NIGERIA

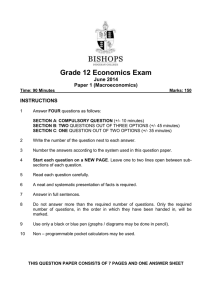

advertisement