Agricultural educators time usage in different quality programs in seven... by Randall Dean Violett

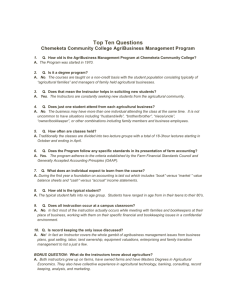

advertisement