L v. LAWRENCE WORLD

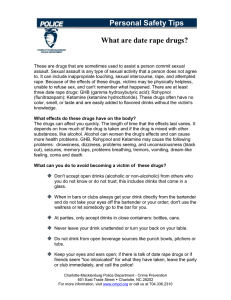

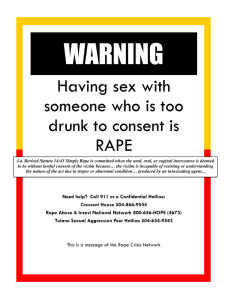

advertisement