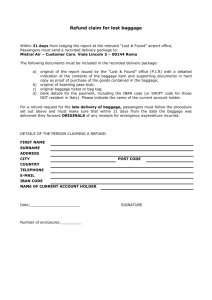

travellers’ checks contents

advertisement

Lawyers to the travel and leisure industry travellers’checks Autumn 2004 contents Insurance update 1 The future of consumer protection 3 Increase in fuel charges 4 IATA challenge to new passenger protection rights 4 New rules under the Montreal Convention 1999 5 Home or away... 7 Stop press 8 Corporate killing new law at last 8 Welcome to the autumn edition.... Regulation, regulation, regulation is the theme of our Insurance update From 14 January 2005, the Financial Services Authority ("FSA"), the UK's financial services regulator, will be responsible for regulating firms that carry out "general insurance business" as part of the implementation of the Insurance Mediation Directive by the United Kingdom. Autumn edition of Travellers' Checks. The travel industry is one of the most heavily regulated sectors in the UK and given the number of recent developments, we are dedicating a whole edition to update you in the areas of financial protection, security, insurance and employment law to name but a few. www.ngj.co.uk Following representations made by ABTA and others, the FSA has agreed that agents and operators selling travel insurance will not need to be regulated where insurance mediation activities are carried on in relation to "connected contracts of insurance". However, ABTA members will be subject to regulation in this area imposed by ABTA. In broad terms, a "connected contract of insurance" is a contract of insurance which: (1) is not a contract of long term insurance; (2) has a total duration (including rights to renewal) of 5 years or less; (3) has an annual premium (or the equivalent of an annual premium) of €500 or less; (4) covers the risk of: (a) breakdown, loss of or damage to, non-motor goods supplied by the provider; or (b) damage to, or loss of, baggage and other risks linked to travel booked with the provider. (5) does not cover any liability risks (except in the case of a contract which covers travel risks, where the travellers’checks cover is ancillary to the main cover provided by the contract); (6) is complementary to the service being provided by the provider; and (7) is of such a nature that the only information that a person requires in order to carry on one of the insurance mediation activities is the cover provided by the contract. This exemption applies to activities carried on by "a provider of relevant goods or services". Article 72B of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities) Order 2000 (inserted by SI 2003/1476 arts 2,11) defines a provider as: "a person who supplies non-motor goods [any goods which are not mechanically propelled road vehicles] or provides services related to travel in the course of carrying on a profession or business which does not otherwise consist of carrying on regulated activities." Good news for accommodation only suppliers Initially, the FSA maintained that the exclusion from FSA regulation was not available to accommodation only providers as they interpreted the phrase very restrictively, asserting that in order to qualify for the exemption, the travel arrangements must incorporate an element of transport from A to B. We challenged this on behalf of one of our accommodation only clients. 2 ABTA became involved and also negotiated in favour of the industry and we are pleased to say that the FSA have now given the provision a wider interpretation. The FSA have concluded that travel is not necessarily synonymous with transport but more widely refers to arrangements which necessitate travel. To put this in practical terms, the exemption would be available to persons (mainly but by no means wholly limited to travel agents and tour operators) whose regular business involves them in offering services involving travel as a package with insurance included. The FSA have said that they would expect that the regular business of a person to whom the exclusion applies would involve making arrangements for the purpose of travel, as opposed to making arrangements solely or predominantly for the purpose of merely providing the means of travel. As part of this "package", the FSA would expect the insurance to be in a standard form offered to all customers irrespective of whether or not they choose to make their own travel arrangements. The FSA have said that under this interpretation of "travel", a villa rental company may be regarded as covered by the exemption, as may any other person providing holiday accommodation. In the FSA's view, it should be possible to distinguish such a person from other providers of accommodation such as hotels on the basis that the former would be persons who can reasonably be regarded as providing services related to travel and who might be expected to offer travel insurance whilst the latter are not. However, readers should note that the sale of travel insurance by a travel agent on a stand alone basis (that is, other than with travel booked with the agent) is not excluded and is therefore the subject to FSA regulation. Autumn 2004 The future of consumer protection Last year we reported on the CAA's consultation process on the scope of consumer protection. The CAA's final advice to Government on the protection for flights and holidays in the future