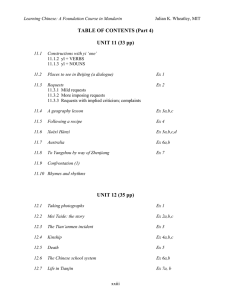

Unit 8

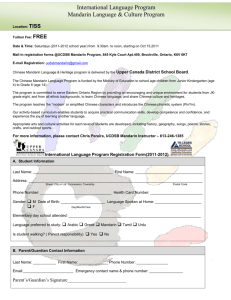

advertisement