraced by DFID are scrutinised. Thus, this paper aims to identify the changes in aid policy pursued under New Labour that initiated the positive comments referenced above. It shall proceed by first examining the fundamental question about aid’s effectiveness in achieving development through a discussion of the neo-liberal critique of aid before broadening the issue to consider a more contemporary conceptualisation of the issue. This shall then lead to an exploration about the changing historical priorities of aid, considering whether past aid policies were actually targeted at achieving development. Then, the early, largely positive, reviews of DFID’s work shall be examined, which then shall lead to questioning whether this praise is deserved, by using a quantitative examination of whether British policy has actually altered to a more progressive state under New Labour. Finally, the paper will conclude that New Labour has largely pursued an aid policy that is both significantly different to that which came before it and systematically targeted at improving the lives of the world’s most vulnerable individuals. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPTUALISATION OF INTERNATIONAL AID New Labour came to power during a period of reflection and change in the field of international development. The end of the Cold War, the miraculous economic growth in East Asia and the failings of previous aid policies raised a myriad of questions about the future of development policy across the globe. An understanding of the evolution of aid policy from its post-war birth to the contemporary consensus, examining the changes in the perceived ‘best practise’ of aid is vital to framing the positive reactions to the first ten years of the Department for International Development. TRUMAN TO BURNSIDE AND DOLLAR: SIXTY YEARS OF AID There are two broad areas into which one can divide the debate around aid: the impact of aid on recipient countries, and the factors that influence donors’ decisions about aid spending. The first of these has been particularly controversial since aid-giving commenced. AID’S IMPACT In promising sums of money to developing nations in order to “relieve the suffering of …people…and help them realise their aspirations for a better life”, it was the 1949 inauguration speech of President Truman4 that initiated the spending of more than $1.6 United Nations, Human Development Report 2006 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). M. Gronemeyer, “Helping,” in The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, ed. W. Sachs (London: Zed Books, 1992): 61. 3 4 5 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW trillion in aid over the last six decades5. However, the existence of more than one billion people in abject poverty today raises difficult questions about the use of aid as a tool for assisting development and reducing poverty. Western aid-giving emerged rashly in response to the speech of President Truman, preceding the establishment of development economics as an academic pursuit. This “unprecedented economic experiment”6 led to haphazard spending before it could be subject to thorough study. By the 1950s and 1960s, however, development economics was simultaneously measuring aid’s effects and actively shaping aid policies.7 These early academic theories argued that ‘under-development’ was due to ‘gaps’ in countries’ economies: a savings gap that would be overcome by greater investment, and a capacity gap that would be overcome by the importing of Western capital and technical knowledge.8 Consequently, development economists employing Harrod9-Domar10 or Solow11 models of economic growth believed that aid could provide the necessary catalyst for growth through the stages of Rostow’s ‘take-off’ model.12 Such a belief lead to donor governments focusing resources on discrete, capital-intensive projects, often dams and roads, in the belief that such an investment would fuel growth.13 But such policies proved to be largely wasteful. The projects produced only “islands of excellence”14 which contributed little towards recipient nations’ development:15 a fact recognised as early as 1969 when the World Bank’s own Pearson Commission reported that such projects had “little impact on....global development objectives.”16 Development economics progressed, but economic growth still failed to materialise from the subsequent ‘Washington Consensus’ policies of the 1980s. The unwavering neoliberal macroeconomic reforms promoted by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund proved to be ill-suited for developing countries.17 The requirements for fiscal conservatism caused a decrease in education and health funding while rapid and C. Lancaster, Foreign Aid; Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006): 2. P.D. Boone, “Politics and the Effectiveness of Aid,” European Economic Review 40, no.2 (1996): 260. 7 H. Hansen and F.Tarp, “Aid Effectiveness Disputed,” Journal of International Development 12 (2000): 375-398. 8 ActionAid, Real Aid 2: Making Technical Assistance Work (London: ActionAid, 2006): 26. 9 R.F. Harrod, “An Essay in Dynamic Theory,” Economic Journal 49 (1939): 14-33. 10 E.D. Domar, “Capital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment,” Econometrica 14 (1946): 137-147. 11 R. Solow, “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” Review of Economics and Statistics 39 (1957): 312-320. 12 W.W. Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960). 13 T. Killick, “Policy Autonomy and the History of British Aid to Africa,” Development Policy Review 23, no.6 (2005): 668. 14 R. Young, “New Labour and international development: a research report,” Progress in Development Studies 1, no.3 (2001): 250. 15 A. Hewitt, “British Aid: Policy and Practice,” ODI Review 2 (1978): 54. 16 ActionAid: 31. 17 J. Stiglitz, “The Post Washington Consensus Consensus,” (speech to the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Sao Paolo, Brazil, August 22, 2005), http://www2.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/download/speeches/IFIs/Post_Washington_Consensus_Consensus.p pt. 5 6 6 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 unmitigated financial and trade liberalisation caused domestic industries to suffer.18 The resultant “lost decade” of growth occurred despite large sums of aid being spent, leading to further questioning of its effectiveness, and a subsequent ‘aid fatigue’ setting in amongst Western governments.19 Such experiences were cited by aid-cynics such as Peter Bauer, who has called for Official Development Assistance (ODA) to be “terminated.”20 Aid serves only, he argues, to create corrupt and uncompetitive recipient countries wholly dependent on rich states.21 Despite lacking empirical analysis or data, Bauer’s argument reflects a view that has been asserted by many critics for many decades.22 The criticisms frequently levelled at aid’s effectiveness were largely only political or ideological. However, when, employing a quantitative analysis, Peter Boone23 came to similar conclusions as Bauer, there was a resurgent interest in the question of aid’s effectiveness,24 just as New Labour was coming to power. Studying decades of data for almost 100 developing countries, Boone’s seminal work concluded that aid did not significantly increase a state’s investment or growth rates; nor did it benefit the poorest sections of society. Instead, he argued that, in most cases, aid only increased the size of recipient governments’ consumption rates by around three-quarters of the volume of aid.25 Boone’s empirics supported what had previously only been political scepticism of aid’s effectiveness and, while it was published at the very end of the Conservative government, it appeared to justify the decrease in the aid budget in all eighteen years of its rule.26 Arguably, however, Boone’s results are neither surprising, nor actually disheartening for modern advocates of foreign aid. While Boone’s analysis covered more than thirty years of data, crucially, it ended in 1993.27 As such, the lack of a relationship he found between aid and economic growth is only reflective of a lack of a relationship between old aid and economic growth – aid that was not always attempting to assist development, as shall be discussed in due course. Four years later, and using the same dataset as Boone, World Bank officials Craig Burnside and David Dollar28 came to a conclusion that would have very different implications for the policies of a new government that read it. 18 W. Easterly, “The lost decades: Developing countries’ stagnation in despite of policy reform 1980—1998,” Journal of Economic Growth 6, no.2 (2001): 137-157. 