Repr i nt ed

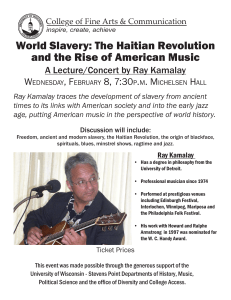

advertisement

R epr i n t edwi t hper mi s s i onf r om t h eAs s oc i at i onofCor por at eCou n s el . © 2011,t h eAs s oc i at i onofCor por at eCou n s el .Al lr i gh t sr es er v ed. www. ac c . c om. DVLDQEULHILQJV in protecting IP and preventing its improper dissemination. The overarching challenge is twofold: how to identify and mitigate the greatest areas of IP risk, and how to decide who will be responsible for implementing and managing IP risk mitigation measures. Simply leaving the task to “legal” will result in a less effective and comprehensive IP Plan. If IP is approached from solely a legal perspective — the typical approach — the conventional tools that will be relied upon are registration (e.g., patents, copyrights, trademarks, domain names) and the use of contracts (e.g., nondisclosure agreements, noncompetition agreements, licenses). These are key tools, without question. They are not, however, the only items organizations should have in their IP risk mitigation toolbox. While essential, registration and use of contracts are limited in what they can impact. Organizations that rely solely on these tools limit their options. For example, legal remedies for infringement of registered IP, or through enforcement of contracts, are generally available only after the IP has left the building. Adding tools can help construct a stronger, more effective framework to help prevent the misappropriation of IP, literally shutting the door so that IP cannot be taken from the building. The plan will take different forms for different organizations, but all plans are driven by identifying the types and sources of IP risk present in each of the organization’s operational or functional areas. For example, manufacturing companies have a few risk classes. These include counterfeiting of products (the passing off by one company of unauthorized copies of products made by another company); the outright theft of IP (the misappropriation of proprietary information that allows a company to manufacture products that are identical to what the competing company produces or to use processes that are the same or similar to processes used by the competitor); or more subtle takings of IP (copying of information that would allow one company to close any technology or quality gap with the competition). The latter type of misappropriation is more common among former joint venture partners or licensees, who have their own trade name and may use the technology gleaned (or taken) from the former partner to improve their offerings under their own brand name. An engineered approach that involves planning, and assessment or measurement to reduce IP loss exposure builds on the toolbox basics. This approach relies on the use of available tools to assess and plan on how processes flow — or fail — and how networks connect or collapse. The engineered approach involves proactive, preventive measures and process improvements. Processes that are not working well are reworked, fixed or improved; or an entirely new process is developed. $)UDPLQJ7RRO One approach to assess IP risk is to use a new tool — an IP Risk Mitigation Plan. In its fundamental form, the plan looks like this (Table 1): 2SHUDWLRQDORU )XQFWLRQDO$UHD ,GHQWLILHG 5LVNV 0LWLJDWLQJ$FWLYLWLHV 6SHFLILF7RROV 6WUDWHJLHV 5HVRXUFHV 5HVSRQVLEOH 3DUW\ Table 1 DVSHFLDOVXSSOHPHQWRI$&&'RFNHW Launching a cross-function dialogue to develop the IP plan not only builds company-wide awareness of the dangers of inadvertent disclosure; it provides stakeholders with insights that allow them to develop practical solutions to reducing risk. For example, a well-regarded multinational several years ago established a joint venture in China with a local partner to manufacture products in China. The Chinese partner was well known in DVLDQEULHILQJV the industry and competed in China with the multinational on similar products outside the scope of their joint venture. Both partners seconded employees to manage and operate the joint venture. The multinational provided