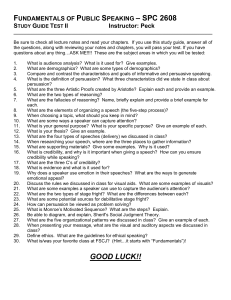

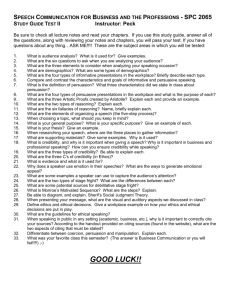

Source versus message cues in persuasion : the interaction of... comprehensibility

advertisement