An introductory inservice course in linguistics by Sharon Lee Showers Hoover

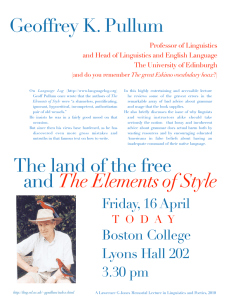

advertisement