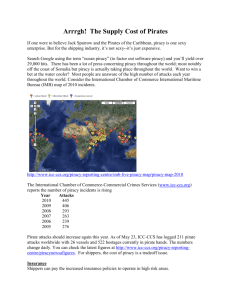

on Maritime Piracy UNOSAT Global Report

advertisement