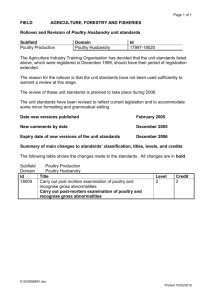

Review of Household Poultry Production on Bangladesh and India

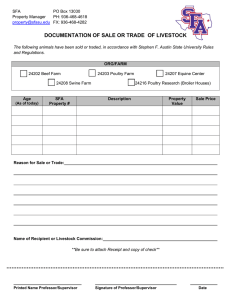

advertisement