19 J. Simensen, “Writing the History of Development Aid,” Scandinavian Journal of History 32, no.2 (2007): 175. 20 P. Bauer, “Foreign Aid: Mend It or End It?” in Aid and Development in the South Pacific, eds. P. Bauer, S. Siwatibau, and W. Kasper (Australia: Centre for Independent Studies, 1991): 17. 21 Ibid. 22 See for example M. Friedman, Capital and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962); S. Djankov, J. Garcia-Montalvo and M. Reynal-Querol, “Does Fair Aid Help,” Cato Journal 26, no.1 (2006): 1-28. 23 P. Boone, “Politics and the Effectiveness of Aid,” European Economic Review 40, no.2 (1996): 289-329. 24 W. Easterly, R. Levine, and D. Roodman, “New Data, New Doubts: A Comment on Burnside and Dollar’s ‘Aid, Policies and Growth’ (2000),” Centre for Global Development Working Papers 26, http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/2764, 26. 25 P. Boone, 314. 26 P. Williams, British Foreign Policy Under New Labour 1997 – 2005 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 17. 27 P. Boone, 289. 28 C. Burnside and D. Dollar, “Aid, Policies, and Growth,” The American Economic Review 90, no.4 (2000): 847-868. 7 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Burnside and Dollar’s analysis showed that while development generally failed to result from aid, this was not the case in some recipient nations. In those developing countries with good fiscal, monetary and trade policies as well as sound government institutions, aid had a significant, positive impact on development.29 But they found no evidence that aid actually caused recipient countries to adopt the same policies that would have a positive effect on its ability to help development.30 Thus they argued for aid to be made conditional on such reforms. Burnside and Dollar’s “extraordinarily influential”31 (Easterly et al., 2003: 1) paper has subsequently had considerable impact on aid policy worldwide, and gave extra support to the concept of ‘good governance’ in the development field. ‘Good governance’ has been a guiding principle for aid-giving for more than a decade32 and has reflected a change in economic and political thinking since the failure of the structural adjustment policies of the Washington Consensus. While subject to various definitions, one can consider good governance as countries’ dedication to transparent, consultative and democratic forms of government aimed at bettering citizens’ lives.33 Inspired by the growing body of evidence34 that came to a head with Burnside and Dollar, economists and politicians increasingly saw ‘conditionality’ as a way to ensure that aid monies would be ‘better spent’ by recipient nations35 and achieve the development which had failed to materialise in the past. However, the use of such methods is far from uncontroversial. Non-governmental organisations36 and recipient nations themselves37 have been critical of conditionality’s intentions, equating it to a reemergence of Western imperialism. While academics, including Svensson,38 have argued that it actually fails to produce reform because donor inertia means that funds are dispersed even when recipients miss targets and fail conditions. As an attempted softening of such criticism, there has been a growing move by donor countries to embrace ‘partnerships’ in development policy, working more closely alongside recipients to combat poverty together.39 This commitment towards endogenous, domestically-owned development policies has manifested itself in Ibid., 847. Ibid., 847. 31 Easterly et al., 1. 32 M. Doornbos, “Good Governance: The Rise and Decline of a Policy Metaphor?,” Journal of Development Studies 37, no.6 (2001): 93. 33 United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “What Is Good Governance?” About Us, http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/ProjectActivities/Ongoing/gg/governance.asp (accessed 18 January 2009). 34 See for reference Easterly and Rebelo, 1993; Easterly and Levine, 1997. 35 Easterly et al., 1. 36 ActionAid. 37 L. Green and D. Curtis, “Bangladesh: partnership of posture in aid for development?,” Public Administration and Development 25, no.5 (2005): 389-398. 38 J. Svensson, “Why conditional aid does not work and what to do about it,” Journal of Development Economics 70, no.2 (2003): 381-402. 39 T. Hattori, “Giving as a Mechanism of Consent: International Aid Organisations and the Ethical Hegemony of Capitalism,” International Relations 17, no.2 (2003): p.160. 29 30 8 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 academic support for direct government budget support by donors, as opposed to the donor-controlled project-based and ‘technical assistance’ aid schemes of old.40 But, the concept of ‘partnerships’ in development has been severely criticised as empty rhetoric, and disguising a continued subjugation of recipients41 that has tainted aid-giving for decades. GIVING AID The rise of good governance and partnerships came at a time of change in the second of the two broad areas of development research: the motivations for donors’ aid-giving. Historically these had been far from purely benevolent selflessness as combinations of commercial, historical and geopolitical ties shaped aid decisions.42 Indeed, Burnside and Dollar’s own empirical study found that bilateral aid had been most influenced by donor interests, rather than recipient countries’ genuine need. 43 For the United Kingdom, aid has traditionally been a remnant of its imperial history, with the overwhelming majority being spent on former colonies44 because of the “special responsibility” that its Overseas Development Ministry45 claimed the country had inherited. The economic and social requirements of less developed countries was clearly secondary to donor’s own political policy. Generations of governments were also committed to using aid as a tool of British economic policy, giving rise to the commercial “tying” of aid, with monies being ‘donated’ on the condition that it was spent on British goods and services which were often more expensive than the competitive world market price.46 The use of tied aid has been criticised heavily by academics, including Oliver Morrissey who claims that it significantly decreases the efficiency of aid47 and is “unlikely to be of a net economic benefit to . . . [developing countries].”48 The use of one form of aid in particular has been subject to vocal criticism. ‘Technical assistance’, defined by the OECD49 as aid concerned with the use of donor’s expert knowledge and research, has been argued to have a disappointing record for assisting Simmensen, 175. G. Crawford, “Partnership or Power? Deconstructing the ‘Partnership for Government Reform’ in Indonesia,” Third World Quarterly 24, no.1 (2003): 139-159; Green and Curtis; D. Slater and M. Bell, “Aid and the Geopolitics of the PostColonial: Critical Reflections on New Labour’s Overseas Development Strategy,” Development and Change 33, no.2 (2002): 335-360. 42 A. Alesina and D. Dollar, “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economics 5, no.1 (2000): 33-63. 43 C. Burnside and D.Dollar (2000), 848. 44 J. Tomlinson, “The Commonwealth, the Balance of Payments and the Political of International Poverty: British Aid Policy 1958 – 1971”, Contemporary European History 12, no.4 (2003): 413. 45 Overseas Development Ministry, “What is British Aid?: 67 Questions and Answers,” (London: HMSO, 1967), 3. 46 A. Hewitt, “British Aid: Policy and Practice,” ODI Review 2 (1978): 60. 47 O. Morrissey, “ATP is Dead: Long Live Mixed Credits,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 248. 48 O. Morrissey, “An Evaluation of the Economic Effects of the Aid and Trade Provision,” Journal of Development Studies 28, no.1 (1991): 104. 49 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Trade-Related Assistance: What Do Recent Evaluations Tell Us? (OECD: OECD Publishing, 2007). 