DEFINING GRAMMAR: A CRITICAL PRIMER by Karen Marie Wilcox

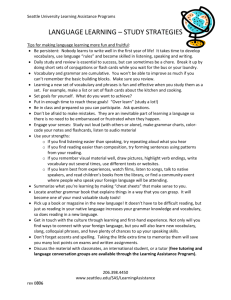

advertisement