was published on 20 July 2004 and took into account comments from the industry and its response to a draft advice published earlier this year. The recommendations acknowledge that the ATOL system is becoming less effective because more and more people buy separate holiday components through the internet rather than as part of a package. These arrangements are unprotected, since they fall outside both the ATOL Regulations and the Package Travel Regulations but consumers do not realise that they are at risk of being stranded or losing money in the event of an insolvency. The number of these arrangements is on the increase. The CAA's research showed that last year in the UK 12 million leisure flights and holidays carried no protection, and the coverage of ATOL has declined from 98% of leisure travellers in 1997 to 70% in 2003. The CAA stress that this is of particular concern, given the number and complexity of travel company failures in recent times. The CAA's advice to Government is that there is now a serious problem in that holiday protection through ATOL is waning and the trend can only be reversed by a change in the law. The key recommendations are that: J J J The scope of travel protection should be extended to cover UK originating international return flights that are sold in the UK and paid in advance irrespective of the nationality of the airline. The protection should be extended to cover other facilities where these are sold with a flight, either in a package within the meaning of the Package Travel Regulations or by another supplier in conjunction with the flight. It would be preferable for the change to take place at European level, and the Government should use its influence within the European Commission to secure a change in the legislation. It may be a slow process (and there is a possibility of airline failures which will impact on the public in the interim) and the CAA recommends that the Government changes UK legislation without waiting for a change at European level. and exploring whether travel insurance policies might be expanded to cover airline failure in more cases and whether such policies could be sold at the point of sale. J Developing a code of conduct for airlines and travel companies which would specify the information to be passed to consumers on financial security. J Further research needs to be carried out into the method of providing protection through a common fund, bond or insurance instrument. If Government agrees with the CAA's conclusion that legislative change is required, the CAA will carry out a Regulatory Impact Assessment and consider the various funding methods in more detail. Travellers' Checks will, of course, be reporting on the Government's response. UK legislation may not be changed sufficiently quickly to deal with the increasing problem. The CAA has proposed some interim measures that might be adopted on a voluntary basis. The effectiveness of the interim measures would be a factor in determining the speed of changes in UK legislation. The voluntary measures proposed are comprehensive and reliable repatriation arrangements to cover flights sold on their own; airlines providing financial protection where a flight is sold by an airline in conjunction with other facilities 3 travellers’checks Increase in fuel charges In August 2004, British Airways and Virgin Atlantic increased the surcharge payable on all one-way long haul flights from £2.50 to £6.00 - resulting in an extra £12.00 charge in the cost of tickets for return flights. The increase was in response to a rise in fuel prices of 45% in the last 12 months. If operators wish to pass on additional costs to consumers by increasing the price of a pre-booked package holiday, they will need to consider the Guidance issued by the OFT on Unfair Terms In Booking Conditions In Holiday Brochures which we reported in our Spring 2004 edition: J J Regulation 11 of the Package Travel Regulations allows suppliers to surcharge after a holiday has been booked only in limited circumstances. Terms that provide for surcharges beyond those allowed by the Package Travel Regulations are highly likely to be considered unfair and void and of no effect by virtue of Regulation 11(1). The OFT is firmly of the view that terms providing for surcharges are void under the Package Travel Regulations unless they provide for both upwards and downward revision in the event of decreases in costs. J J Regulation 11(2) defines the circumstances in which surcharges are allowed and this extends to transport costs, including the cost of fuel. However, Regulation 11(3) provides that no increase may be made within a specified period, which may not be less than 30 days before departure. Regulation 11(3) also requires a supplier to absorb part of any increase, equivalent to at least 2% of the original cost of the holiday. IATA challenge to new passenger protection rights On 17 February 2005 new legislation will come into effect requiring airlines to increase denied boarding compensation (DBC) and also to compensate passengers where their flights have been delayed. The new law is set out in Regulation 261/2004, "on establishing common rules on compensation and assistance to passengers in the event of denied boarding and of cancellation or long delay of flights". The Regulation was approved on 17 February 2004 and comes into force next year. The United Kingdom and Ireland both voted against the Regulation. They and IATA were concerned that terrorist-related threats could require planes to be re-routed or cancelled. 