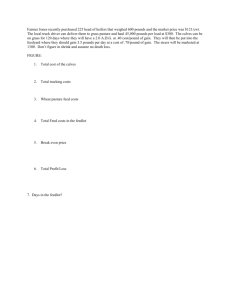

The feasibility of beef feeding cooperatives in Montana

advertisement