Spring 2015 In Site

advertisement

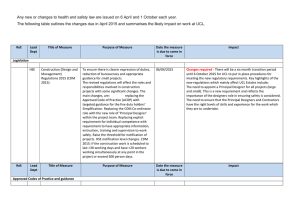

Spring 2015 Spring 2015 In Site Construction and Engineering By Kevin Greene, Mike Stewart, Inga Hall, Mary Lindsay & Daniel Clyne Welcome to the Spring 2015 edition of “In Site”. This edition covers the following topics: • CDM 2015 - a summary of the key changes to the health and safety regulatory framework with the coming into force of the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 on 6 April 2015; • An update on recent adjudication cases, including: o making fraudulent misrepresentations in seeking the nomination of an adjudicator in Eurocom Ltd v Siemens plc; o the decision in Broughton Brickwork Ltd v F Parkinson Ltd where an adjudicator’s decision was enforced even though he overlooked a document that would have altered his decision; and • The meaning of “construction operations” as interpreted in Savoye and Savoye v Spicers Ltd. For more information on any of these articles, or on any other issue relating to construction and engineering law, please contact any of the authors or your usual K&L Gates’ contact. Countdown to CDM 2015 The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 (“CDM 2015”) are due to come into force on 6 April 2015. They will replace the 2007 version of the CDM Regulations (“CDM 2007”), although projects begun before 6 April 2015 may be subject to limited transitional arrangements for the first 6 months. This note sets out what are to be the key changes to the current CDM regulatory regime. In a nutshell, the main expected changes are as follows: • There is to be a general widening of the scope and nature of CDM obligations and an increase in the number of projects to which obligations apply. • The role of CDM Co-ordinator is to be replaced with that of “principal designer”. • The competence assessment process is to be simplified. • Clients’ obligations and responsibilities are to be expanded. • Domestic clients are to be subject to the regulations for the first time. Dealing with each in turn: Widened scope of obligations - This will take effect in 3 key ways: • More projects will be subject to CDM 2015 than were subject to CDM 2007 - CDM 2015 will apply to all construction work in Great Britain (and certain offshore installations) and the previous exclusions for small or domestic (e.g residential) projects will be abolished. The only exclusion from CDM 2015 will be for the mineral extraction industry, although the associated process, storage facilities and the like will be covered by CDM 2015 (Regulation 2(1)). • All projects will now require a construction phase plan. Whilst under CDM 2007 only ‘notifiable’ projects required a construction phase plan, CDM 2015 will confer a duty Spring 2015 In Site on Clients to ensure that the contractor or principal contractor (if there is more than one contractor) draws up a construction phase plan before the construction phase begins on all works (Regulation 4(5)). • The HSE notification requirements will change - under CDM 2007, projects need to be notified if they are expected to last longer than 30 days or to involve more than 500 person-days of labour. Under CDM 2015, fewer projects are likely to be notifiable as the first ground for notifying will change to “longer than 30 days and have more than 20 workers simultaneously at any point in the project” (Regulation 6(1)). Replacement of CDM Co-ordinator with Principal Designer - Under CDM 2007, a CDM Co-ordinator needed to be appointed for all notifiable projects (i.e those likely to involve either more than 30 days of construction work or more than 500 person days of construction work). CDM 2015 will abolish the role of CDM Co-ordinator and replace it with the role of principal designer and will require a principal designer to be appointed on all projects (regardless of whether they are notifiable) which have more than one contractor (Regulation 5(1)). Although the principal designer will generally do much of the same work as was done by the CDM Co-ordinator, the intention of CDM 2015 is for the principal designer to have a greater influence over design by being responsible for pre-construction co-ordination (a criticism of the CDM Co-ordinator role being that they were often an external appointment, made later than ideal, whilst in contrast the principal designer is intended to be selected from an existing member of the design team and hence engaged from project inception). Simplifying of competence assessment - The detailed (and frequently criticised) competence obligations in CDM 2007 will be replaced with more general duties for (i) designers and contractors to have (and not to accept an appointment unless they have) the skills, knowledge and organisational ability to fulfil the role and (ii) persons responsible for appointing designers or contractors (which will include Clients) to take reasonable steps to satisfy themselves that the designer or contractor fulfils those conditions (Regulation 8). As to what will constitute “reasonable steps”, this will depend on the complexity of the project and the range and nature of the risks involved. Boosting the Client’s role and responsibilities - Regulation 4 will impose an on-going obligation on the Client to make suitable arrangements for managing a project to ensure that construction work is carried out safely throughout the duration of the project. The Client’s ability to delegate its health and safety obligations