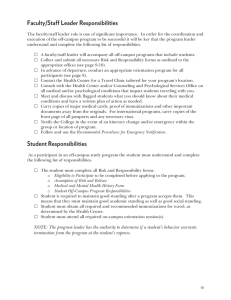

Institutional support of on-campus and off-campus nursing students

advertisement