40 41 9 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW development50. One study concluded technical assistance to have had a negative impact on economic growth,51 while others have claimed it to be rarely demand-driven, but instead driven by donor governments.52 Developmental needs were still explicitly secondary in British aid policy in 1980 when the Minster for Overseas Development, Neil Marten, stated that the government would “give greater weight in the allocation of our aid to political, industrial and commercial objectives alongside our basic development objectives.”53 As such, the Thatcher and Major era of British government saw British aid still dominated by stand-alone projects and a significant proportion remained tied. It was during this administration that the perceived wisdom of development economics evolved once more, as the structural adjustment policies of the Washington Consensus gave way to a focus on poverty reduction as being the most important aim of aid, typified by the 1997 Human Development Report which considered this to be a “moral imperative and a practical quest.”54 THE DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT The government that emerged from the 1997 election was one committed to sweeping reform of British policies. The landslide victory of New Labour was won on the back of a campaign that had almost exclusively focused on domestic policies.55 Nevertheless, its manifesto did contain fleeting references to foreign policy and, most pertinent to this study, is the one short paragraph concerning international development. The manifesto mirrored the latest Human Development Report published only weeks earlier, acknowledging the “clear moral responsibility”56 developed countries had to eradicate global poverty. A Labour government would do this, in part, by establishing a new, independent Department for International Development headed by a Cabinet Minister to “attach much higher priority to combating global poverty and underdevelopment”57 and implicitly suggesting that there would be a significant change in the policies pursued. The new department was to have a policy remit that went beyond simply distributing aid but encompassed a broad range of issues including the global environment, world trade, debt sustainability, and encouraging democratic institutions.58 ActionAid. G. Mavrotas and B. Ouattara, “Aid disaggregation and the public sector in aid-recipient economics: Some evidence from Cote D’Ivoire,” Review of Development Economics 10, no.3 (2006): 441. 52 M. Godfrey et al., “Technical Assistance and Capacity Development in an Aid-dependent Economy: The Experience of Cambodia,” World Development 30, no.3 (2002): 355-373. 53 House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, 20 February 1980 columns 464-465. 54 United Nations, Human Development Report 2006, 106. 55 P. Williams, 16. 56 Labour Party. 57 Ibid. 58 J. Vereker, “Blazing the Trail: Eight Years of Change in Handling International Development,” Development Policy Review 20, no.2 (2002): 135. 50 51 10 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 Within months of the new department’s creation, it had published a “bold”59 White Paper promising significant reform of Britain’s development policy: greater spending on aid policy, an end to tying, and a revised focus on poverty reduction in those countries with the greatest development needs60 – policies identical to those of the current ‘best thinking’ identified earlier in this section. The White Paper also dedicated no fewer than twenty pages to another favoured issue of the development field, by pledging to establish partnerships with those developing countries that were committed to democracy and the eradication of poverty.61 The establishment of DFID and its “bold” White Paper led to an initial flurry of positive writing on the department, receiving praise from academics,62 NGO officials,63 and even muted approval from opposition politicians.64 Yet, there were still those who were not convinced by the new department’s actions. Bill Gould65 remained one such sceptical early voice. While largely positive of the leadership exhibited by the new Secretary of State for International Development, Clare Short, he was unconvinced by the actual change in policies promised in the White Paper, which contained, he argued, “little that is…operationally radical” from the previous eighteen years. 66 However, four years later and with the benefit of seeing DFID working in practise, Slater and Bell came to a different conclusion, suggesting that New Labour’s policies did constitute a significant change from those of the past.67 The new government’s emphasis on the moral basis of aid, as part of its much derided ‘ethical’ foreign policy68 was, they claim,69 a novel approach to development. Yet, at the same time, they suggest that its policies of a focus on poverty reduction was merely an extension of those pursued under Lynda Chalker – the last Conservative minister for international development.70 The lack of quantitative study, however, makes the divergent conclusions of Gould, and Slater and Bell largely unfulfilling. A more recent contribution from Paul Williams71 provides an insightful and detailed background on the aid policies pursued under successive British governments. He, like R. Young, “New Labour and International Development: a research report,” Progress in Development Studies 1, no.3 (2001): 247. 60 Department for International Development, Eliminating World Poverty: A Challenge for the 21st Century, (London: The Stationery Office): 5. 61 Ibid, 22-41. 62 A. Hewitt and T. Killick, “The 1975 and 1997 White Papers Compared: Enriched Vision, Depleted Policies,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 51-67. 63 A. Whaites, “The New UK White Paper on International Development: An NGO Perspective,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 203-213. 64 A. Goodlad (1998), “The View from the Opposition Benches,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 195201. 65 B. Gould, “New Labour, new international development policy?” Third World Policy Review 20, no.1 (1998): iii-vi. 66 B. Gould, 4. 67 D. Slater and M. Bell, 340. 68 C. Allen, “Britain’s Africa Policy: Ethical or Ignorant?” Review of African Political Economy 77 (1998): 33-63. 69 D. Slater and M. Bell, 341. 70 Ibid. 71 P. Williams. 59 11 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Slater and Bell, found the moralism attached to development policy by New Labour as the key departure from the past72, arguing that its broad aims and rhetoric are not dissimilar from previous governments’. But, he, like all other authors, is silent about the specific policies and spending decisions pursued and the extent to which they are actually a significant break from the past. Attempting to overcome this shortcoming shall drive the remainder of this paper. HYPOTHESES The preceding examination of the evolution of aid identified several substantive gaps in the existing body of research on British aid policies. Specifically, while there has been a small number of publications reviewing policy over the last ten years, none of these have subjected their assertions or conclusions to statistical testing. Therefore, this paper aims to analyse the specific spending decisions made in the last ten years to more fully answer the question of “how has British aid policy changed under DFID?”. More specifically, four identifiable hypotheses can be identified that would confirm DFID as deserving of its accolades, according to the current “best thinking” on international aid. • • • • H1: the total aid budget under DFID has significantly increased. H2: economic need has become a more significant factor in determining British aid flows since 1997. H3: there has been a shift in British aid spending towards direct budgetary support away from funding projects H4: there has been a move from commercially-tied aid to conditionality based upon political reforms. DATA AND METHODOLOGY For each of the first four distinct hypotheses, the analysis will employ a quasilongitudinal approach, comparing eight annual intervals of British aid policy before and after 1997.73 In order to identify whether the change in government at this critical juncture brought with it a significant change in policy, analysis of variance (ANOVA) models shall be used to compare data before and after the critical juncture of 1997. The key sources of data for the quantitative analysis that is central to this paper were DFID’s own annual publications ‘Statistics on International Development’, a series of requests to the department under the 2000 Freedom of Information Act for figures not previously released before its implementation, and the Organisation for Economic Co72 Ibid., 219. 