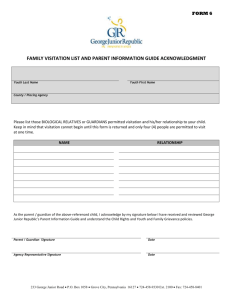

Visitation needs of families who have a member as a... by Susan Diane Simmons

advertisement