2011 TRANSACTIONS TRANSFORMATIONS TRANSLATIONS

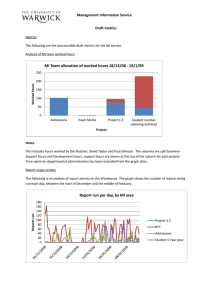

advertisement