to others will be reduced (for example the duty to notify projects now rests on the Client rather than on the CDM Coordinator as was the case under CDM 2007), and it will be required to take reasonable steps to check that principal contractors and principal designers are complying with their duties. In addition, the Client’s ‘absolute’ obligations under CDM 2015 are expected to include: • appointing a principal designer and principal contractor before the construction phase begins (failing which it must fulfil those duties itself) (Regulation 5(1)); • ensuring that it provides pre-construction information to every contractor and designer (Regulation 4(4)); and • ensuring that the principal contractor prepares the pre-construction plan before construction starts and that the principal designer prepares the health and safety file at the end (Regulation 4(5)). 2 Spring 2015 In Site The scope of “Clients” to whom the Regulations apply will also be significantly expanded with “domestic clients” to be subject to the same obligations. Regulation 2 of CDM 2015 will define domestic clients as Clients “for whom a project is being carried out which is not in the course or furtherance of a business of that Client”. Although this means a homeowner extending their house will become a “Client” for CDM purposes, CDM 2015 seek to minimise the burden placed on such Clients by providing for an automatic transfer of the Client’s duties to the principal contractor or principal designer (Regulation 7(1)). Removal of ACoP - Another change which will come with CDM 2015 is that the current Approved Code of Practice (ACoP) will no longer have legal status. Instead of replacing the ACoP, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) will release guidance tailored towards each of the duty holders under the regulations, drafts of which are available via the HSE website. Transitional measures - As mentioned above, CDM 2015 will include transitional measures intended to aid the transition for those involved in works which begin before 6 April 2015. These measures will cover a variety of scenarios. Most notably, projects that start before 6 April 2015 and already have a CDM Co-ordinator appointed will have until 6 October 2015 to replace this appointment with a principal designer, unless the project finishes before that date. Such CDM Co-ordinators should comply with the duties contained in the transitional arrangements schedule (Schedule 4) to CDM 2015 rather than the duties of principal designers, until the new principal designer is appointed. Issues to consider in more detail as we move towards April will, therefore, include: • whether the transitional provisions will apply to an existing project and, if so, to get to grips with the transitional provisions, including issues surrounding any potential need to terminate the CDM Co-ordinator’s appointment when the transitional period comes to an end in October 2015; • considering who, within the design team, will be taking on the role of principal designer, ensuring their insurance will cover this enhanced role, and considering any conflict of interest issues; • in the context of domestic clients, ensuring that the ‘transfer’ of Client duties to either the principal contractor or principal designer is clearly documented; • getting to grips with the new notification requirements, and establishing how to comply with the simplified (but arguably less clear cut) information/training requirements which replace competency assessments; and • getting to grips with the draft HSE guidance as it is available. Adjudication update Eurocom Ltd v Siemens plc It is never easy to resist an action for enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision. Speed and certainty are central tenets to the adjudication mechanism provided by the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996. However, the judgment in the recent case of Eurocom Limited v Siemens PLC shows that the courts will not put enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision above basic legal principles. The dispute arose in relation to a sub-contract allowing for the installation of communication systems in the London Underground. Siemens terminated the subcontract in August 2012. A first adjudication took place and the decision made on 27 3 Spring 2015 In Site September 2012. That decision provided that a net sum was due from Eurocom to Siemens. Eurocom served a second notice of adjudication on 21 November 2013 and it was that adjudication that gave rise to these enforcement proceedings. In the enforcement proceedings the judge considered, amongst other things, whether appointment of the second adjudicator was valid. The adjudicator was appointed under the RICS’s nomination procedure. This required Knowles, acting for Eurocom, to complete a form in which it was asked to identify “any Adjudicators who would have a conflict of interest” in the case (who would not thereby be appointed). A number of adjudicators, the adjudicator in the first adjudication (who might very well and sensibly have been appointed as adjudicator in the second adjudication) and a firm of solicitors were listed in this section of the form. The form was not initially shared with Siemens. However, it subsequently came to light and it transpired that the adjudicators identified did not in fact have a conflict of interest in the case. Knowles accepted they did not “properly” answer the question asked by the