73 The 2005 figures were the most recently available at the time of writing. 12 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 operation and Development (OECD)’s Development Co-operation Directorate’s data on aid flows. The first variable, total aid budget, was measured simply as the total bilateral aid spending in any one year. Concentrating on bilateral aid ensured that only those funds over which Britain has complete control were investigated, removing those monies that reach recipient countries via multinational organisations. The second hypothesis stated that a greater share of bilateral aid would be spent on countries with greater ‘need’. In order to measure recipients’ development status, the United Nation’s preferred measure, the Human Development Index, was employed as it provides a broader conceptualisation of development than a solely economic measurement such as the average Gross National Income, by incorporating life expectancy and illiteracy rates74. In total, aid receipts for 172 countries were analysed which consisted of all countries defined by the United Nations as low- or middle-income countries at some point between 1990 and 2005 as well as the nineteen other countries that received British aid during this time period. Holding for recipient countries’ population,75 a regression analysis was preformed for each of the annual intervals under study, establishing the extent to which aid receipts from Britain have been dependent on need, and then an ANOVA analysis was used to determine whether this did indeed become a more significant factor under New Labour. In order to investigate the changing composition of Britain’s aid budget under the different governments, the British government’s own categories of aid were used which include ‘direct budget support’, ‘project aid’, ‘technical assistance’, ‘humanitarian aid’, and ‘debt relief’ (categories which fortunately survived the change in government). The relevant proportion of each category in each of the annual budgets shall be analysed, and then an ANOVA analysis performed to identify any significant change in spending priorities since 1997. The fourth hypothesised shift in policy, from economic- to political-conditionality, is more difficult to quantify due to the intricacies of the specific conditions and requirements attached to British aid. Thus, primary sources were relied upon, particularly a report produced by DFID and development consultancy firm Mokoro76 reviewing the changing terms of British aid, and DFID’s own official paper on ‘Rethinking Conditionality’.77 In addition, a small number of interviews were conducted with officials from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with detailed first-hand United Nations, Human Development Report 2006. Population figures for each of the 16 years were gathered from the relevant United Nations Human Development Report. 76 Department for International Development and Mokoro, DFID Conditionality in development assistance to partner governments (London: The Stationery Office, 2005). 77 Department for International Development and Mokoro, Partnerships for Poverty Reduction: Rethinking Conditionality (London: The Stationery Office, 2005). 74 75 13 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW knowledge about the realities of British aid, which did not necessarily reflect the official government policy.78 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION This section aims to identify the changes in spending and policy decisions that the New Labour government has pursued using the first four hypotheses above. H1: TOTAL SPENDING ON AID The Labour government that swept to power in 1997 did so on a manifesto that had only one fleeting reference to international development. Yet that one paragraph contained a pledge for “a much higher priority”79 to international development: a pledge that has been borne out consistently in the government’s total spending on aid. Britain’s total bilateral aid budget has increased dramatically in the last two decades from a little over £800 million in 1990 to close to £4.5 billion in 200580 as figure 1 above clearly illustrates. Even allowing for the fact that the first two years of DFID’s existence saw no real increases due to Labour’s manifesto pledge to match the previous Conservative government’s spending plans, one can see a significant and sustained increase in total bilateral aid spending under New Labour. 5000 Total bilateral spending (£ million) . (Unadjusted for inflation) 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Figure 1: Total bilateral aid spending 1990 – 2005. Colour coded by government – red (Labour) and blue (Conservatives). Data from DFID, Statistics on International Development 2006. For reasons of brevity, source data, and the ANOVA tests of significance are not shown in this paper. Any interested readers can contact the author, through the journal, for more details. 79 Labour Party. 80 Department for International Development, Statistics on International Development 2006 (London: The Stationery Office, 2006). 78 14 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 However, Figure 1 above also demonstrated that the most dramatic increases in aid spending occurred after 2003. More careful study of DFID’s data reveals that a large proportion of this aid went on post-conflict reconstruction in Afghanistan and Iraq where £1.5 billion of the UK’s Official Development Assistance was spent in 2005.81 Nevertheless, even if one was to exclude these countries, it is clear that the British aid budget under DFID has been expanded considerably, thus confirming hypothesis 1 from the previous section. Yet merely throwing money at the problem of decades of underdevelopment is not sufficient, as the $1.6 trillion82 spent since 1950 makes apparent. A truly effective aid policy, therefore, needs greater attention given to both the recipients and the form of aid. H2: RECIPIENTS OF AID The issue of aid’s recipients was one that Labour’s manifesto mentioned briefly, with a pledge to shift aid resources to helping “the poorest people in the poorest countries.”83 The post-conflict spending in Iraq and Afghanistan – two countries considered middleincome countries by the United Nations84 – questions whether this has been a pledge that DFID has been able to fulfil. An analysis of the spending decisions made, however, shows that there has been a gradual move towards greater spending on the developing countries with the greatest need. Figure 2 below shows that there has been a general trend for more of DFID’s money to be spent on those countries with the lowest HDI scores – those, therefore, that have the greatest “need”. ANOVA analysis confirms that DFID spending has been significantly more focused upon the very poorest developing countries. Department for International Development, Statistics on International Development 2006. Lancaster, 2. 83 Labour Party. 84 United Nations, Human Development Report 2006. 81 82 15 0 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 -0.05 1990 Regression co-efficients for relationship between aid receipts and HDI INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW -0.1 -0.15 -0.2 -0.25 -0.3 -0.35 -0.4 Figure 2: Trend in relationship between aid receipts and HDI status, 1990 – 2005. Colour coded by government – red (Labour) and blue (Conservatives). Data from DFID, Statistics on International Development 2006. