–2 Viruses 19 Slide 1 of 34

advertisement

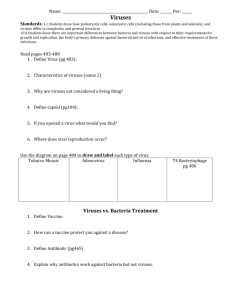

19–2 Viruses Slide 1 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses What Is a Virus? What Is a Virus? Virus comes from the Latin word for “poison.” Viruses are particles of nucleic acid, protein, and in some cases, lipids. Viruses can reproduce only by infecting living cells. Viruses differ widely in terms of size and structure. All viruses enter living cells and use the infected cell to produce more viruses. One of the first viruses to be discovered and named was the tobacco mosaic virus. Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall Slide 2 of 34 End Show 19–2 Viruses T4 Bacteriophage Head Tail sheath DNA What Is a Virus? Tobacco Mosaic Virus RNA Influenza Virus RNA Capsid Tail fiber Membrane envelope Capsid proteins Surface proteins Slide 3 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses What Is a Virus? Most viruses are so small, they can be seen only with the aid of a powerful electron microscope. A typical virus is composed of a core of DNA or RNA surrounded by a protein coat. A virus can have a few simple genes, or more than a hundred genes. A capsid is the virus’s protein coat, which includes proteins that enable a virus to enter a host cell. Capsid proteins bind to receptors on the cell surface and “trick” the cell into allowing it inside. Slide 4 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses What Is a Virus? Once inside, viral genes are expressed and the cell transcribes and translates them into viral capsid proteins. The host cell may makes copies of the virus, and be destroyed. Most viruses are highly specific to the cells they infect because they must bind precisely to proteins on the cell surface and then use the host’s genetic system. Viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages. Slide 5 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Viral Infection Once the virus is inside the host cell, two different processes may occur. • Some viruses replicate immediately, killing the host cell. • Others replicate, but do not kill the host cell immediately. Slide 6 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19-2 Viruses Viral Infection Bacteriophage injects DNA into bacterium Bacteriophage DNA forms a circle Lysogenic Infection Lytic Infection Slide 7 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Lytic Infection In a lytic infection, a virus enters a cell, makes copies of itself, and causes the cell to burst. First, the bacteriophage injects DNA into a bacterium. The bacteriophage DNA forms a circle. Slide 8 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 9 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 10 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 11 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Lysogenic Infection Other viruses cause lysogenic infections in which a host cell makes copies of the virus indefinitely. In a lysogenic infection, a virus integrates its DNA into the DNA of the host cell, and the viral genetic information replicates along with the host cell's DNA. Unlike lytic viral infections, lysogenic viruses do not lyse the host cell right away. Instead, a lysogenic virus remains inactive for a period of time. Slide 12 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection A lysogenic infection begins the same way as a lytic infection. The bacteriophage injects DNA into a bacterium. The bacteriophage DNA forms a circle. The viral DNA embedded in the host's DNA is called a prophage. Slide 13 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 14 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 15 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 16 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viral Infection Slide 17 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Retroviruses Retroviruses Retroviruses contain RNA as their genetic information. When retroviruses infect cells, they make a DNA copy of their RNA. This DNA is inserted into the DNA of the host cell. Retroviruses may remain dormant for varying lengths of time before becoming active, directing the production of new viruses, and causing the death of the host cell. Slide 18 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Retroviruses Retroviruses get their name from the fact that their genetic information is copied backward—from RNA to DNA. The viruses that cause AIDS and some types of cancer are retroviruses. Slide 19 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viruses and Living Cells Viruses and Living Cells Viruses must infect a living cell in order to grow and reproduce. They take advantage of the host’s respiration, nutrition, and all other functions of living things. Therefore, viruses can be considered parasites: they depend entirely on another living organism for existence, harming that organism in the process. Slide 20 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viruses and Living Cells Are Viruses Alive? Viruses have many of the characteristics of living things. After infecting living cells, viruses can reproduce, regulate gene expression, and even evolve. Viruses are at the borderline of living and nonliving things. Slide 21 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show 19–2 Viruses Viruses and Living Cells Because viruses are dependent on living things, it seems likely that viruses developed after living cells. The first viruses may have evolved from genetic material of living cells. Viruses have continued to evolve over billions of years. Slide 22 of 34 Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall End Show