A W R

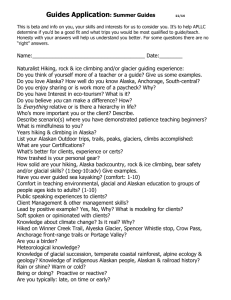

advertisement