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for example – one of the least developed countries in the world – has benefited from a significantly larger investment under DFID, totalling almost £400 million in the last three years under study:85 a dramatic increase from the £9 million it received in the first three years of the 1990s. Under the Conservative government of this period, aid was still concentrated heavily on former British colonies, making up over 71% of the total bilateral budget, in contrast to the 44% in 2005.86 Thus it appears that DFID has genuinely moved away from the perception of aid simply being a tool of a broader foreign policy, to becoming a distinct area of government in itself, with its own goals for which to aim. However, there is still considerable room for a greater commitment on DFID’s behalf to ensure aid is better focused. India, a country that has seen a remarkable economic transformation in the last two decades, still receives extraordinarily large sums of money – in 2005, it was second only to Iraq, receiving a total of £579 million. While India does have an extremely large population, it still receives more than five times more per head than Mali, which is consistently amongst the poorest three nations in the world.87 Guinea-Bissau, a country amongst the world’s least developed, has not received any aid from DFID since 2001, despite its average annual income of $736, and an average life expectancy of 44 years.88 DFID’s continued ability to concentrate much of its resources on the least developed Department for International Development, Statistics on International Development 2006. Author’s calculations from DFID, Statistics on International Development 2006. 87 Author’s calculations from DFID, Statistics on International Development 2006. 88 United Nations, Human Development Report 2006. 85 86 16 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 nations, despite enormous sums being spent in Iraq and Afghanistan presents somewhat of a puzzle. However, closer analysis of DFID’s spending priorities reveal that other ‘middle-income’ countries have seen their aid receipts cut dramatically in order to maintain the department’s development-focus. Pakistan, Peru and South Africa, for example, saw significant decreases in DFID spending in the aftermath of the conflicts from combined receipts of £237 million in the year before Operation Iraqi Freedom to just £136 million in 2005.89 These cuts have occurred despite an explicit recognition by DFID that middle-income countries are vulnerable to falling back to low-income status, as 38 countries have done in the last two decades.90 Nevertheless, these failures should not totally detract from what has been a systematic reform of policy undertaken in the last decade, which now sees British aid more targeted at the very poorest countries in the world – a significant improvement on the decades of policy identified by Alesina and Dollar91 as being primarily driven by historical and geopolitical links. H3: TYPE OF AID The form of Official Development Assistance (ODA) is undoubtedly integral to its ability to promote development, as the ill-fated experiences of early aid’s fixation with capitalintensive projects testifies. DFID’s early publications and reports made no explicit reference to the type of aid that would be pursued, but analysis of its spending decisions finds that there has been a sustained shifting of priorities. The most apparent recent trend in Figure 3 overleaf is the significantly smaller proportion of funds spent on technical assistance by New Labour, from a peak of 62% in the year it came to power, to less than 28% in 2005. This has been a move that will have been welcomed by the non-governmental organisations and development academics who heavily criticised technical assistance, as was noted previously. Interviews with development agency officials (conducted July – August 2007) confirm that DFID’s diminishing spending on this sector is considered an indication of its increasingly progressive nature. Yet the continued existence of a considerable proportion of ODA being spent on technical assistance proves frustrating to many advocates of ‘better’ aid. One NGO official was extremely sceptical about technical assistance even being considered aid, due to its dubious credentials in supporting development and poverty reduction, calling it “phantom aid … whose inclusion in ODA is somewhat…misleading”.92 Author’s calculation from Department for International Development, Statistics on International Development 2006. Department for International Development, Achieving the Millennium Development Goals: The Middle Income Countries – a strategy for DFID 2005 – 2008 (London: The Stationery Office: 2004): 5-6. 91 Alesina and Dollar. 92 Anonymous (NGO official), interview by Alan Webster, August 2007. 89 90 17 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW 70 Percentage of bilateral ODA 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 Technical Assistance 1995 1996 1997 Budget Support 1998 1999 2000 Emergenc y Aid 2001 2002 Projects 2003 2004 2005 Debt Relief Figure 3: Trend in type of bilateral aid, 1990 – 2005. Data from DFID, Statistics on International Development 2006. The continued decrease in the proportion of British aid spent on technical assistance was underlined in 2005 when it was exceeded by the funds spent on direct budget support. Under DFID, budget support almost trebled its share of British aid spending, reaching a high of over 28% in 2005.93 The then Secretary of State for International Development, Clare Short, made her department’s view clear when asserting that “budgetary aid… in the end, is the most effective” for assisting development.94 The new government’s pledge to establishing partnerships with developing countries appears to have been fulfilled, partly confirming hypothesis 2, with more aid provided in a form that leaves its use up to recipient governments, showing DFID’s “real commitment to…[recipient] country ownership…which is really good” as one NGO official put it.95 The proportion of aid spent on projects has seen a slight, but significant increase under DFID, contrary to hypothesis 3. However, the nature of aid projects sponsored by DFID has changed dramatically from the disjointed infrastructure projects identified as being ineffectual for development in the literature review. DFID has increasingly utilised endogenous, demand-driven programmes run by nongovernmental organisations as a means to furthering its broad goal of poverty reduction. Its Partnership Programme Agreement scheme invites proposals from British, as well as recipient countries’, civic society organisations for programmes which they consider to be beneficial for development, which are then assessed against DFID’s own development aims.96 Interviews (conducted July-August 2007) with officials from British-based NGOs See Appendix 2, tables 2 and 8. House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, May 14 2002 column 130. 95 Anonymous, August 2007. 96 Department for International Development, “Partnership Programme Agreements,” About DFID, 93 94 18 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 confirm that DFID is “easy to work with… and … in no way, [tries] to micro-manage the projects they fund.”97 DFID’s concept of genuine co-operative partnerships has extended, therefore, beyond recipient countries to include other organisations which have a stake in reducing global poverty. Aid classed as humanitarian relief, usually provided in response to a natural emergency, has seen no discernible pattern in the last two decades but has fluctuated considerably year-by-year, which is unsurprising given its nature. As such, ANOVA analysis found no significant difference between policies of the two government. Likewise, there has been no significant difference in the proportion of aid spent on debt relief since 1997. However if the data were to be extended to include the following year’s figures, there would, one would expect, be a significant increase in debt relief due to the accord signed by the UK at the Gleneagles G8 Conference pledging amnesty for the debts of 18 developing countries.98 H4: AID CONDITIONALITY The fourth question concerning DFID’s work raised earlier hypothesised a move from commercially-tied aid to aid conditional on political reform. This too was largely borne out by an examination of the policies pursued by the new department, and interviews with development observers. The first White Paper published by DFID,99 Britain’s first for more than two decades, pledged to outlaw the Aid and Trade Provision, the most obvious vestige of the previous commercial aims of aid, in a move that was almost universally welcomed. The one notable exception was the Confederation of British Industry100 – opposition that, one suspects, was not unappreciated by DFID as indicative of its new focus on poverty reduction. In spite of this, the White Paper retained the option for DFID to use “mixed credits” as long as there was a commitment to poverty reduction. The distinction between ATP and mixed credits was one that academics had perceived to be only nominal.101 However, in 2002, the International Development Bill passed after DFID’s second White Paper102 (2000), made all forms of tied aid illegal, apparently putting an end to the decades-old tradition of British firms’ profits being a factor in aid provision. Nevertheless, interviews with NGO officials provide anecdotal evidence that the realities of DFID programmes may not equate to the legislation passed. One official with a large aid organisation suggested that while there were no explicit commercial links, “habits… http://www.dfid.gov.uk/aboutdfid/DFIDwork/ppas/partnerprogagreements.asp. 97 Anonymous (British-based NGO official), interview by Alan Webster, July 2007. 