Essential Services Committee Members

Essential Services Committee

Members

Susan Barthels, PEM

James Bartholomew

Lewis “Tres” Brooke, III, BA, MSA

Lynette Bush, RN, BSN

*Leon Conklin, BBL, CCP, L-RT

Daniel Farrow, EMT-P

Chris Fortin, BS, BSN, MHAS

Teresa German

Kim Greenwald

Debra Guy, RN

Mary Ann Hyde, RN, BSN, MSN

Mark Iverson

Laura Kuenzer, RS

Jon Kuyten

Beverly Mihalko, MPH, MT, CIC, CHSP

Katie Sims

Cathy Thompson

Kent County Emergency Management

Professional Med Team, Inc.

Comprehensive Emergency Management Associates, Inc

Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital

Mercy Health Partners

Mecosta County EMS

North Ottawa Community Hospital

North Ottawa Community Hospital

Saint Mary’s Health Care

Zeeland Community Hospital

Mecosta County Medical Center

Saint Mary’s Health Care

Spectrum Health Kelsey and United Hospital

Holland Hospital

Davenport University

Spectrum Health Reed City Hospital

Michigan Medical Patient Care

*indicates committee chair

Objectives

List essential hospital services to be maintained regionally during a pandemic.

List essential non-hospital services to be maintained regionally during a pandemic.

Develop a contrasting list of non-essential health care services that will be curtailed in hospitals and in non-hospital settings.

Develop a list of support services (e.g., logistics, utilities, supply chain management) needed to support all essential services.

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 1

Assumptions

1) Staff available to support the essential services at the sacrifice of non-essential services.

2) Hospital and community infrastructure will be available (power, fuel, water, waste management…) and intact.

3) Site protection and security in place.

4) Intact patient transport system.

5) Families will provide care at home if no room at hospital.

6) No other concurrent disasters.

7) Economy remains viable (payment and reimbursement, currency).

8) Warning of pandemic will provide time to prepare and mobilize resources,

9) Altered standards of care will be consistent for the Region.

10) Incident Command structures will be implemented.

Background

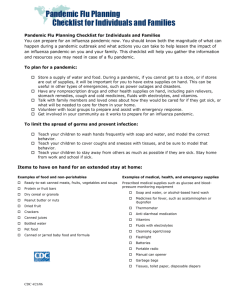

Essential services for hospitals and health care during a pandemic have a history dating back to at least the Great Pandemic of 1918

1

. Pictures are frequently used to demonstrate the way gymnasiums and other gathering locations were converted to care centers to meet the needs of those afflicted with “La Grippe”.

Recent evidence of similar issues was demonstrated during the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome

(SARS) outbreak earlier in this century. Hospitals experienced a sudden influx of patients and “worried well” who sought treatment for this condition. Toronto hospitals were forced to turn away patients because of lack of available beds

2

.

Even more recently, the impact that the novel H1N1 virus has had on health care in those cities hardest hit has helped to drive home the point that our health care system does not have an overabundance of beds or available staff to care for the ill.

The Process

Several factors have been identified as noteworthy by this subcommittee related to a health care response to a pandemic influenza. Just-in-time ordering of materials, current staffing models, and processes to minimize the economic drain on the health care organizations will be of concern if the pandemic escalates.

Public perception of the role health care organizations play in the care of sick and injured patients will also

1

Barry, John M, (2004) The Great Influenza . New York: Penguin Books

2

University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics Pandemic Influenza Working Group (2005) Stand on

Guard for Thee – Ethical Considerations in Preparedness Planning for Pandemic Influenza . A report of the

Bioethics Work Group

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 2

need to be assessed. Likewise, unless a gubernatorial or presidential declaration is made allowing for alterations to be made in the health care system, governmental requirements will dictate how the health care organizations will respond.