RICS about conflicts of interest, but merely referred to people without any conflicts who they did not want to be appointed. Siemens’ primary case was as follows: • The application form sent to the RICS by Knowles seeking the appointment of an adjudicator misrepresented to the RICS that a number of individuals had a conflict of interest; • This was a false statement, made deliberately and/or recklessly by Knowles; and • A nomination based upon such a fraudulent misrepresentation is invalid and a nullity, such that the adjudicator has no jurisdiction. The Court decided the point as follows (at paragraph 65 of the judgment): “… there is a very strong prima facie case that [Knowles] deliberately or recklessly answered the question “Are there any Adjudicators who would have a conflict in this case?” falsely and that therefore he made a fraudulent representation to the RICS as the adjudicator nominating body.” The Court said that the consequence of this was as follows (at paragraph 75 of the judgment): “… I conclude that the fraudulent misrepresentation would invalidate the process of appointment and make the appointment a nullity so that the adjudicator would not have jurisdiction.” The Court also agreed with Siemens’ alternative case that the completion of the form gave rise to a breach of an implied term to act honestly. Here the Court referred to the judgment in Makers v Camden that there might be an implied term “by which the party seeking a nomination should not suborn the system of nomination”. Eurocom, through its advisors, had sought through fraudulent misrepresentation to influence the discretion to be applied by the appointing body, the RICS. Eurocom should not benefit from this benefit and the appointment of the adjudicator was invalid. The ramifications of this decision will be keenly monitored by the industry. 4 Spring 2015 In Site Broughton Brickwork Ltd v F Parkinson Ltd Material breaches of the rules of natural justice are a frequent ground for challenging an adjudicator’s decision on enforcement. Numerous cases have come before the courts which give us a sense of whether or not such a challenge is likely to be successful, a general theme of which being that the courts are generally reluctant to interfere with an adjudicator’s decision without strong grounds for doing so. The recent case of Broughton Brickwork Ltd v F Parkinson Ltd [2014] EWHC 4525 is in keeping with this general trend, but is interesting because the decision was enforced, despite the adjudicator overlooking a document which would have changed his decision. Why wasn’t this a natural justice breach, particularly as paragraph 17 of the Scheme for Construction Contracts (applicable in this case) states that the adjudicator “shall consider any relevant information submitted to him by any of the parties…”? The dispute concerned the contractor’s (F Parkinson’s) failure to pay the sum of £96,000 claimed in the subcontractor’s (Broughton’s) interim payment application (known as “(IA)12”). This was the only application mentioned by Broughton in the referral although F Parkinson’s response referred to subsequent applications (IA 13 and 14) which it said superceded IA 12. The subcontract provided for notices to be served by post, email or fax, with emailed notices served during business hours deemed to be received on the same day. F Parkinson had not issued a pay less notice in relation to IA 12, but said in its response that this did not matter because it had issued pay less notices in relation to IA 13 and 14. Both had been served by letter, but the IA 14 pay less notice had also been served by email. Although F Parkinson included the relevant letters and the email in its bundle of documents, it did not draw any attention in its arguments either to the fact that the IA 14 pay less notice had been served by email, nor to the fact that the email was in the bundle. This was significant because the adjudicator decided that both pay less notices sent by letter were out of time, and this was fundamental to his decision in favour of the subcontractor. The emailed version was, however, served within time. The contractor contacted the adjudicator after receiving the decision, asking why he had not referred to the email. The adjudicator said he had not spotted the email in the bundle, and also confirmed that if he had been aware of it he would have found in favour of the contractor. The contractor then argued that the adjudicator had committed a serious natural justice breach by failing to look at the documents properly and notice the email. Rejecting the contractor’s argument, the court held that overlooking the email could properly be characterised as a “procedural error” by the adjudicator. There had not been any deliberate decision by the adjudicator to disregard the document (which may have amounted to a serious natural justice breach) but rather the court said it was largely the contractor’s own fault for not drawing the existence of such an important document to the adjudicator’s attention in either its response or subsequent submissions. As the judge in the case concluded: “I accept that this may leave the defendant with a sense of injustice but that, I am afraid, is part of the rough and ready nature of the adjudication process…”. Savoye and Savoye Ltd v Spicers Limited Section 105(1) of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (as amended) (“the Act”) defines the “construction operations” which are