3–1

MIT Department of Chemistry

5.74, Spring 2004: Introductory Quantum Mechanics II

Instructor: Prof. Robert Field

3–1

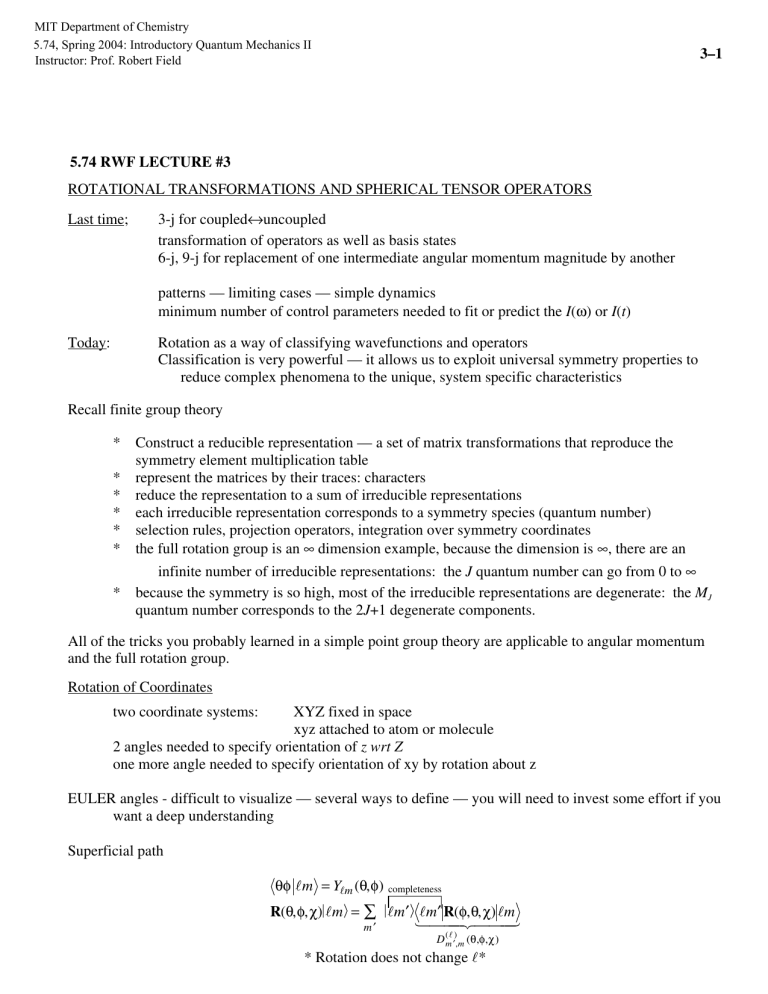

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3

ROTATIONAL TRANSFORMATIONS AND SPHERICAL TENSOR OPERATORS

Last time; 3-j for coupled

↔ uncoupled transformation of operators as well as basis states

6-j, 9-j for replacement of one intermediate angular momentum magnitude by another

Today: patterns — limiting cases — simple dynamics minimum number of control parameters needed to fit or predict the I (

ω

) or I ( t )

Rotation as a way of classifying wavefunctions and operators

Classification is very powerful — it allows us to exploit universal symmetry properties to reduce complex phenomena to the unique, system specific characteristics

Recall finite group theory

* Construct a reducible representation — a set of matrix transformations that reproduce the symmetry element multiplication table

* represent the matrices by their traces: characters

* reduce the representation to a sum of irreducible representations

* each irreducible representation corresponds to a symmetry species (quantum number)

* selection rules, projection operators, integration over symmetry coordinates

* the full rotation group is an

∞ dimension example, because the dimension is

∞

, there are an infinite number of irreducible representations: the J quantum number can go from 0 to

∞

* because the symmetry is so high, most of the irreducible representations are degenerate: the M

J quantum number corresponds to the 2 J +1 degenerate components.

All of the tricks you probably learned in a simple point group theory are applicable to angular momentum and the full rotation group.

Rotation of Coordinates two coordinate systems: XYZ fixed in space xyz attached to atom or molecule

2 angles needed to specify orientation of z wrt Z one more angle needed to specify orientation of xy by rotation about z

EULER angles - difficult to visualize — several ways to define — you will need to invest some effort if you want a deep understanding

Superficial path

θφ l m

=

Y l m

R

θ φ χ l m

=

∑

m ′ l m

′

1 m

′

4 444

D

( ) m m

θ φ χ

* Rotation does not change l

*

3

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3

[Non-lecture proof: (i) [ llll 2 , llll j

] = 0,

(ii) rotation operators have the form e i ll therefore: [ l 2 , R ] = 0 — no change in l

under rotation.] j

α

(rotate by

α angle about the ˆ j axis)

D

( ) m m is a (2 l

+1)

×

(2 l

+1) square matrix that specifies how the R (

φ,θ,χ

) rotation transforms | l m

⟩

.

