This is a case for the police : the Butte... by Jonathan Alan Axline

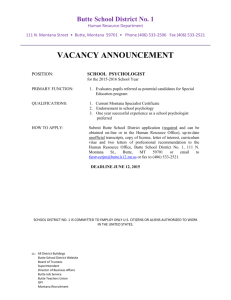

advertisement