The current method of maintaining inventories of supplies and equipment in health care organizations limits the amount of available inventories to those needed just-in-time to allow for improved financial performance. Likewise, most organizations are staffed to meet the “average daily census”, which allows for very little fluctuation in the number of associates reporting for work on any given day. That also means there are very few ‘casual’ employees who work relief and could be called back if the need arose due to a spike in census as would be expected with a virulent pandemic. Hospitals tend to run close to full all of the time, and they tend to maintain the amount of equipment necessary to meet the needs of that population with very little to spare.

Public perception of the role health care organizations play in everyday health is another potential issue. A significant percentage of the population sees the Emergency Department as the neighborhood doctor’s office, meaning they go there when medical care is needed. Additionally, it has become an expectation that health care providers will provide the absolute best care possible for any illness or injury presenting; and that there is room available for this treatment. Rationing of health care is not even a consideration for the average person. Likewise, being the mobile society that we are, the expectation is that if we are home or in some far away city, we will be afforded the same quality and quantity of care. A recent inquiry into the percentage of vacation homes in northern Michigan owned by someone living in the more populous regions of the Midwest demonstrates some surprising numbers – over 50% of the people who own vacation homes travel there from the Greater Chicago, Indianapolis, or Detroit metroplexes

3

.

Another public perception is that of staffing health care facilities. Very few people even consider the possibility that a nurse or doctor would not go to work if the needs of the health care organization demanded their services. A model presented by the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) suggests a ‘no show’ rate of nearly 40% due to illness or family needs

4

.

Government expectations for health care organizations will provide some unique challenges in the event of a pandemic, including continuity of operations planning, utilization of the Strategic National Stockpile

(SNS), and alternative staffing models. Additionally, space to provide the needed care is also closely governed to assure enough to meet the needs of the average use, but nowhere near enough to meet the needs of a significant spike as might be observed during a pandemic.

Supporting Documents

The lists below outline some of the essential services determined by our study group as essential as well as those that should probably not be offered during the height of a pandemic cycle.

3

4

Personal correspondence with Chambers of Commerce in several northern Michigan communities (2009)

CDC Pandemic Severity Index (2009) Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Table One

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 3

Essential Services required for the hospital

Supply Management

HIM/Med Records

Imaging

Lab

Trauma Services - Destination

Infection Control

Emergency Medicine Services

Respiratory Therapy/Ventilation – viability determination

Equipment /Bio Med

OB Labor & Delivery

Surgery – emergent only

Critical Care – will likely be expanded

Food & Nutrition

Pharmacy

Laundry (shared vs. solo) – what are area hospital capabilities?

Admitting – communication element across the region (patient tracking)

Plant Operations/Utilities

Housekeeping

Social Work/Pastoral Care

Staffing/Human Resources

Accounting

Security

Morgue – temporary only

Information Technology System

Education

Communications

Non-Hospital services, but essential to mitigation of a pandemic

Home Health

Fire and EMS role in non-hospital care

Spiritual Care

Behavioral Medicine

Mortuary Services

Vaccinations – move to Public Health

Acute Care Site (may include Palliative Care)

Physician Practices

Radiation Oncology

Long Term Care/Skilled Nursing and Rehab Services

Home Vent Services

Dialysis

Outpatient Clinic

Infusion therapy

Wound care

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 4

Services no longer offered at the hospital

Elective Surgery/Procedures

Outpatient Services (Imaging, lab, rehab services PT, OT, chemical, substance)

Preventative Services (Routine physicals and well child visits)

Public Meetings

Non-emergent ED Services (non-life threatening)

Observation Patients (24-hour stay)

Support Services required, not necessarily on site

Emergency Operations Center / Joint Information Center (public information)

Courier

Trucking

Transportation Services (patients, staff & supplies)

Resource Management (fuel, maintenance, etc.)

