Accrual Reversals, Earnings and Stock Returns Eric Allen Chad Larson

advertisement

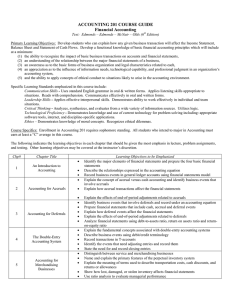

Accrual Reversals, Earnings and Stock Returns Eric Allen Chad Larson Richard Sloan Graham and Dodd (1934) Main Idea • Extreme accruals contain a disproportionately high concentration of extreme accrual estimation errors of the same sign • Accrual estimation errors must reverse in a subsequent period, causing earnings changes that correspond to the magnitude of the associated accrual reversal • Extreme accruals are associated with subsequent earnings changes of the opposite sign • Stock prices act as if investors do not fully anticipate these predictable accrual reversals and earnings changes 3 Contributions • Uses our knowledge of accrual accounting to document and explain economically and statistically significant properties of accruals and earnings. • Corroborates Sloan’s (1996) explanation for the ‘accrual anomaly’ [see competing explanations from Fairfield, Whisenant and Yohn (2001), Zach (2007), Kahn (2007), Ng (2005)]. • Provides an explanation for the robustness of the ‘accrual anomaly’ for inventory accruals [Thomas and Zhang (2002)]. We show that inventory accruals are more prone to extreme reversals. 5 Prior Research on Accrual Estimation Errors/Reversals • Dechow and Dichev (2002) • • Derive accrual estimation errors from regressions of accruals on past present and future cash flows Show that volatility of estimation errors positively related to absolute magnitude of accruals and negatively related to earnings persistence • Chan, Chan, Jegadeesh and Lakonishok (2006) • • Examine relation between magnitude of accruals and magnitude of subsequent special items Show that special items are unusually large and negative two and three years after accruals are unusually large and positive • Zach (2007) • • Firm-years with extreme accruals in one year are more likely to have extreme accruals of the same sign in the next year Weak evidence that abnormal returns are related to accrual reversals for high accruals, but inconsistent evidence for low accruals 6 Hypothesis Development • Properties of ‘good’ accruals: • • • They correctly anticipate future cash flows Their persistence depends on persistence of underlying economic growth of the business They have no direct consequences for the change in future earnings • Properties of accrual estimation errors: • • • They do not anticipate future cash flows They completely reverse in a subsequent period They temporarily inflate earnings today and temporarily deflate earnings tomorrow, causing a future earnings change that is opposite in sign and twice the magnitude of the error 7 Predictions P1: Accruals mean revert more rapidly than cash flows P2: Extreme accruals exhibit a disproportionately high rate of extreme accrual reversals (and corresponding earnings changes) P3: After controlling for accrual reversals, accruals are not negatively related to future earnings changes and future stock returns P4: Inventory write-downs are preceded by a disproportionately high frequency of extreme positive accruals 8 Samples • Main accruals sample ─ All observations in intersection of Compustat and CRSP with variables required to compute accruals between 1962 and 2006 ─ 149,685 firm-years • Inventory write-down sample ─ Subset of main sample with CIK numbers and fiscal years ending in 2001-2004 ─ 17,690 total firm-years ─ 1,886 firm-years reporting existence and amount of inventory write-down (hand-collected from Form 10-K filings using DirectEdgar) 9 Variable Measurement • Working capital accruals measured using the balance sheet approach (exclude depreciation) • Inventory write-downs reported as negative numbers (note that inventory write-downs should be charged to cost of goods sold, per EITF 96-9) • All financial variables deflated by average total assets • Abnormal stock returns measured using buyhold size-adjusted returns, including delisting adjustments, starting 4 months after FYE 10 Descriptive Statistics: Main Sample 11 Tests of P2: Proportion of Sample Belonging to Each Cash Flow Transition Cell 12 Tests of P2: Proportion of Sample Belonging to Each Accrual Transition Cell 13 Tests of P2: Proportion of Sample Belonging to Each Inventory Accrual Transition Cell 14 Change in Net Income for Accrual Transition Cells 15 Change in Net Income for Inventory Accrual Transition Cells 16 Abnormal Stock Returns for Accrual Transition Cells 17 Abnormal Stock Returns for Inventory Accrual Transition Cells 18 Tests of P1: Accruals Mean Revert More Rapidly Than Cash Flows 19 Tests of P2: Extreme Accruals Exhibit a Disproportionately High Rate of Extreme Accrual Reversals 20 Extreme Reversals Help to Explain Mean Reversion in Accruals 21 Tests of P3: After controlling for accrual reversals, accruals are no longer negatively related to future earnings changes 22 Tests of P3: After controlling for accrual reversals, accruals are no longer negatively related to future stock returns 23 Descriptive Statistics: Inventory Write-Down Sample 24 Tests of P4: Proportion of Inventory Write-Downs Belonging to Each Inventory Accrual Transition Cell 25 Tests of P4: Average Magnitude of Inventory Write-Downs Belonging to Each Inventory Accrual Transition Cell 26 Tests of P4: Regressions of Inventory Write-Downs on Previous Changes in Inventory 27 Conclusions 1. Extreme accruals are associated with a disproportionately high frequency of extreme reversals 2. These accrual reversals explain the predictable earnings changes and stock returns following extreme accruals (Sloan, 1996) 3. Reversals are particularly pronounced for inventory accruals, explaining the results in Thomas and Zhang (2002) 28 Implications • Accountants, auditors regulators and investors should pay more attention to extreme accruals • Accrual estimation errors may arise from: • active manipulation of accruals • distortions created by GAAP • delayed business and accounting responses to changes in economic conditions • Better identification of accrual estimation errors should facilitate improved forecasting of earnings changes and stock returns 29