98 BBC News, “Government defends G8 aid boost,” 9 Jul y, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4666743.stm. 99 Department for International Development, Eliminating World Poverty: Making Governance Work for the Poor, White Paper on International Development (London: The Stationery Office, 2006). 100 House of Commons, Select Committee on International Development, Parliamentary Debates, 14 May 1998 column 66. 101 Morrissey 1998. 102 Department for International Development, Eliminating World Poverty: Making Globalisation work for the Poor, White Paper on International Development (London: The Stationery Office, 2000). 19 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW informal agreements [between] ex-pats who know each other … and career ambitions” meant that DFID officials overseas usually granted contracts to British firms over local competitors.103 Official figures released by DFID confirmed this, showing that in 2004 and 2005 (the only years for which such data was collected), fewer than 27% of aid contracts awarded by DFID were to firms based in the recipient country.104 While it is possible to argue that recipient countries’ firms may not be able to manage projects whose budgets often run into seven- or eight-figures, DFID was also forced to reveal that in those same two years, only 5% of contracts worth less than £100,000 were even tendered competitively.105 Thus, it appears that the complete commercial untying of British aid that legislation attempted to bring about has yet to be fully implemented ‘on the ground’ in developing countries. The review of the development field’s current thinking posited a move in British policy from commercial to political conditionality, identifying the rise of ‘good governance’ as a recent dominant trend in the development sector. DFID has indeed broadly followed the lessons of good governance’s importance, but has taken a different approach than the asymmetric conditionality conceived by the literature review. A policy paper produced by DFID106 set out the department’s approach on conditionality, stating that it had moved away from specific policy conditions imposed on developing countries to fostering equal partnerships with those recipient countries that share its commitment to poverty reduction. This was a move that only occurred taken under the leadership of Hillary Benn (Secretary of State, October 2003 – July 2007). Before this time, DFID had imposed conditions ensuring “the ‘right sort’ of economic liberalisation”, resembling the policies of the Washington Consensus, according to one NGO official.107 Instead, under Benn, British policy moved to requiring three broad conditions of recipients’ commitment to poverty reduction, open systems of government and respect of citizens’ human rights.108 This was a move welcomed by development organisations who criticised other notions of good governance because “conditionality is still being driven through it” (Interview 2, August 2007). Instead, DFID has embraced a pragmatic approach, stipulating only the outcome desired, namely poverty reduction, and leaving it largely up to recipient countries to determine their own path. As part of DFID’s commitment to establishing genuine partnerships with recipients, Hillary Benn also introduced aid programmes that Anonymous, August 2007. Author’s calculations based on data from Hansard, 28 November, 2005. 105 Author’s calculations based on data from Hansard, 28 November, 2005. 106 Department for International Development, Partnerships for Poverty Reduction: Rethinking Conditionality (London: The Stationery Office, 2005). 107 Anonymous, August 2007. 108 Ibid. 103 104 20 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 were committed to last for at least ten years and stated contractual responsibilities for both recipient and donor (DFID, 2007).109 However, a report commissioned by DFID found that British officials in the field were unclear about the terms of such agreements, which were, it claimed, ambiguous and included specific policy requirements purported to no longer be used by DFID.110 In addition, the report found that there were only two countries where written agreement had been drawn up between DFID’s local offices and recipient governments. Again, DFID’s supposed progressive nature has failed to materialise in its dealings with recipient countries, and it appears that more time is needed for the central department’s message and priorities to be taken up by its staff overseas. The changes identified in this section portray a dramatically different aid policy than that which was inherited by New Labour in 1997. Aid is now systematically targeted towards the least-developed countries in the world; more and more is donated direct to governments able to spent funds in the manner which they find most appropriate, while less is spent on the projects and technical assistance found to have failed in the past. DFID has also set in motion the beginnings of a policy that will see genuine partnerships developed with recipient governments, no longer tainted with overly-prescriptive policy conditions. In short, British aid is now best suited to help improve the lives of the world’s poorest individuals and countries. CONCLUSIONS The issue of international development remains one of the most pressing areas for government action. The fact that more than one billion people live in abject poverty in a world of such wealth ought to shame every developed country’s government into action. However, development policies, and those relating to aid in particular, have generally failed to significantly evolve from those of the past. Despite the fall of the Berlin Wall and continued Western prosperity, many countries still fail to target their aid efforts at the poorest countries and fail to use the most efficient and beneficial aid. One notable exception has been the United Kingdom. Since 1997, the Department for International Development has implemented dramatic changes to Britain’s aid policy. The quantitative analysis performed in an earlier section demonstrated that it has pursued an aid policy that mirrors the current ‘best thinking’ in aid policy identified in previously. British aid has begun to be systematically targeted at the poorest countries, moving away from the geopolitical and colonial influences that, until recently, usurped human needs. It is also increasingly targeted directly at recipient countries’ government, away from the technical assistance so despised by both academics and NGOs. Contrary 109 110 Department for International Development, “Partnership Programme Agreements.” Department for International Development and Mokoro, 5-6. 