211 services

Public Education

EMS

Waste Management (general and medical)

Public Utility (water, sewer, roads)

Public Safety (law enforcement, fire, 911 services)

Staff Procurement

Services for Special Needs Populations (daycare, eldercare, pet care, staff housing)

Pharmacy Services

Legal Services

Finance

Printing and Publishing

Communications

Information Technology Services

Morgue

The Conclusion

Several plans have been developed over the past few decades to try and deal with a response to a health care crisis. Beginning in the early 1960s with concern of a nuclear war, efforts to bolster training and supplies have continued to evolve. It was considered “patriotic” to be part of a Civil Defense organization with the intent of developing shelters and supplies to outlast a potential nuclear holocaust. This trend lost interest as the Vietnam War wound down, but was rekindled a bit in the late 1980s with the new threats posed by the Soviet Union. As life in the US and other wealthier parts of the world seemed to improve, interest in civilian preparation and planning for disasters fell by the wayside. Some organizations, like the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, continued to develop plans for responding to public health emergencies, whether naturally occurring or man-made. These efforts were put to the test on September

11,2001. Suddenly, it became very clear that we were no longer the isolated and protected nation we had been. The impact of this event, followed shortly by the SARS scare and Hurricane Katrina solidified the notion that although a Federal response may be of great assistance, it would not necessarily be immediately obtained.

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 5

Efforts need to be focused on development of more local responses for any type of incident, but with the knowledge that the Federal response would occur as soon as it was feasible. Efforts need to be coordinated, with all agencies utilizing a common terminology to avoid miscommunication and deployment of unneeded assets. This was the foundation for the National Response Plan. As has been stated many times, all incidents will begin and end locally. To that end, planning has to consider appropriate utilization of local assets as requests would go out for state and federal assets.

The scope of this chapter is on the Essential Services that need to be provided by health care organizations during a pandemic, but also on the accompanying surge of patients, both those ill and those who are afraid that they may become ill. As stated in the beginning of this chapter, one of the premises for health care today is that there is enough supplies and equipment to care for the number of patients normally expected to enter the health care system during the various seasons of the year. A busy seasonal flu season may stretch the resources of most health care organizations; and that may be affecting a whopping 5 percent of the population! Calculations presented by the CDC in their FluSurge model suggest that in a moderate pandemic with attack rates of 30 percent, at least 15 percent would need hospitalization

5

. This attack rate has to include health care workers and their families, which will also stress the ability of health care organizations to provide the customary care. An effort has been undertaken to assess what are the essential services provided by the hospitals, and what could be done creatively to limit the number of workers needed on site, but also the services that must be offered. As has been suggested by the pre-hospital planning group, the scale of response will necessarily change as the severity of the pandemic changes. Early planning for limiting non-essential services and creatively using available beds to meet the increased need will go a long way toward meeting the demands of a concerned public.

In the event of a need to determine essential services, we are suggesting a look at the needs of those most critical and working backwards, as well as looking at what could not be provided somewhere else. Critically ill patients may be the first to be considered by some, but in reality, it may be wiser to look at those who have the best opportunity for survival. Complicated obstetrical and those requiring urgent or emergent surgeries will need beds, but so will those who need prolonged ventilation with oxygen supplied by ventilators.

As is evident from the referenced tables, the services needed to provide care are complex. Couple that with the anticipated surge, and things will get very complicated very quickly. A very proactive response by the leaders of the health care organization will be required to effectively maintain a reasonable level of care.

The final aspect of essential services needs to focus on surge from within and outside the normal service area. Obviously all services will be stretched to the extreme limits, and with limited manpower, this will add to the struggles faced by caregivers. Development of a strong program of Acute Care Sites (ACS) may be effective in blunting the impact of limited availability of care due to the overcrowding of the hospitals.

Locations and available resources to mitigate this need are paramount to the success of this effort.

Preplanning at the community level and between local health care organizations to assure that needed equipment and personnel are available is the key to this success.

5

CDC Case Fatality Ratios Index (2009) Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Figure Four

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 6

Putting this entire piece together requires one final thought: effective triaging of patients to assure patients are placed appropriately for the level of care that they need in the location that is most appropriate for their care. A recommendation for determination of where to place patients would follow the same basic triage utilized in the pre-hospital setting – highest priority patients get the hospital beds, those less serious go to the ACS, and those who require minimal care or those not expected to survive get the least amount of health care resources.

