Estrus synchronization in cattle and sheep using orally active progestogen

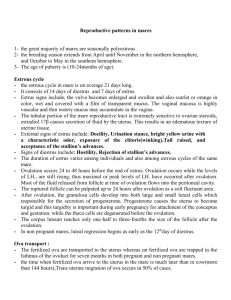

advertisement