VOL. 26, NO. 3

AUTUMN 2013

BENEFITS LAW

JOURNAL

From the Editor

Equitably Unfair: Supreme Court

Says Health Plan Document

Trumps Participant’s Request

to Split Legal Fees

I

t took the US Supreme Court three cases and more than a decade

to lay down the ERISA law on subrogation: It’s whatever the health

plan document says. Thus, the unanimous Supreme Court decision in

US Airways, Inc. v. McCutchen, 133 S.Ct. 1537, 2013, allows employers

to draft their health plans to provide that the plan gets first dibs on

any third-party recovery by a participant injured in an accident, even

before deducting the participant’s legal fees. Of course, employers

do not have to (and should not) impose this rule on their employees

injured in an accident when it would be harsh or foolish, but instead

should use McCutchen to reasonably and fairly draft and administer

subrogation clauses. And, beyond the health plan arena, McCutchen

strengthens the principle that in any dispute the plan document is king.

The facts of McCutchen show how the strict application of a right

of subrogation can be unfair. James McCutchen was in an awful

multivehicle auto accident. He incurred $66,866 in medical expenses, which were covered by his employer-sponsored health plan.

Although James estimated his total injury was north of $1 million, he

was only able to recover $10,000 from the driver who caused the accident (she was underinsured, and there was a fatality plus a number of

other serious injuries) plus an additional $100,000 from his own auto

insurer. After his lawyer’s 40 percent contingency fee, James was left

with $66,000. And the health plan wanted it all—plus an additional

$866 out of James’ own pocket. As Justice Kagan acknowledged,

From the Editor

James “would pay for the privilege of serving as [the plan’s] collection agent.” Adding insult to injury, it did not matter that the bulk of

James’s recovery came from the proceeds of an insurance policy paid

with his own money.

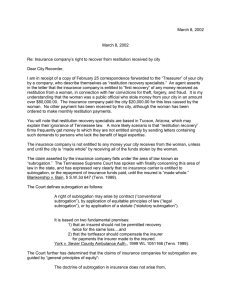

The health plan’s claim was based on two prior Supreme Court

cases, Great West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v. Knudson (534 U.S. 204,

2002) and Sereboff v. Mid Atlantic Medical Services (547 U.S. 356,

2006), holding that a plan’s claim for subrogation was “appropriate equitable relief” authorized by ERISA Section 502(a)(3). (Think

back to law school or perhaps when you were cramming for the

bar exam: Until the beginning of the last century, courts were

separated into law and equity, and subrogation was considered an

equitable remedy.) “Fine” said James, but if you can assert a Section

502(a)(3) equitable claim against me, I can counter with equitable

defenses. Specifically, James argued that the plan should not be

able to recover anything until he is “made whole” from all his losses

or, barring that, the plan should at least have to pay its share of

the legal costs in obtaining the recovery under the “common-fund”

doctrine. (Again, back to law school: Under the common-fund

doctrine, if two or more parties share a common asset—e.g., an insurance recovery—they must split the costs of obtaining that asset.)

The Court agreed that James ordinarily could use equitable defenses unless the plan document said he could not. The plan was viewed

as a contract between the participant and the plan fiduciaries, and

the parties could contractually “agree” that equitable defenses would

not apply. In an excellent turn of phrase destined to be repeatedly

quoted for decades, “[b]ut if the agreement governs, the agreement

governs.”

In this case, the plan stated that James was “required to reimburse

the plan for amounts paid for claims out of any monies recovered.”

Thus, the plan document trumped James’s right to assert any other

equitable defenses to the plan’s right of recovery. This should have

been the end of James’s day in court. However, five of the justices

found that the plan was vague because it was silent on the application

of attorney fees. Under the contract-is-the-contract approach, a vague

or incomplete subrogation provision may be reinterpreted by a court

to discern the parties’ intent. The case was sent back to the district

court to determine how to allocate legal fees.

This punt (cop-out?) back to the district court is particularly interesting because the lower court had already found the plan document

to be clear, ruling that James must pay. Perhaps the majority felt that

poor James was getting screwed by its opinion and, even though it

was fashioning a rule that could potentially short change many others,

wanted to give James a bone for his efforts.

BENEFITS LAW JOURNAL

2

VOL. 26, NO. 3, AUTUMN 2013

From the Editor

Where does this leave us, and what should employers and plaintiff lawyers do? If nothing else, the Court has left us a very clear

and simple rule: Employers are free to determine the scope of their

desired subrogation policy and set it out in the plan document. To

avoid instances of a sympathetic judge finding what’s clear to be

unclear, the plan language should be very specific. But just because

an employer can get first dibs on any recovery, that does not mean

that this is necessarily the best policy. In my practice I’ve found that

while every plan has a subrogation clause, employers are reasonable in applying this language. I’ve never seen a McCutchen-type

situation where the employer expected the employee to lose money

from its over aggressive subrogation claim. Indeed, I have a sneaky

feeling that even James and his employer would have worked

something out but for the fun their lawyers had arguing before the

Supreme Court.

With a subrogation provision, employers always benefit when their

employees recover after an accident. It is in the employer’s interest to

encourage, or at least not actively discourage, a participant victimized

in an accident from retaining counsel and suing. Also, a “plan-first”

subrogation clause pushes the participant-plaintiff to demand an

over-large recovery and not to settle for less, knowing that a more

modest recovery might put nothing in their pocket or, even worse,

cost them money. Thus, it behooves employers, the participantplaintiff, and his or her counsel to reach an accommodation with the

plan before bringing a suit as to how any monies recovered will be

divided. The lawyer should get his or her contingency fee. But, if the

recovery is large enough (compared to the medical costs and injury

suffered by the participant), the plan should be repaid in full, sans

legal fees.

More important than the simple and clear rule on subrogation is the

unanimous Court reemphasizing that, absent a contrary ERISA provision, employers are absolutely free to set the terms of their plans. In

other words, as long as it is legal, the plan document rules. Employers

should consider whether they wish to draft documents to foreclose

other forms of participant claims that go beyond what’s mandated by

ERISA. While this may seem cruel, in reality the freedom to set terms

encourages employers to provide benefits to employees and their

families.

David E. Morse

Editor-in-Chief

K & L Gates LLP

New York, NY

BENEFITS LAW JOURNAL

3

VOL. 26, NO. 3, AUTUMN 2013

Copyright © 2013 CCH Incorporated. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted from Benefits Law Journal Autumn 2013, Volume 26,

Number 3, pages 1–3, with permission from Aspen Publishers,

Wolters Kluwer Law & Business, New York, NY, 1-800-638-8437,

www.aspenpublishers.com