An Evaluation of Local Laws Requiring Government Contractors Partners

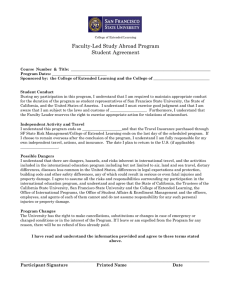

advertisement