Document 13475274

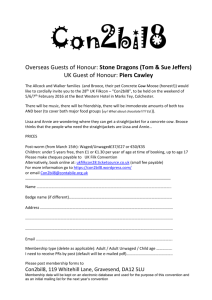

advertisement

Housekeeping English 223 – Week 7 “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work” “Not only has housework been imposed on women, but it has been transformed into a natural attribute of our female physique and personality, an internal need, an aspiration, supposedly coming from the depth of our female character. Housework had to be transformed into a natural attribute rather than be recognised as a social contract because from the beginning of capitals’ scheme for women this work was destined to be unwaged. Capital had to convince us that it is our natural, unavoidable and even fulfilling activity to make us accept our unwaged work” How natural is housework? “It takes at least twenty years of socialisation – day-to-day training, performed by an unwaged mother – to prepare a woman for this role, to convince her that children and husband are the best she can expect for from life” How do these quotes illustrate the idea of interpolation? • How does Fanon describe his experience of being interpolated as a negro? • How does Butler describe how people are interpolated as girls? • Can we think of how this occurs in some of the novels we’ve read thus far? “When I went to college, I majored in American literature, which was unusual then. But it meant that I was broadly exposed to nineteenth-century American literature. I became interested in the way that American writers used metaphoric language, starting with Emerson. When I entered the Ph.D. program, I started writing these metaphors down just to get the feeling of writing in that voice. After I finished my dissertation, I read through the stack of metaphors and they cohered in a way that I hadn’t expected. I could see that I had created something that implied much more. So I started writing Housekeeping, and the characters became important for me.” “For now we had to leave. I could not stay, and Sylvie would not stay with me. Now truly we were cast out to wander, and there was an end to housekeeping […] All this is fact. Fact explains nothing […] imagine Lucille in Boston, at a table in a restaurant, waiting for a friend. She is tastefully dressed – wearing, say, a tweed suit with an amber scarf at the throat to draw attention to the red in her darkening hair. Her water glass has left two-thirds of a ring on the table, and she works at competing the circle with her thumbnail. Sylvie and I do not flounce in through the door, smoothing the skirts of our oversized coats and combing our hair back with our fingers. We do not sit down at the table next to hers and empty our pockets in a small damp heap in the middle of the table, and sort out the gum wrappers and tickets tubs, and add up the coins and dollar bills, and laugh and add them up again. My mother, likewise, is not there, and my grandmother in her house slippers with her pigtail wagging, and my grandfather, with his hair combed flat against his brow, does not examine the menu with studious interest. We are nowhere in Boston. However Lucille may look, she will never find us there or any trace or sign. We pause nowhere in Boston, even to admire a store window. No one watching this woman smear her initials in the steam on her water glass with her first finger, or slip cellophane packets of oyster crackers into her handbag for the sea gulls, could know how her thoughts are thronged by our absence, or know how she does not watch, does not listen, does not wait, does not hope, and always for me and Sylvie” (219)