Inventory Showrooms and Customer Migration in Information David Bell

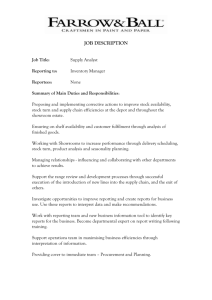

advertisement