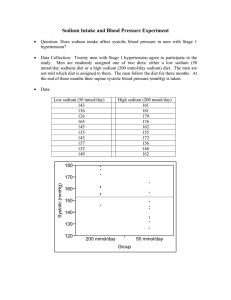

Sodium in drinking water and adolescent blood pressure

advertisement