4 In those circumstances the carrier would clearly not have been at fault. In addition, the lack of any defence for bad weather conditions would particularly affect operators in northern Scandinavia and the northern British Isles who might be required to refund the costs not only of their own flight, but also of a long haul flight where their flight formed part of a longer journey (i.e. interlining). Having failed to persuade the European Commission of the validity of its concerns, IATA launched legal proceedings in April of this year in the English High Court. Under EU law, IATA has no standing to challenge the Regulation directly in the European Court of Justice ("ECJ"), but is relying on the High Court's power to refer questions on the interpretation of EU law to the ECJ. IATA is seeking a declaration that the Regulation is unlawful. IATA has two legal grounds for its challenge. The first is that the Regulation allows airlines no defence against delays caused by matters outside their control such as bad weather or industrial action. Under the Montreal Convention, however, to which the European Community is a signatory, air carriers are not to be held liable for delays which are outside their control where they take all reasonable measures to avoid that delay. The Regulation will arguably put the Autumn 2004 European Community in breach of its commitments under the Convention. The second argument is that a potential defence which allowed carriers not to pay compensation where the cause of delay was outside their control, was removed from the draft Regulation by the EU Conciliation Committee. There appears to have been no justification for this removal given that the Council had suggested such measures and the European Parliament had raised no concerns to the defence. The High Court has now accepted these arguments and agreed to refer the matter to the ECJ. An Attorney General of the ECJ will give an Opinion on the case later this year, and the ECJ will publish its decision following its consideration of the Opinion. Given the date when the Regulation is to come into force it is likely that the Court will be asked to expedite its processes so that the industry is not forced to adapt to a Regulation that may be declared to be unlawful shortly after its implementation. If IATA is successful, it is likely that the Commission will propose a redraft of the Regulation which would then need to be approved - this would add at least a year's delay to the current timetable. IATA's claim and the position of the UK and Irish governments can at least in part be explained by the fact that the budget airlines (e.g. Ryanair and Easyjet) would have to increase their fares by proportionally more than the traditional airlines to fund the proposed compensation packages. Any pressure on fares currently charged by the successful UK and Irish budget airlines would almost certainly impact on their passenger numbers. New rules under the Montreal Convention 1999 The Montreal Convention (the "Convention") became effective on 28 June 2004, and has partly replaced the existing regime governing the liability of air carriers in relation to passengers, baggage and cargo as established under the 1929 Warsaw Convention, as amended at the Hague. not be held liable if any damage resulted from a flaw in the baggage itself. The objective of the Montreal Convention is to provide a greater level of financial protection for air passengers and their baggage, and for consignors of cargo. If the carrier admits the loss of a piece of checked baggage, or if it has not arrived within 21 days after it should have arrived, the passenger is in a position to rely on the contract of carriage, and all the rights they derive under it. Baggage Identification tag Under the Montreal Convention, the carrier must provide the passenger with a baggage identification tag for each piece of checked baggage. The "baggage check" of the earlier instruments in the Warsaw system has disappeared. Therefore, no record need be made of the weight of the baggage as liability is no longer based on weight. Destruction, loss or damage The carrier is liable for damages sustained in the case of destruction or loss of, or of damage to, checked baggage upon condition only that the event that caused the destruction, loss or damage took place on board the aircraft, or during any period within which the checked baggage was in the charge of the carrier. The carrier is not liable if and to the extent that the damage resulted from the inherent defect or quality of the baggage. Accordingly, a carrier should With respect to unchecked baggage, including personal items, a carrier will only be liable if the damage resulted from the fault of the carrier, its servants or agents. The convention does not specify what is required from the passenger to establish damage or loss to baggage. However, it is likely that carriers will continue to operate under a claim form system, as before. If a person accepts delivery of checked baggage without complaint