3–2

Wigner Rotation matrix:

D l

′ this operates to left

(both bra and operator are complex conjugated)

= l m

′ ℜ ( ) l m operates to right

= l m

′ exp(

− i

φ ll z

)exp(

− i

θ ll y

)exp(

− i

χ ll z

) l m

3 successive rotations of | l m

⟩ in order

χ,θ,φ

= exp

( − i m

′ − χ ) l m m reduced rot. first matrix d l m m

∑

(

−

1) t t

[

( l + m

′

)!( l − m

′

)!( l + m )!( l − m )!

]

( l + m

′ − t )!( l − m

− t )! !( t

+ m

− m

′

)!

cos

θ

2

2 l + m m 2 t

sin

θ

2

2 − ′+ n t ranges over all integer values where the arguments of the factorials are not negative. d

( ) m m is real and has lots of useful properties

So now we know how to write the transformation under rotation of any angular momentum basis state.

l

, m are labels of an irreducible representation of the full rotation group.

Here is the wonderful part: the rotation matrices actually have the form of angular momentum basis functions!

D l m 0

(

, ,

) 2 l +

1

4

π

χ is irrelevant except

Y l m integer

(angular part of atomic orbital) for phase choice

D mJ

( φ θ χ ) [

(2 J

+

1)

]

, , JMK * sym. top wavefunction

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3 3–3

Not covered in Lecture

Suppose we have a matrix element of some operator A

JM A J M A

This is a number.

Rotate all 3 terms in the matrix element

[

JM R

− 1

]

RAR

− 1

[

R J M

]

=

A

If A can be expanded as a sum of terms that transform under rotation as angular momentum basis functions, then the integral is a sum of products of D(

φ,θ,χ

) matrices.

But the integral cannot depend on the specific values of

φ, θ, χ

.

This tells us that, if we can partition A into a sum of terms, each of which has the rotational transformation properties of an angular momentum basis state, we will be able to evaluate the angular part of the integral implied by the matrix element. This is actually how the Wigner-Eckart Theorem is derived.

Spherical tensor expansion is like a multipole expansion. Anything can be broken up into angular momentum-like parts, including what a laser writes onto a molecular sample.

A

( r ,

θ φ ) =

∑

a

J r Y

JM

( , ) (like the angular, radial separation of the hydrogen atom wavefunction) spherical tensor operators T q k a spherical tensor or rank k is a collection of 2 k + 1 operators that transform among each other under rotation as | l

= k m = q

⟩

Wigner-Eckart Theorem!

Notation: T q

NJM T

( ) q k ′ ′ ′

( 1 )

J

−

M

J k J ′

M q M ′

NJ T classification is wrt specific angular momentum

!! x,y,z are vector wrt L, J but not S , etc. proportionality constant:

“reduced matrix element” means some combination of the components of { A } that satisfies the commutation rules

[

[

J T

±

, q

( )

( ) q k

(

(

A

A

)

]

)

]

=

= q

[

T

(

( ) q k k

( A )

+ 1) − ( 1)

]

T q k

± 1

( A )

Alternatively, think of defining projection operators that project out of an arbitrary operator, symmetrylabeled operators.

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3

If A is a vector, like r r

= xi

ˆ + ˆ + zk L or S or J

3–4

T

0

( ) A z

T

( )

± 1

( ) m

2

− / (

A

X

± i A

Y

) if A is a second rank Cartesian tensor, like

xx xy xz

yx yy yz zx zy zz

nine components

(not the same as A

±

)

T

0

− / ( xx

+ yy

+ zz

)

T

0

T

(

±

1)

1

( ) i 2

−

/ ( xy

− yx

) e .

(

L L y

−

L L x

A m i / 2

{ ( yz

− zy

) ± i ( zx

− xz )

} e.g.