In order for this plan to be effective, a great deal of coordination and cooperation are essential. The health care providers will require support from the staffing office as well as the pre-hospital triage group to assure appropriate patient placement, the ethics group to determine who gets care as well as how that care is provided, and the legal group to be sure the letter of the law is followed.

References

Determination of the severity of the pandemic will also aid in developing criteria for surge-based responses. The following table was developed by the Pre-Hospital Care Committee as a guide to effectively managing the pre-hospital response. This also has application in forecasting the degree to which health care will need to ramp up their response.

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 7

Situation

Hospital Status

Pre-ED Triage

For more detail on Pre-ED

Triage matrix see the Pre-

ED Committee Report

LEVEL A

Pandemic outbreak in North America.

Human

Transmissibility demonstrated

Standard Operating

Procedures

LEVEL B

Pandemic outbreak identified in Region 6

Anticipate cancellation of elective procedures

& non-emergent procedure

LEVEL C

911

Communications, and/or pre-hospital response systems, and/or hospitals AT

OR NEAR

CAPACITY.

Implement cancellation of nonemergent admissions and elective procedures. Transfer patients within region to hospitals with capacity.

LEVEL D

911

Communications, and/or pre-hospital response systems, and/or hospitals

BEYOND CAPACITY

LEVEL E

911

Communications, and/or pre-hospital response systems, and/or hospitals AND

SURGE SYSTEMS

BEYOND CAPACITY

Hospitals establish

Ambulatory Care

Centers

Level E intra-hospital and pre-ED triage criteria continuously reapplied to all patients.

Standard Operating

Procedures

Standard Operating

Procedures

Limited transport.

Transport to include to

ACS

Transport to ED vs

ACS. Home care options to include palliative care.

Staffing Hospital

For more detail on the

Staffing matrix see the

Staffing Committee Report

Standard Operating

Procedures

Standard Operating

Procedures

Activation of alternative care settings in hospital.

Implementation of altered staffing levels.

Maintain altered staffing levels

Staffing ACS

Standard Operating

Procedures

Standard Operating

Procedures

Standard Operating

Procedures

ACS activation and implementation.

Maintain ACS staffing levels.

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 8

The CDC has also provided some excellent resources to aid in predicting the severity of the pandemic and how various areas may be impacted.

This can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/tools/flusurge/

Another excellent reference is: http://www.flu.gov/plan/pdf/cikrpandemicinfluenzaguide.pdf

Several other reference articles are listed below:

Name Author Title Journal Date

Avian Flu

Pandemic.Shabonowitz.12p

Shabonowitz Avian Flu Pandemic - Flight of the Manuscript from

Healthcare worker? Geisinger Med

Ctr. pg.doc definitive care for critically ill Christian Definitive Care for the Critically Ill

During a Disaster: Capabilities and Limitations

Chest

Mass Medical Care with

Scarce resources

Health

Systems

Research

Mass Medical Care with Scarce

Resources. A Community

Planning Guide

AHRQ publication

Jun-08

May-08

Feb-07

Medical Resources Rubinson May-08 Definitive Care for the Critically Ill

During a Disaster: Medical

Resources for Surge Capacity

Chest

Project XTREME Report AHRQ -

Hanley

Project XTREME. Model for

Health Professionals' Cross-

Training for Mass Casualty

Respiratory Needs

AHRQ publication Mar-07

Summary from task force

05.08

Devereaux Summary of Suggestions From the Task Force for Mass Critical

Care Summit, Jan 2007

Chest May-08

Vent_guidelines_081 AARC publication May-08 American

Association of

Respiratory

Care

Guidelines for Acquisition of

Ventilators to Meet Demands for

Pandemic Flu and Mass Casualty

Incidents

Caring for the Community | preparing for an influenza pandemic 9