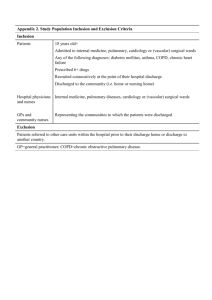

Psychiatric patient needs assessment as it pertains to discharge planning

advertisement