± i

2

{

( i h

L x

)

± i (

= i h

L z i h

L y

)

}

)

= h

2

{ ±

L x

+ i L y

} = ± h

L

2

±

T

2

±

1

T

2

±

2

= 6

−

1 2

{

2 zz

− xx

− yy

}

A m 1

2

{

( xz

− zx ) ± i ( yz

+ zy )

}

1

2

{

( xx

− yy ) ± i ( xy

+ yx )

} it is also possible to construct a 3

×

3 = 9 dimensional reducible spherical tensor out of two different vectors

3 x 3 = 9 reduces to 1 + 3 + 5

RANK: (0) (1) (2)

T

0 u v 3

− 1 2

= 3

− /

(

( u

1 v

−

1

− u

0 v

0

+ u

−

1 v

1

)

scalar product u v

+ u v

+ u v

)

T

0

T

( )

± 1 u v 2

−

/ ( u

1 v

− 1

+ u

− 1 v

1

) =

2

−

/

( u v

− u v

) u v 2

−

1 2 ( u

± v

− u

0 ± 1

)

=

1

2

[ ( u v

− u v

) m i

( y z z y

) ]

vector cross product

T

0 u v 6

− /

=

6

− /

T

( )

± 1

( , ) 2

− 1 /2

( u

1 v

−

1

+

2 u

0 v

0

+ u

−

1 v

1

)

(

2 u v

− u v

− u v

)

( u v

+ u v

±

1

)

T

( )

±

2

= m

1

2

[ u v

+ u v

± i

( y z z y

) ]

( , ) u

±

1 v

±

1

=

1

2

[ u v

− u v

± i

( u v

+ u v

) ]

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3

Transformations between SPACE and molecule fixed coordinate systems

A rotational wavefunction specifies the probability amplitude distribution of orientation of the molecule fixed axis system in the laboratory axis system. Origin of both coordinate systems is fixed at molecular center of mass.

We can express the relationship between LAB and molecule frame quantities. For example, radiation is specified in the LAB, but transition moments are tied to the molecule frame. The molecule

↔ radiation interaction

ε

·µ is a dot product between quantities specified in different coordinate systems. We must transform one of these into the coordinate system of the other.

“direction cosines”

3–5

P

LAB

ω = (φ,θ,χ) all 3 Euler angles inverse:

∑

q

D

Pq

ω

( ) molecule k q

( )

∑

P

D

Pq

D

Pq

( ) k

( )

= D

( )

− −

q

ω we know this from the form of D exp(– i J z

φ

)d(

θ) exp(– i J z

χ

) symmetric top wavefunction | J = k, M=–P,

Ω

= -q

⟩

⟨ω

| J

Ω

M

⟩

= [(2 J + 1)/8

π 2 ] 1/2 D

M

Ω

(

ω

)*

Thus the action of T A on | J

Ω

M

⟩

is an example of an uncoupled to coupled transformation and a matrix element of D is two such transformations

Ω D

Pq

( ) * J

′ ′

M

′

( 1)

M

−Ω [

(2 J

+

1 2 J

′ +

1)

]

J k J

′

J k J

′

q molecule

Ω′−

M P

LAB

3

(the order of the columns is rearranged from what we expect from vector coupling, but compatible with symmetry properties of 3–j) It is in form of W-E Theorem

5.74 RWF LECTURE #3

These are the direction cosine matrix elements!

For a laboratory frame

ε

(t) field polarized along the z-axis

H ( )

=

– T

1

P

=

0

( εε

( )

) ⋅

T

1 q

( )

=

– T

1

0

( εε

( )

)

1

∑

D q

=−

1

1

0 q

ω

T

1

(

µ) rotate molecule frame into space frame for a transition polarized along the molecule z-axis,

H ( )

= −ε

Z t D

1

00

ω µ z

.

0

J

H t J

′ ′

M

= −ε z

( )

µ z

(

−

1)

×

J

−

M

J

1

0

J

′ J

M

′ −Ω

1

0

P (

∆

M selection rule) q (

∆Ω

selection rule)

J (

−

1)

J

−Ω

J

′

Ω ′

3–6

× [

(2 J

+

1 2 J

′ +

1)

]

.

This result is based on the spherical harmonic addition theorem which is derived in A. R. Edmonds Angular

Momentum in Quantum Mechanics, page 62:

∫ 2

0

∫

0

∫ 2

0

π

D

( j

1

) m m

(

αβγ

) D

(

2 j

′

2

)

2

(

αβγ

) D

( j )

3

3 (

αβγ

) d

α

sin

β β γ

2

j

1 j

2 j

3

j

1

m

′

m

′

m

′

m

1 j

2 m

2 j

3

m

3