AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

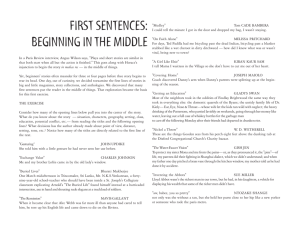

advertisement