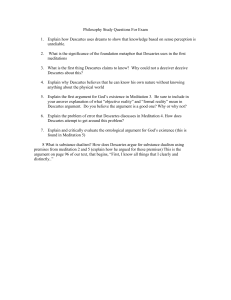

Meditations Rae Langton of

advertisement