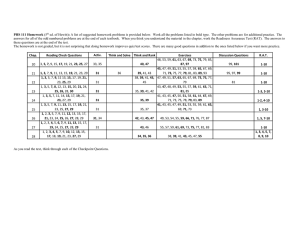

Reality Checks: A Comparative Analysis of Future Benefits

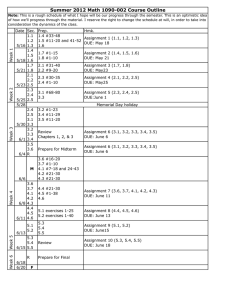

advertisement