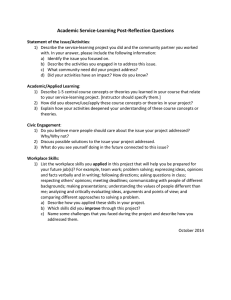

Developing a sense-of-place in middle school students through service learning :... by Patricia Jay Ingraham

advertisement