Document 13478411

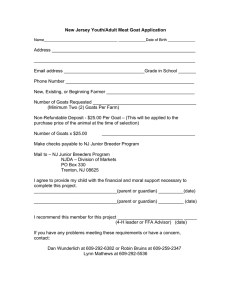

advertisement