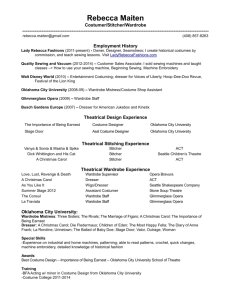

An analysis of the wardrobe content of Montana State University... showing wardrobe planning and sources

advertisement