subject to the Act. The first two limbs of the definition include the construction, alteration, repair, maintenance, extension, demolition or dismantling of: 5 Spring 2015 In Site • buildings, or structures forming, or to form, part of the land, whether permanent or not (section 105(1)(a)) and • any works forming, or to form, part of the land, including walls, roadworks,…industrial plant…(section 105(1)(b)). Other things which qualify as construction operations (such as the installation of certain fittings, site clearance, and other integral or preparatory services) are covered by Sections 105(1)(c)-(f) of the definition. The key feature of both Sections 105(1)(a) and (b) is that the relevant building, structure or works must form (or be to form) part of the land. The relatively limited case law on what this entails has been developed in the recent case of Savoye and Savoye Ltd v Spicers Ltd [2014] EWHC 4195 (TCC) in the context of the “industrial plant” component of the definition in Section 105(1)(b). The case also considers the extent to which it is correct to consider Section 105(1) as effectively establishing a dividing line between chattels and fixtures, with the Act only applying to the construction, alteration, repair and so forth of the latter. Akenhead J considered whether a conveyor system in a factory warehouse was sufficiently attached to the floor to conclude that it formed part of the land (and whether its installation was a construction operation and the adjudication provisions of the Act hence applied to the dispute). He noted that, whilst the principles of real property law regarding fixtures casts useful light on the test for coming within s 105(1), “…it is not some sort of pre-condition that the test or threshold of "forming part of the land" can only be "passed" if the item of work etc is a fixture as understood in the law of real property”. This is supported by the language in s 105, including reference to non-permanent buildings or structures and industrial plant. Whether something forms or is to form part of land is ultimately a question of fact and this involves fact and degree. Akenhead J gave the following useful guidance on establishing whether the criteria in s 105(1) are made out: • objects which rest on land under their own weight without mechanical or similar fixings can still be a fixture or form part of the land. It is primarily a question of fact and degree; • it is essential to have regard to the objective purpose of an object or installation being in or on the land or building to establish whether it forms part of the land. If an object or system was installed to enhance the value and utility of the premises to and in which it was annexed, that is a strong pointer to it forming part of the land; • where machinery or equipment is placed or installed on land or within buildings, particularly if it is all part of one system, one should have regard to the installation as a whole, rather than each individual element on its own. The fact that even some substantial and heavy pieces are more readily removable than others is not in itself determinative that the installation as a whole does not form part of the land. Machinery and plant can be structures, works (including industrial plant) and fittings within the context of Sections 105(1)(a) to (c) of the Act; • simply because something is installed in a building or structure does not mean that it necessarily becomes a fixture or part of the land. Heating and lighting systems would form part of the land but nobody “thinking rationally” would say the same of the installation of a standing refrigerator or washing machine; and 6 Spring 2015 In Site • the fixing with screws and bolts of an object to or within a building or structure is a strong pointer to the object becoming a fixture and part of the land but it is not absolutely determinative, and ease of removability of the object or installation in question is a factor. The fact that the fixing can not be removed save by destroying or seriously damaging it or the attachment is a pointer to what it is attaching being part of the land. Authors: Kevin Greene kevin.greene@klgates.com +44.(0)20.7360.8188 Mike Stewart mike.stewart@klgates.com +44.(0)20.7360.8141 Inga Hall inga.hall@klgates.com +44.(0)20.7360.8137 Mary Lindsay mary.lindsay@klgates.com +44.(0).20.7360.8224 Daniel Clyne daniel.clyne@klgates.com +44.(0).20.7360.6441 Anchorage Austin Beijing Berlin Boston Brisbane Brussels Charleston Charlotte Chicago Dallas Doha Dubai Fort Worth Frankfurt Harrisburg Hong Kong Houston London Los Angeles Melbourne Miami Milan Moscow Newark New York Orange County Palo Alto Paris Perth Pittsburgh Portland Raleigh Research Triangle Park San Francisco São Paulo Seattle Seoul Shanghai Singapore Spokane Sydney Taipei Tokyo Warsaw Washington, D.C. Wilmington K&L Gates comprises more than 2,000 lawyers globally who practice in fully integrated offices located on five continents. The firm represents leading multinational corporations, growth and middle-market companies, capital markets participants and entrepreneurs in every major industry group as well as public sector entities, educational institutions, philanthropic organizations and individuals. For more information about K&L Gates or its locations, practices and registrations, visit www.klgates.com. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. © 2015 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved. 7