Factors contributing to regular mall walking by Anna Cecelia Brewer

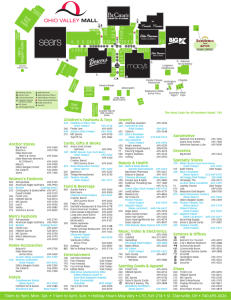

advertisement