Document 13458231

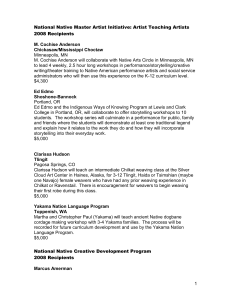

advertisement