The Park Lands of Isle au Haut: A Community Oral History

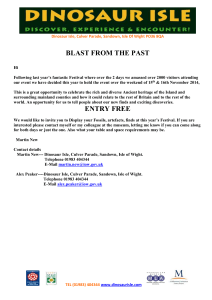

advertisement