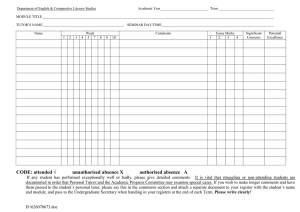

D&DA Award Scheme: Flexible Provision Projects 2004-5

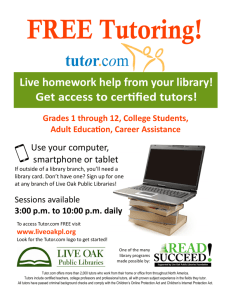

advertisement