UNDERSTANDING HOW CHEMISTRY HELPS CAN HELP: AN EXPERIMENTAL

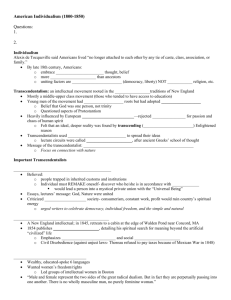

advertisement