this is prima facie evidence that it has been delivered in good condition. If there has been damage to the baggage, the person who has accepted the delivery must complain to the carrier after the discovery of damage and, at the latest, within 7 days from the date of receipt of the checked baggage. Delay In the case of delay, the complaint must be made at the latest within 21 days from the date on which the baggage or cargo was placed at the passenger's disposal. All complaints must be made in writing and, in the 5 travellers’checks case of damage, must be made within 7 days. If a passenger fails to make the complaint within the first 7 days, no action can be brought against the carrier, except where fraud is alleged against the carrier. Compensation for destruction, loss, damage or delay The liability of the carrier in the case of destruction, loss, damage or delay is limited to 1,000 special drawing rights ("SDRs") for each passenger. SDRs are an artificial currency unit created by the IMF in 1969. They are a measure of a country's reserve assets in the international monetary system. 1,000 SDRs is the equivalent of £800 - £850. This limit will apply unless the passenger has made, at the time of checking in the baggage, a special declaration of interest and has paid a supplementary sum. In that case, the carrier will be liable to pay a sum not exceeding the declared sum, unless they are able to prove that the sum was greater than the passenger's actual interest. Clearly, these limits will not apply if there is proof of intention or reckless misconduct on the part of the carrier. In the usual way, customers who wish to place valuable items in checked luggage will need to make a special declaration of interest. In the absence of this sort of declaration, any claim for loss or damage is limited to 1,000 SDRs. It is important to remember that the carrier will only be liable for unchecked baggage if either the carrier, its employees or agents are at fault. This is not the case with checked baggage and the level of responsibility becomes such that a carrier will be liable provided the destruction, loss or damage took place on board the aircraft or during any period within which the checked baggage was in their charge. Death and bodily injury Apart from the much higher limits on liability for baggage claims, this is the area where the Montreal Convention makes the most changes. There are no financial limits on liability for passenger injury or death. For damages up to 100,000 SDRs, the air carrier cannot seek to limit or exclude liability except, it seems, where there is contributory negligence. There is some doubt about this even now. If the claim is above 100,000 SDRs, a carrier can defend itself against the claim by providing that it was not negligent or otherwise at fault. If the carrier were to prove that: J 6 (a) such damage was not due to negligent or other wrongful act or omission of the carrier, its employees or agents; or J (b) such damage was solely due to negligent or other wrongful act or omission by a third party, the carrier could limit the amount it had to pay out in damages to the extent that they exceed the 100,000 SDRs. These limits do not prevent a Court from awarding a passenger recovery of his or her legal costs (costs of bringing the claim and interest). The limit set out above will not apply if the amount of damages (not including costs or interest) awarded by the Court is less than an amount which the carrier offered in writing within six months from the incident or six months from the commencement of the action, if that is later. This means that a passenger may not get payment of his Court costs or other litigation costs, including interest, if he recovers less than was previously offered by the carrier. There is also provision for advance payment to be made if a passenger is killed or injured. The carrier must make an advance payment, to cover immediate economic needs, within 15 days from the identification of the person entitled to compensation. In the event of a death, this advance payment should not be less than 16,000 SDRs. Limitation Period The limitation period for bringing claims for damages is two years from the date of arrival of the aircraft, or from the date on which the aircraft ought to have arrived. Autumn 2004 Home or away - can overseas employees sue their UK employer in cases of discrimination? In our last edition, Travellers' Checks reported on the case of Lawson v Serco Limited [2004] which held that the right to bring an unfair dismissal claim applies only to "employment in Britain". This would have prevented overseas staff employed by operators or agents from pursuing claims for termination of their employment. However, the position is under review as Mr Lawson has recently been granted qualified leave to appeal to the House of Lords. The case of Saggar v Ministry of Defence & Others [2004] examines the same issues in respect of sex and race discrimination claims. In this case, the Employment Appeal Tribunal (“EAT”) considered the jurisdiction of English employment tribunals to hear claims of sex and race discrimination brought by three army officers employed by the Ministry of Defence and stationed abroad. Under the sex and race discrimination legislation the test is