An economic analysis of selected Montana State Water Conservation Board... by Elroy C McDermott

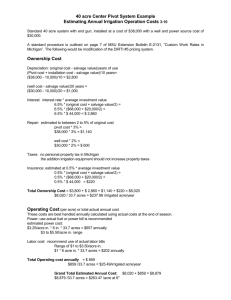

advertisement