the joint venture employees access to its IT network so that it could easily communicate with its expat employees on a secure network and exchange relevant manufacturing information with the joint venture. Years later, the multinational managers realized that by providing access to their “secure” network, they inadvertently also provided access to the employees seconded by their joint venture partner to their engineering database. The database contained extremely sensitive product specifications and technical information for all the multinational’s products, not just the products within the scope of the joint venture. Once on the “secure” network, users could dig into all databases on the network. A cross-functional dialogue between the information technology team, the lawyers, and engineering and operations would have identified the network access as a risk to be mitigated. 7KLVFURVVIXQFWLRQDODZDUHQHVV SDYHVWKHZD\WRZKDWLV SHUKDSVWKHPRVWLPSRUWDQW VWHSLQGHYHORSLQJDQ,3ULVN PLWLJDWLRQSODQNQRZLQJ ZKHUHULVNVDUHORFDWHG • • • • research and development; production (including quality control); distribution; information technology (i.e., system wide, does the architecture of the IT system create or mitigate risk of IP loss?); and • human resources (i.e., what policies/procedures can the HR function adopt to support IP protection, such as background checks or an IT access audit prior to employee departure interview). This cross-functional awareness paves the way to what is perhaps the most important step in developing an IP risk mitigation plan: knowing where risks are located. 6WDUWLQJ3RLQW:KHUH$UHWKH5LVNV" The in-house lawyer of this hypothetical chemical company might decide that production represents the greatest risk of IP theft, because most of the products currently being Pinpointing the source of risk as it relates to different functional areas is the key to developing a plan and a set of tools to mitigate IP loss risk. This requires a thorough evaluation of the company’s greatest exposure (Table 2). The IP Plan and the role of in-house counsel in developing and implementing the plan will vary at each company, but the IP Plan framework will apply to any type of company. To apply the framework, companies should first consider the key operational and functional areas of the organization. In a chemical production company, those areas might be: 2SHUDWLRQDORU )XQFWLRQDO$UHD ,GHQWLILHG 5LVNV 0LWLJDWLQJ$FWLYLWLHV DQG6WUDWHJLHV 6SHFLILF7RROV 5HVRXUFHV 5HVSRQVLEOH 3DUW\ (FRPPHUFH&RPSDQ\ 6RIWZDUH'HYHORSPHQW 0DQXIDFWXUHU(QJLQHHULQJ 7KHIWRIWHFKQLFDOGUDZLQJV ZLWKSURGXFWVSHFVDQG PDQXIDFWXULQJLQVWUXFWLRQV Table 2 'LVFORVXUHRINQRZ KRZDQGFRQILGHQWLDO LQIRUPDWLRQUHJDUGLQJ SURSULHWDU\SURFHVVHV $VVRFLDWLRQRI&RUSRUDWH&RXQVHO DVLDQEULHILQJV IP rights in proprietary materials and software code. So, in addition to conducting due diligence for potential outsourcing firms, the plan would include exploring with the technology team how to segment development so that no one developer handles enough segments to present an IP risk to the overall development project. Multinational companies require an expanded focus on IP risk, as different national IP laws may not provide the same or even sufficient IP protection. Under such circumstances, the IP plan may ultimately include a recommendation to avoid conducting technology-sensitive business in a particular country because the IP protection climate is unsettled and the risk too high. Most multinational companies’ IP plans will include developing a multinational network of resources such as investigators and legal counsel who know the relevant IP laws in their respective countries and have had demonstrated success in seeking enforcement of the laws. 0LWLJDWLQJ$FWLYLWLHVDQG6WUDWHJLHVWR $GGUHVV5LVNV made have been in production so long they are no longer subject to patent protection, but do incorporate trade-secret information related to product processes. This conclusion might result in a decision to explore new safeguards for access to and monitoring of the product “recipes.” Identifying risks then leads to selecting