21 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW to this paper’s hypothesis, DFID has actually increased the proportion of aid being spent on projects, despite the critical voices over their use as a tool for development. However, greater investigation found that DFID’s commitment to establishing partnerships with civil society had broadened to funding projects proposed and managed by NGOs committed to reducing poverty levels. DFID’s emphasis on partnerships went beyond NGOs, extending to recipient countries themselves. Official British policy has abandoned all forms of strict policy conditionality and embraced what appears to be a more equal standing with those developing countries whose governments have committed themselves to the concept of ‘good governance’ now favoured by the field of international development. However, DFID’s progress has not been perfect. The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have had deleterious consequences for aid spending by drawing considerable funds away from middle-income nations that are particularly vulnerable to relapsing into lowincome status. In addition, interviews with NGO officials revealed that policy conditionality and contract-awarding have been slow to reform to official policy, and are not yet truly progressive. This remains an area of deep concern and risks undermining much of DFID’s work and, as such, deserves further research to examine whether official policy has yet been implemented on the ground. Nonetheless, these criticisms should not detract from the considerable successes DFID has made in the last ten years, and it is deservedly named “one of the most progressive” agencies. 111 Aid cannot claim to be a panacea for development. Other issues, notably global trade, are vitally important to undoing generations of underdevelopment. Nevertheless, it has an important part to play. This paper has argued that worldwide reform of aid policy, emulating the progress made by DFID would help achieve what would be the most important achievement of the 21st Century – the eradication of global poverty. REFERENCES ActionAid. Real Aid 2: Making Technical Assistance Work. London: ActionAid, 2006. Alesina, Alberto, and David Dollar. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5, no.1. (2000): 33-63. Allen, Chris. “Britain’s Africa Policy: Ethical, or Ignorant?” Review of African Political Economy 77 (1998): 405-407. Barder, Owen. “Reforming Development Assistance: Lessons from the UK Experience,” Centre for Global Development Working Papers 70 (2005), http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/4371 (accessed 18 January 2009). 111 Young, 251. 22 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 Bauer, Peter. “Foreign Aid: Mend It or End It?” In Aid and Development in the South Pacific, edited by Peter Bauer, Savenaca Siwatibau, & Wolfgang Kasper, 3-18. Australia: Centre for Independent Studies, 1991. BBC News. “Government defends G8 aid boost,” http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4666743.stm (accessed 18 January 2009). Boone, Peter D. “Politics and the Effectiveness of Aid,” European Economic Review 40, no.2 (1996): 289-329. Burnell, Peter. “Introduction to Britain’s overseas aid: between idealism and selfinterest.” In Britain’s Overseas Aid since 1979: between idealism and self-interest, edited by Anuredha Bose and Peter Burnell, 1-31. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991. Burnside, Crag and David Dollar. “Aid, Policies and Growth,” The American Economic Review 90, no.4 (2000): 847-868. British Social Attitudes Survey. British Social Attitudes Data, http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE (accessed 18 January 2009). Byrd, Peter. “Foreign Policy and Overseas Aid.” In Britain’s Overseas Aid since 1979: between idealism and self-interest, edited by Anuredha Bose and Peter Burnell, 49-73. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 49-73. Canadian International Development Agency. “Making a Difference? External Views on Canada’s international impact,” Canadian Institute of International Affairs report 20694, https://idlbnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/123456789/29167/1/120694.pdf (accessed 18 January 2009). Castle, Barbara. The Castle Diaries 1964-1970. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1984. Castle, Barbara. Fighting All The Way. London: Macmillan, 1993. Chalker, Lynda. “Britain’s Role in the Multilateral Aid Agencies,” Development Policy Review 8, no.4 (1990): 355-365. Chalker, Lynda. “Britain’s Approach to Multilateral Aid,” Development Policy Review 12, no.3 (1994): 243-250. Crawford, Gordon. “Partnership or power? Deconstructing the ‘Partnership for Government Reform’ in Indonesia,” Third World Quarterly 24, no.1 (2003): 139159. Demske, Susan. “Trade liberalization: De facto neocolonialism in West Africa,” Georgetown Law Journal 86, no.1 (1997): 155-180. Department for International Development. Eliminating World Poverty: A Challenge for the 21st Century, White Paper on International Development. London: The Stationery Office, 1997. Department for International Development. Eliminating World Poverty: Making Globalisation Work for the Poor, White Paper on International Development. London: The Stationery Office, 2000. Department for International Development. Achieving the Millenium Development Goals: The Middle Income Countries – a strategy for DFID 2005-2008. London: The Stationery Office, 2004. 23 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Department for International Development. Partnerships for Poverty Reduction: Rethinking Conditionality. London: The Stationery Office, 2005. Department for International Development. Statistics on International Development 2006. London: The Stationery Office, 2006. Department for International Development. Eliminating World Poverty: Making Governance Work for the Poor, White Paper on International Development. London: The Stationery Office, 2006. Department for International Development. Partnership Programme Agreements. London: The Stationery Office, 2007. Department for International Development. Predictability. London: The Stationery Office, 2007. Department for International Development and Mokoro. DFID Conditionality in development assistance to partner governments. London: The Stationery Office, 2005. Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Online Statistics, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/50/17/5037721.htm (accessed January 18 2009). Djankov, Simeon, Jose Garcia-Montalvo and Marta Reynal-Querol. “Does Foreign Aid Help,” Cato Journal 26, no.1 (2006): 1-28. Domar, Evsey D. “Capital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment,” Econometrica 14 (1946): 137-147. Doornbos, Martin. “Good Governance: The Rise an Decline of a Policy Metaphor,” Journal of Development Studies 37, no.6 (2001): 93-108. Easterly, William. “The lost decades: Developing countries’ stagnation in despite of policy reform 1980-1998,” Journal of Economic Growth 6, no.2 (2001): 137-157. Easterly, William. The elusive quest for growth: economists’ adventures and misadventures in the tropics. London: MIT Press, 2002. Easterly, William and Ross Levine. “Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, no.4 (1997): 1203-1250. Easterly, William, Ross Levine and David Roodman. “New Data, New Doubts: A Comment on Burnside and Dollar’s ‘Aid, Polices and Growth’ (2000),” Centre for Global Development Working Papers 26 (2003), http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/2764 (accessed 18 January 2009). Easterly, William and Sergio Rebelo. “Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth – an empirical investigation,” Journal of Monetary Economics 32, no.3 (1993): 417-458. Ferguson, Clare. “A Review of UK Company Codes of Conduct,” Report for Social Development Division of the Department for International Development, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/sddcodes.pdf (accessed 18 January 2009). Friedman, Milton. Capital and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. Foreign and Commonwealth Office, “Britain’s Aid Policy: Some Recent Developments,” no. 335/90. London: HMSO, 1980. 