different from that under the ERA 1996 - an employee can claim discrimination "unless he does his work wholly outside of Great Britain". We set out the issues which the EAT considered material to determining jurisdiction: J What is the relevant time? This test involves establishing the period during which it must be determined whether the applicant works wholly outside Great Britain. The EAT held that a tribunal must consider where the applicant was wholly or mainly working at the time of the alleged discrimination. The EAT stated there can be no discrimination at an establishment in Great Britain if the person being discriminated against either used to work in Great Britain but has not done so for many years, or was employed under a contract which contemplated he might be employed in Great Britain but in fact never was. J What is work? The next issue was what constituted "work" for the purpose of the phrase "employee does his work wholly outside Great Britain". The EAT directed tribunals to consider the following: (a) is the applicant required or expected under the contract to perform the task in question, or is the applicant simply permitted to do it, or do it in his or her own time? These principles will affect the travel and leisure industry. If employees who are predominantly based abroad return to the UK periodically for training, the English courts may have jurisdiction to hear any claim they may bring for sex and race discrimination. This is in contrast to the position for unfair dismissal claims where the same employees cannot bring a claim. Furthermore, a revised section 8 Race Relations Act is now in force and extends the protection of the Act in respect of discrimination on the grounds of "race or national or ethnic origin" to employees who work wholly outside Great Britain, where they are essentially British based workers posted to work for a UK company abroad. (b) what is the content of the work? and (c) what is its duration and its regularity? J Is there a minimum period for which the employee must be present in Great Britain? The EAT considered whether one day's work in Britain was sufficient to avoid a finding that an employee was working "wholly" outside Britain. The EAT referred to this as the "de minimis" principle. 7 travellers’checks Corporate killing - new law at last? Shortly after the 1997 Southall train crash Government announced plans to introduce a new offence of corporate killing. This complex issue has been brought to the fore again by manslaughter charges being dropped against certain key figures at Railtrack over the Hatfield rail crash in October 2000. organised fails to ensure the health and safety of persons employed in or affected by them. J J The Corporate Homicide Bill follows the recommendations of the Law Commission in 1997: J J J Corporate killing would be committed where the company's conduct in causing death fell far below what could be reasonably expected. The corporate offence should not require the risk to be obvious, nor would the prosecution need to prove that the defendant was capable of appreciating the risk. A death should be regarded as having been caused by the conduct of the company if it is caused by a management failure, so that the way in which the activities are managed or Who to contact For further information contact Cynthia Barbor or Laura Harcombe. cynthia.barbor@ngj.co.uk laura.harcombe@ngj.co.uk © Nicholson Graham & Jones 2004 8 Such a failure will be regarded as a cause of someone's death even if the immediate cause is the act or omission of an individual. Individuals within a company could still be liable for the offences of reckless killing and killing by gross carelessness as well as the company being liable for the offence of corporate killing. Government has attributed the delay in passing the new law to the complexities of drafting. However, pressure groups and union leaders have suggested the delay is due to the Government's reluctance to displease the business world. Current thinking is that the draft bill will be presented within the current session. Stop press Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP Travellers' Checks is pleased to announce that Nicholson Graham & Jones will be merging with US law firm Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP ("K&L") with effect from 1 January 2005. K&L, which has no existing presence in London, currently comprises approximately 800 lawyers in 10 US cities with its largest population of lawyers in Pittsburgh, Washington, New York and Boston. Additionally they have offices in Miami, Dallas, Harrisburg, Newark, Los Angeles and San Francisco. K&L serves a dynamic and growing clientele in regional, national and international markets which include representation of over half the Fortune 100. Comment It is good practice for all companies in the travel and leisure sector to implement a health and safety and due diligence policy to minimise risks to staff and customers. Nicholson Graham & Jones 110 Cannon Street, London EC4N 6AR 020 7648 9000 www.ngj.co.uk The contents of these notes have been gathered from various sources. You should take advice before acting on any material covered in Travellers’ Checks. The merged firm will be known as Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP.