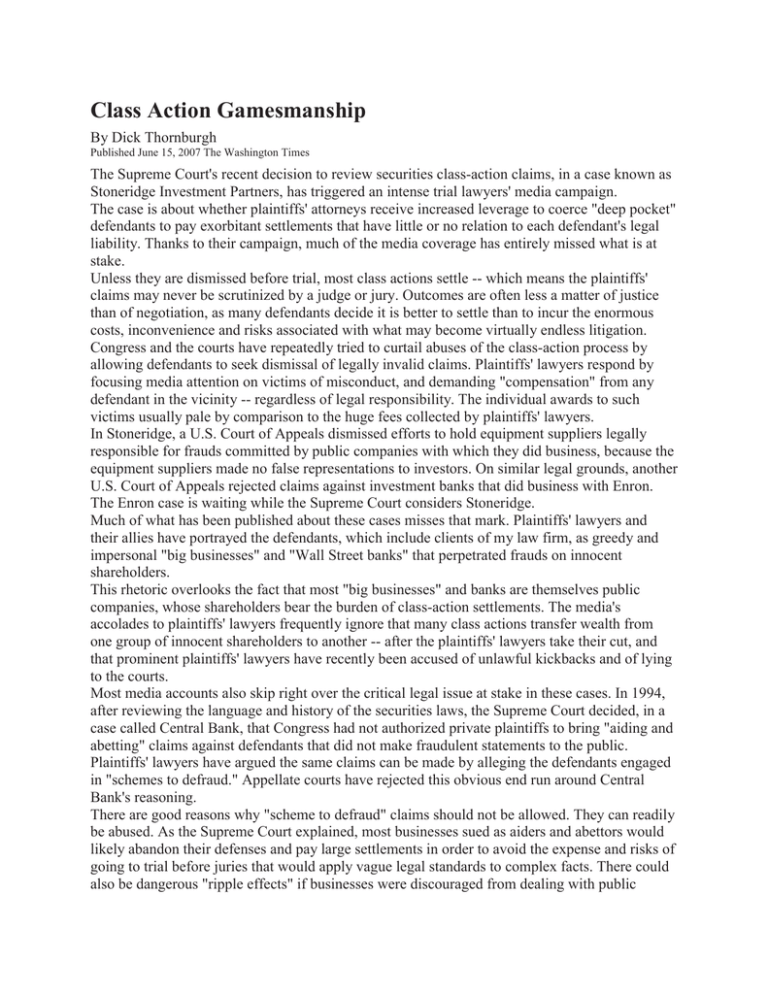

Class Action Gamesmanship

advertisement

Class Action Gamesmanship By Dick Thornburgh Published June 15, 2007 The Washington Times The Supreme Court's recent decision to review securities class-action claims, in a case known as Stoneridge Investment Partners, has triggered an intense trial lawyers' media campaign. The case is about whether plaintiffs' attorneys receive increased leverage to coerce "deep pocket" defendants to pay exorbitant settlements that have little or no relation to each defendant's legal liability. Thanks to their campaign, much of the media coverage has entirely missed what is at stake. Unless they are dismissed before trial, most class actions settle -- which means the plaintiffs' claims may never be scrutinized by a judge or jury. Outcomes are often less a matter of justice than of negotiation, as many defendants decide it is better to settle than to incur the enormous costs, inconvenience and risks associated with what may become virtually endless litigation. Congress and the courts have repeatedly tried to curtail abuses of the class-action process by allowing defendants to seek dismissal of legally invalid claims. Plaintiffs' lawyers respond by focusing media attention on victims of misconduct, and demanding "compensation" from any defendant in the vicinity -- regardless of legal responsibility. The individual awards to such victims usually pale by comparison to the huge fees collected by plaintiffs' lawyers. In Stoneridge, a U.S. Court of Appeals dismissed efforts to hold equipment suppliers legally responsible for frauds committed by public companies with which they did business, because the equipment suppliers made no false representations to investors. On similar legal grounds, another U.S. Court of Appeals rejected claims against investment banks that did business with Enron. The Enron case is waiting while the Supreme Court considers Stoneridge. Much of what has been published about these cases misses that mark. Plaintiffs' lawyers and their allies have portrayed the defendants, which include clients of my law firm, as greedy and impersonal "big businesses" and "Wall Street banks" that perpetrated frauds on innocent shareholders. This rhetoric overlooks the fact that most "big businesses" and banks are themselves public companies, whose shareholders bear the burden of class-action settlements. The media's accolades to plaintiffs' lawyers frequently ignore that many class actions transfer wealth from one group of innocent shareholders to another -- after the plaintiffs' lawyers take their cut, and that prominent plaintiffs' lawyers have recently been accused of unlawful kickbacks and of lying to the courts. Most media accounts also skip right over the critical legal issue at stake in these cases. In 1994, after reviewing the language and history of the securities laws, the Supreme Court decided, in a case called Central Bank, that Congress had not authorized private plaintiffs to bring "aiding and abetting" claims against defendants that did not make fraudulent statements to the public. Plaintiffs' lawyers have argued the same claims can be made by alleging the defendants engaged in "schemes to defraud." Appellate courts have rejected this obvious end run around Central Bank's reasoning. There are good reasons why "scheme to defraud" claims should not be allowed. They can readily be abused. As the Supreme Court explained, most businesses sued as aiders and abettors would likely abandon their defenses and pay large settlements in order to avoid the expense and risks of going to trial before juries that would apply vague legal standards to complex facts. There could also be dangerous "ripple effects" if businesses were discouraged from dealing with public companies because they might be sued as "aiders and abettors" of someone else's fraud. The Supreme Court's decision in Stoneridge could affect millions of people who are not parties to those lawsuits. Several recent studies have pointed out that class-action abuse poses a danger to our nation's competitiveness in a world economy. This has been a concern of mine since 1991 when, as attorney general, I led efforts to end lawsuit abuse, which threatens our economic growth and ability to create jobs by imposing a hidden tax on consumers and by making the United States a less attractive market in which to invest. As a former federal prosecutor and as a court-appointed examiner who spent years assessing the collapse of WorldCom, I believe those who break the law should be held to account. The Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission, acting under the broader legal authority Congress has given government enforcement authorities, have aggressively pursued firms and individuals who allegedly aided, abetted or otherwise collaborated with corporate executives accused of fraud. The issue is not whether to give a "pass" to those who engage in misconduct. What the court must decide is whether class action lawyers should be allowed to game the legal system to extort exorbitant settlements from businesses and professionals who deal with a public company that goes under. I respectfully submit they should not. Dick Thornburgh is a former U.S. attorney general and governor of Pennsylvania. He is counsel to Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP Copyright © 2007 The Washington Times LLC. This reprint does not constitute or imply any endorsement or sponsorship of any product, service, company or organization Visit our web site at http://www.washingtontimes.com -2-