24 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 Godfrey, Martin, Chan Sophal, Toshiyashu Kato, Long Vou Piseth, Pon Dorina, Tep Saravy, Tia Savora and So Sovannarith. “Technical Assistance and Capacity Development in an Aid-dependent Economy: The Experience of Cambodia,” World Development 30, no.3 (2002):355-373. Goodlad, Alastair. “The View from the Opposition Benches,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 195-201. Gould, Bill. “New Labour, new international development policy?” Third World Policy Review 20, no.1 (1998): iii-vi. Green, Lara and Donald Curtis. “Bangladesh: partnership of posture in aid for development?” Public Administration and Development 25, no.5 (2005): 389-398. Gronemeyer, Marianne. “Helping.” In The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, edited by Wolfgang Sachs, 53-69. London: Zed Books, 1992. Hain, Peter. The End of Foreign Policy?: British Interests, Global Linkages and Natural Limits. London: Fabian Society, 2001. House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, 20 February 1980 columns 464-465. House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, 5 November 1997 columns 315-321. House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, 28 November 2005 column 55W. House of Commons, Select Committee on International Development, Parliamentary Debates, 14 May 2002. Hansen, Henrik and Finn Tarp. “Aid Effectiveness Disputed,” Journal of International Development 12 (2000): 375-398. Harrod, Roy F. “An Essay in Dynamic Theory,” Economic Journal 49 (1939): 14-33. Hattori, Tomohisa. “Giving as a Mechanism of Consent: International Aid Organisations and the Ethical Hegemony of Capitalism,” International Relations 17, no.2 (2003): 153-173. Hewitt, Adrian. “British Aid: Policy and Practice,” ODI Review 2 (1978): 51-67. Hewitt, Adrian and Tony Killick. “The 1975 and 1997 White Papers Compared: Enriched Vision, Depleted Policies,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 185194. Hyam, Ronald. “Winds of Change: The Empire and Commonwealth.” In British Foreign Policy 1955 – 1964: contrasting opinions, edited by Wolfram Kaiser and Gillian Staerck, 190-208. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998. Kampfner, John. Robin Cook. London: Victor Gollancz, 1998. Killick, Tony. “Policy Autonomy and the History of British Aid to Africa,” Development Policy Review 23, no.6 (2005): 665-681. Knorr, Klaus. Power and Wealth: the Political Economy of International Power. London: Macmillan, 1973. Labour Party. New Labour: Because Britain Deserves Better. Labour Party: London, 1997. Lammersen, Frans, and Anthony Owen. “The Helsinki Arrangement: its impact on the provision of tied aid,” International Journal of Finance and Economics 6 (2001): 69-79. Lancaster, Carol. Foreign Aid; Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Policies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. 25 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Mavrotas, George, and Bazoumana Ouattara. “Aid disaggregation and the public sector in aid-recipient economies: Some evidence from Cote D’Ivoire,” Review Of Development Economics 10, no.3 (2006): 434-451. Maxwell, Simon, and Roger Riddell. “Conditionality or Contract: perspectives on partnership for development,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 257-268. McCourt, Willy. “British Aid After the Comprehensive Spending Review 2007: Where Next for Development Spending,” IPDM Discussion Paper 71, http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/research/publications/wp/dp/dp_wp7 1.htm (accessed 18 January 2009). Morrissey, Oliver. “The Commercialisation of Aid: Business Interests and the UK Aid Budget 1978 – 1988,” Development Policy Review 8, no.3 (1990): 301-322. Morrissey, Oliver. “An Evaluation of the Economic Effects of the Aid and Trade Provision,” Journal of Development Studies 28, no.1 (1991): 104-129. Morrissey, Oliver. “ATP is Dead: Long Live Mixed Credits,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 247-255. National Statistics. “Public Attitudes Towards Development,” http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/omnibus2005.pdf (accessed 18 January 2009). Overseas Development Administration. “Politics and Rural Change.” In Sector Appraisal Manual: Rural Development, 1-5. London: HMSO, 1980. Overseas Development Administration. UK Memorandum to the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. London: HMSO, 1982. Overseas Development Administration. The Lessons of Experience: Evaluation Work in ODA. London: HMSO, 1987. Overseas Development Administration. Economic and Social Research: Achievements 1992 – 1995; Strategy 1995 – 1980. London: HMSO, 1996. Overseas Development Ministry. The Work of the New Ministry. London: HMSO, 1965. Overseas Development Ministry, “Overseas Development: The Work of the Ministry of Overseas Development,” Factsheet no.1. London: HMSO, 1965. Overseas Development Ministry, “UK Figures on Aid,” Factsheet no.2. London: HMSO, 1965. Overseas Development Ministry, “International Aid Figures,” Factsheet no.3. London: HMSO, 1965. Overseas Development Ministry, “Colonial Development and Welfare,” Factsheet no.9. London: HMSO, 1965. Overseas Development Ministry. What is British Aid?: 67 Questions and Answers. London: HMSO, 1967. Overseas Development Ministry. ‘British Aid Overseas: An Introduction to the Aid Programme. London: HMSO, 1975. Porteus, Tom. “British government policy in sub-Saharan Africa under New Labour,” International Relations 81, no.2 (2005): 281-297. 26 VOL. 4, NO. 1 – SEPTEMBER 2008 Power, Marcus. “The Short cut to international development: representing Africa in New Britain,” Area 32, no.1 (2000): 91-100. Riddell, Roger C., and Anthony J. Bebbington. “Developing Country NGOs and Donor Governments,” Report to the Overseas Development Administration. London: Overseas Development Institute, 1995. Rostow, W.W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960. Selden Anthony. Blair. London: Simon and Schuster, 2004. Short, Clare. An Honourable Deception? London: Simon and Schuster, 2004. Shrimsley, Anthony. The First Hundred Days of Harold Wilson. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1965. Simensen, Jarle. “Writing the History of Development Aid’, Scandinavian Journal of History 32, no.2 (2007): 167-182. Slater, David, and Morag Bell. “Aid and the Geopolitica of the Post-Colonial: Critical Reflections on New Labour’s Overseas Development Strategy,” Development and Change 33, no.2 (2002): 335-360. Solow, Robert. “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” Review of Economics and Statistics 39 (1957): 312-320. Stiglitz, Joseph. “The Post Washington Consensus Consensus.” Speech presented to The Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Sao Paolo, Brazil, August 22, 2005, http://www2.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/download/speeches/IFIs/Post_ Washington_Consensus_Consensus.ppt (accessed 18 January 2009). Svensson, Jakob. “Why conditional aid does not work and what do to about it,” Journal of Development Economics 70, no.2 (2003): 381-402. Tomlinson, Jim. “The Commonwealth, the Balance of Payments and the Political of International Poverty: British Aid Policy 1958 – 1971,” Contemporary European History 12, no.4 (2003): 413-429. United Nations. Human Development Report 1997. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997. United Nations. Human Development Report 2006. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “What Is Good Governance?” http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/ProjectActivities/Ongoing/gg/governance.as p (accessed 18 January 2009). Vereker, John. “Blazing the Trail: Eight Years of Change in Handling International Development,” Development Policy Review 20, no.2 (2002): 133-140. Whaites, Alan. ‘The New UK White Paper on International Development: An NGO Perspective,” Journal of International Development 10 (1998): 203-213. Williams, Paul. British Foreign Policy Under New Labour 1997 – 2005. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. Willis, Katie. “Harnessing globalisation for development: reflections on the UK government’s White Paper,” Third World Planning Review 22, no.4 (2005): iii–vii. 27 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Wilson, Harold. The War on World Poverty: an appeal to the conscience of mankind. London: Victor Gollancz, 1953. Wilson, Harold. “Britain and World Peace.” In The New Britain - Labour’s Plan: Selected Speeches 1964, edited by Harold Wilson, 90-100. London: Penguin Books, 1964. Wilson, Harold. The Labour Government 1964 – 1970: a personal record. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1971. Wilson, Harold. The First Edwina Mountbatten Memorial Lecture. London: Edwina Mountbatten Papers, 1973. Wilson, Harold. Final Term: The Labour Government 1976 – 1979. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1979. Wilson, Harold. Memoirs 1916 – 1964: the making of a Prime Minister. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1986. Young, Ralph. “New Labour and international development: a research report,” Progress in Development Studies 1, no.3 (2001): 247-253. 28