the right tool or strategy to mitigate the risk. For example, in-house counsel who decides that registering patents is the best way to protect company IP in China might open the company up to risk by simply relying on contractual measures that require other parties (suppliers, etc.) dealing with the IP to covenant not to use it or not to register it under their own name. Too often, such contractual “protection” alone buys little more than the ability to bring a lawsuit when the covenants are broken. A better strategy would be conducting ample due diligence before entering into the relationship and then setting up and managing the third-party relationships so their access to the proprietary information is restricted, limited and subject to audit. In certain instances, applying the framework will allow representative IP risks to be identified as key operational and functional areas are identified. For example, in a manufacturing company, the key functional areas and representative risks might be: • supply chain/purchasing: What type of product specifications, tolerances, etc., are routinely shared with suppliers or contract manufacturers? • plant management: Do plant floor employees have unmonitored access to proprietary information (complete bills of material, product drawings, etc.)? • human resources: How are new local employees who will have access to sensitive information recruited, vetted, trained and retained? • sales and marketing: To what degree do sales representatives have proprietary information regarding product manufacturing processes, product specifications, identity of key suppliers, etc.? In most instances, the best agreement is the one that you never have to enforce because you have built a solid business relationship with the other party that the party values and respects (and dares not break). Here’s how an IP risk mitigation plan might be structured for the engineering area where the IP cannot be protected through registration (Table 3): 'HYHORSLQJ6SHFLILF7RROVDQG5HVRXUFHV By contrast, the in-house attorney developing a proactive IP plan for an ecommerce business might focus primarily on risks presented by outside software developers to DVSHFLDOVXSSOHPHQWRI$&&'RFNHW This list is not comprehensive; each company will want every business unit to brainstorm to ensure a plan recognizes and DVLDQEULHILQJV $OORFDWLQJ5HVSRQVLELOLW\ responds to key risks. That overview then leads to a more detailed and specific plan identifying tools and resources. The final step is to allocate responsibility across the organization. Using again the example of risks associated with engineering activities in a manufacturing business, the relevant stakeholders for implementation might be (Table 5): Specifics are essential to assign responsibility for implementation of these strategies to responsible departments and team members. Again, continuing with the engineering example above, we might list some specific tools such as (Table 4): 2SHUDWLRQDORU )XQFWLRQDO$UHD (QJLQHHULQJ Involving other relevant functional areas fosters ownership of IP protection across the organization, which is a ,GHQWLILHG5LVNV 0LWLJDWLQJ$FWLYLWLHVDQG6WUDWHJLHV 'LVFORVXUHRINQRZKRZDQGFRQILGHQWLDOLQ IRUPDWLRQDQGGDWDUHJDUGLQJSURFHVVHV 8QDXWKRUL]HGDFFHVVWRWHFKQLFDOGUDZLQJV 8VHSURSHUFRQILGHQWLDOLW\DQGLQQRYDWLRQDVVLJQ PHQWDJUHHPHQWVZLWKHPSOR\HHVDQGWKLUGSDUWLHV (VWDEOLVKDFRGHRIFRQGXFWDQGRUJXLGH OLQHVZLWKGLVFLSOLQDU\PHDVXUHVFRPSO\LQJ ZLWKORFDOODZWUHDWWKHKDQGOLQJRIFRQIL GHQWLDOLQIRUPDWLRQDVDQHWKLFDOLVVXH 7UDLQHPSOR\HHVLQWKHSURSHUKDQGOLQJRI SURSULHWDU\DQGFRQILGHQWLDOLQIRUPDWLRQ 8VHSURSHUVLJQDJHDQGSK\VLFDOEDUULHUVWRVKLHOG DQGRUUHVWULFWDFFHVVWRSURSULHWDU\LQIRUPDWLRQ Table 3 )XQFWLRQDO$UHD (QJLQHHULQJ 0LWLJDWLQJ$FWLYLWLHVDQG6WUDWHJLHV 6SHFLILF7RROV5HVRXUFHV 8VHSURSHUFRQILGHQWLDOLW\DQGLQQRYDWLRQDVVLJQ PHQWDJUHHPHQWVZLWKHPSOR\HHVDQGWKLUGSDUWLHV (QJLQHHULQJPDQDJHUVWRSURYLGHWUDLQLQJIRUDOOVWDII (VWDEOLVKDFRGHRIFRQGXFWDQGRUJXLGH OLQHVZLWKGLVFLSOLQDU\PHDVXUHVFRPSO\LQJ ZLWKORFDOODZWUHDWWKHKDQGOLQJRIFRQIL GHQWLDOLQIRUPDWLRQDVDQHWKLFDOLVVXH 'HYHORSOHYHOVRUFDWHJRULHVRIFRQILGHQWLDOLW\DQGRU