Agricultural productivity change and wealth distribution in Hampshire County, Massachusetts (1700-1779)

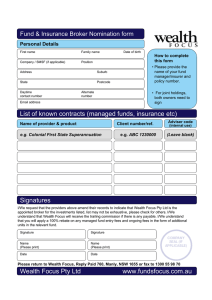

advertisement