Document 13499020

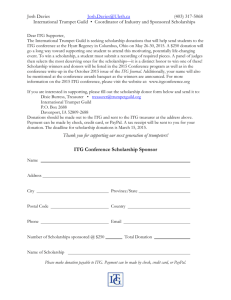

advertisement