VHQVLWLYLW\²HJ35235,(7$5<35235,(7$5< $1'+,*+/<&21),'(17,$/75$'(6(&5(7 7UDLQHPSOR\HHVLQWKHSURSHUKDQGOLQJRISUR SULHWDU\DQGFRQILGHQWLDOLQIRUPDWLRQ 8VHVRIWZDUHDQGIORRUSURFHGXUHVWRVHJ UHJDWHFULWLFDOSURFHVVHVDQGNQRZKRZDF FRUGLQJWRFDWHJRULHVRIFRQILGHQWLDOLW\ 8VHSURSHUVLJQDJHDQGSK\VLFDOEDUULHUVWRVKLHOG DQGRUUHVWULFWDFFHVVWRSURSULHWDU\LQIRUPDWLRQ 0RQLWRUDQGUHJXODWHDFFHVVWRVHQVLWLYHLQ IRUPDWLRQDQGGDWDXVLQJWKHXQLTXH,'VRI HPSOR\HHV³ILQJHUSULQWNH\SDGHQWU\WRVHFXUH DUHDVDQG,'DFFHVVFRGHVIRUFRPSXWHUV Table 4 $VVRFLDWLRQRI&RUSRUDWH&RXQVHO DVLDQEULHILQJV critical part of a successful IP risk management plan. 6SHFLILF7RROV5HVRXUFHV (QJLQHHULQJ <RXU$SSURDFK <LHOGV%HQHILWV 5HVSRQVLEOH3DUW\ &DQGLGDWHVPLJKWLQFOXGH /HJDO (QJLQHHULQJ 4XDOLW\DQG,7 +5²HPSOR\HHLQFHQWLYHV (QJLQHHULQJPDQDJHUVSURYLGHWUDLQLQJIRUDOOVWDII An engineered approach to an integrated IP risk mitigation plan provides several benefits: • Assessing true risk means 'HYHORSOHYHOVRUFDWHJRULHVRIFRQILGHQWLDOLW\DQG companies are more likely RUVHQVLWLYLW\HJ35235,(7$5<35235,(7$5<$1' to identify and use the +,*+/<&21),'(17,$/75$'(6(&5(7 correct strategy or tool to mitigate the risk. • Taking a holistic view 8VHVRIWZDUHDQGIORRUSURFHGXUHVWRVHJUHJDWHFULWLFDOSUR of IP protection: Your FHVVHVDQGNQRZKRZDFFRUGLQJWRFDWHJRULHVRIFRQILGHQWLDOLW\ available range of tools to address and mitigate risk is significantly broader than 0RQLWRUDQGUHJXODWHDFFHVVWRVHQVLWLYHLQIRUPDWLRQDQG you might initially think GDWDXVLQJWKHXQLTXH,'VRIHPSOR\HHV³ILQJHUSULQWNH\SDG if you do not approach IP HQWU\WRVHFXUHDUHDVDQG,'DFFHVVFRGHVIRUFRPSXWHUV protection from a purely legal perspective — instead of thinking contracts Table 5 and registration, you may develop ideas about limiting physical access to the workshop, segregating difNotes 1. PRC courts can issue policy statements independently without the ferent steps in the production process or whether visitors need for a case or controversy to be presented; and from time to are allowed to bring their cell phones into your facility. time, high-level courts will issue these interpretations which are then • Your non-legal colleagues can relate, contribute to binding on courts deciding cases within that jurisdiction. 2. See Article 11 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on and support the aims of the plan more actively and Some Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil profitably than if it remains an initiative of the legal Cases involving Unfair Competition, issued by the Supreme People’s department. An initiative in any organization will Court of the People’s Republic of China on January 12, 2007, and effective as of February 1, 2007. be more effective when other departments and func3. Sean Major is executive vice president, general counsel and secretary tional areas perceive “ownership” in the process. of Joy Global, Inc. • If your IP does become compromised, your company 4. Amy Sommers is a Shanghai-based partner in the firm of Squire Saunders and Dempsey whose involvement in China dates back 25 years. will still be in a better position than without the plan: You will have signed non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) with potential suppliers; you will have evidence of notification that information provided is proprietary; you can demonstrate that you limited access to it — all these steps will provide evidence to support your claims should you choose to pursue legal remedies against the party wrongfully appropriating your IP. DE DVSHFLDOVXSSOHPHQWRI$&&'RFNHW ;VMXI3R =SYLEZIEWXSV]SXLIVW[ERXXSLIEVMX You might not think so, but what you have to say is important. ACC is by in-house counsel, for in-house counsel. There are thousands of other members just like you; important matters that you learn, experience, and worry about are important to them as well. Author an article for the ACC Docket to expand the thinking and continue the dialog. It also doesn’t hurt to be able to say you’re a published author! By in-house counsel, for in-house counsel.® 8EOIXLIRI\XWXIT'SRXEGX/MQ,S[EVH IHMXSVMRGLMIJXSTVSTSWI]SYVEVXMGPI LS[EVH$EGGGSQSV\